- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Custom Article Title: John Rickard reviews 'Divas: Mathilde Marchesi and her pupils' by Roger Neill

- Custom Highlight Text:

Finding the right teacher is always a challenge for young singers, and the relationship between student and teacher can see the formation of a lifelong bond. By the same ...

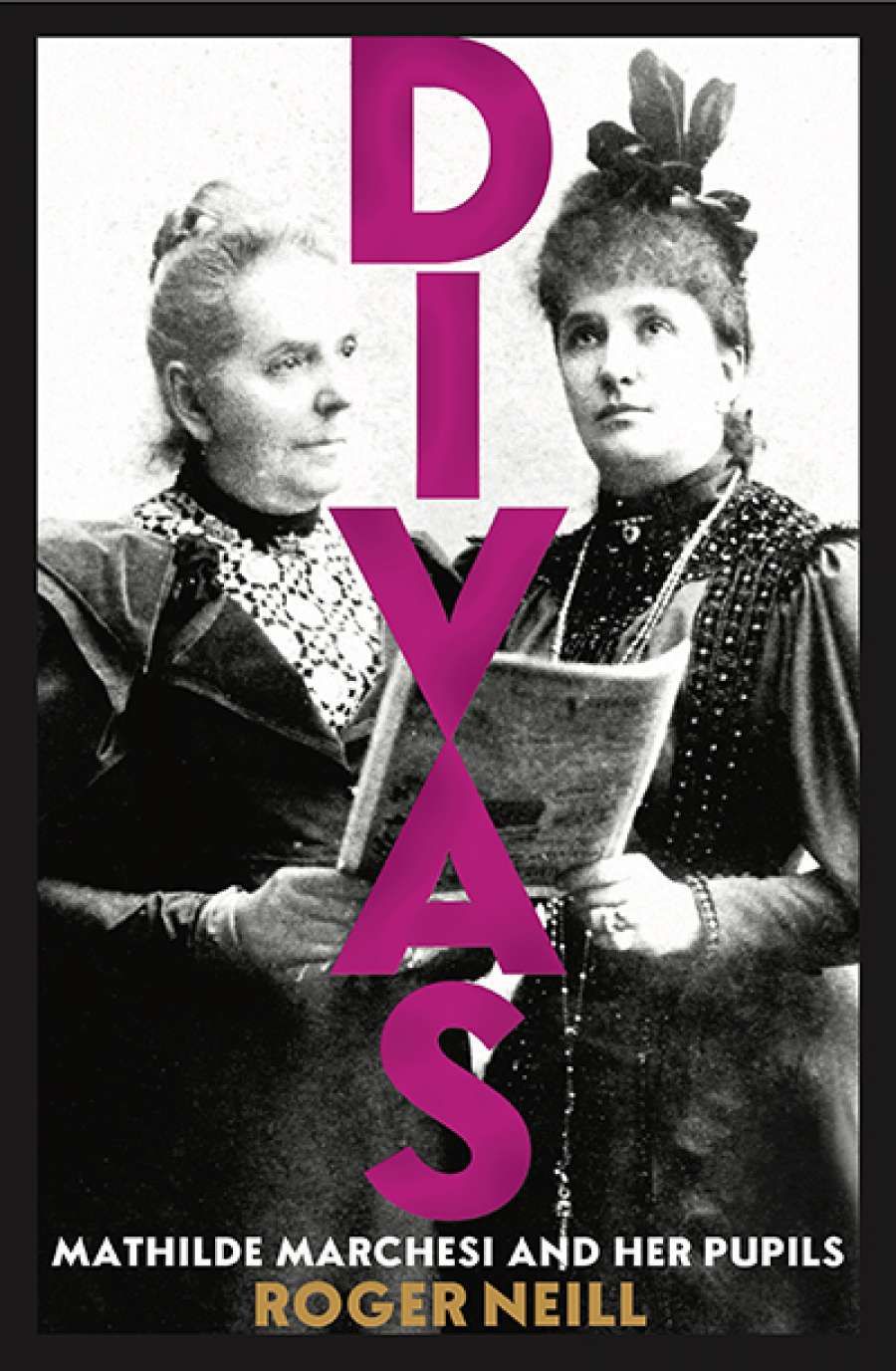

- Book 1 Title: Divas

- Book 1 Subtitle: Mathilde Marchesi and her pupils

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth $69.99 hb, 436 pp, 9781742235240

Nor was it just singing that Marchesi taught. She gradually developed a program designed to prepare the student for a career on stage or concert platform. ‘Literature, declamation, history, harmony, the history of music, the French, German and Italian languages – all these branches of learning must be thoroughly studied,’ she wrote in one of her texts. She also advised on diet, emphasising the importance of breakfast, and told her students to refrain from bicycling, rowing, dancing, long walks, and reading late at night. She was well placed to help deserving students launch their careers, and she invited agents, impresarios, composers, and opera house managers to her regular student concerts. The singer’s image was also important: many of her students, like Melba, had a suitable name created for them, usually one with a vaguely Italian sound to it.

Roger Neill understandably seeks out every Australian connection, starting with the Austrian Elise Wiedermann, who had been a Marchesi student and had a quite distinguished operatic career before her engagement to Carl Pinschof. The businessman had visited Australia and seen opportunities in go-ahead Melbourne, so that was where they settled. Wiedermann, who taught singing and became involved in the local cultural scene, gave Nellie Mitchell a letter of introduction to her old teacher in Paris. Many aspiring Australasian singers followed Melba in making the pilgrimage to Madame Marchesi.

Much has been made of the Marchesi ‘method’, not least by herself in her publications. At a time when it was common for female singers, having débuted as young as seventeen, to burn out before they reached forty, Marchesi trained her students in the art of preserving their voices. Although she insisted that a student must have three lessons a week, each was usually no more than twenty minutes. Marchesi believed, rather against the medical evidence, that the female voice had three, not two, registers – the chest, the medium, and the head. Marchesi’s students, in the bel canto tradition, were notable for their ‘ravishing piano head-notes’. The advent of Wagner, with the increasingly demanding roles he created, particularly for sopranos, was problematic for Marchesi. In their preparation of arias, her students were allowed to study Elsa in Lohengrin, Eva in Die Meistersinger, Elizabeth in Tannhäuser and Senta in Der fliegende Holländer, but Brünnhilde and Isolde were definitely off limits. Against her teacher’s advice, Melba made one attempt at Brünnhilde in Siegfried, which was a disaster.

Matilde Marchesi, 1895 (photograph by Wilhelm Benque (1843–1903), Wikimedia Commons)The challenge for a book such as this is to maintain a narrative thread; at times this does seem to get lost in a succession of mini-biographies of divas, including some who had hardly any exposure to Marchesi’s ‘method’. Madame’s story, of course, should provide the continuity, but here sources are sparse, and Neill is very dependent on the memoirs of Marchesi and her daughter Blanche. A chapter on the ‘method’ comes at the end of the book, almost as an afterthought, and although appendices record the dispersal of her influence through later generations of teachers, there is limited evaluation of this legacy. And there is one obvious question which Neill never addresses: why did Marchesi teach only women? Was this simply reflecting a nineteenth-century convention that it was not appropriate for a woman to be instructing a man? And if so, when did that begin to change? Neill provides only sketchy historical context.

Matilde Marchesi, 1895 (photograph by Wilhelm Benque (1843–1903), Wikimedia Commons)The challenge for a book such as this is to maintain a narrative thread; at times this does seem to get lost in a succession of mini-biographies of divas, including some who had hardly any exposure to Marchesi’s ‘method’. Madame’s story, of course, should provide the continuity, but here sources are sparse, and Neill is very dependent on the memoirs of Marchesi and her daughter Blanche. A chapter on the ‘method’ comes at the end of the book, almost as an afterthought, and although appendices record the dispersal of her influence through later generations of teachers, there is limited evaluation of this legacy. And there is one obvious question which Neill never addresses: why did Marchesi teach only women? Was this simply reflecting a nineteenth-century convention that it was not appropriate for a woman to be instructing a man? And if so, when did that begin to change? Neill provides only sketchy historical context.

Divas: Mathilde Marchesi and her pupils is a valuable resource, but documentation is curiously intermittent, and there is no suggestion of it being provided on a website.

Comments powered by CComment