- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

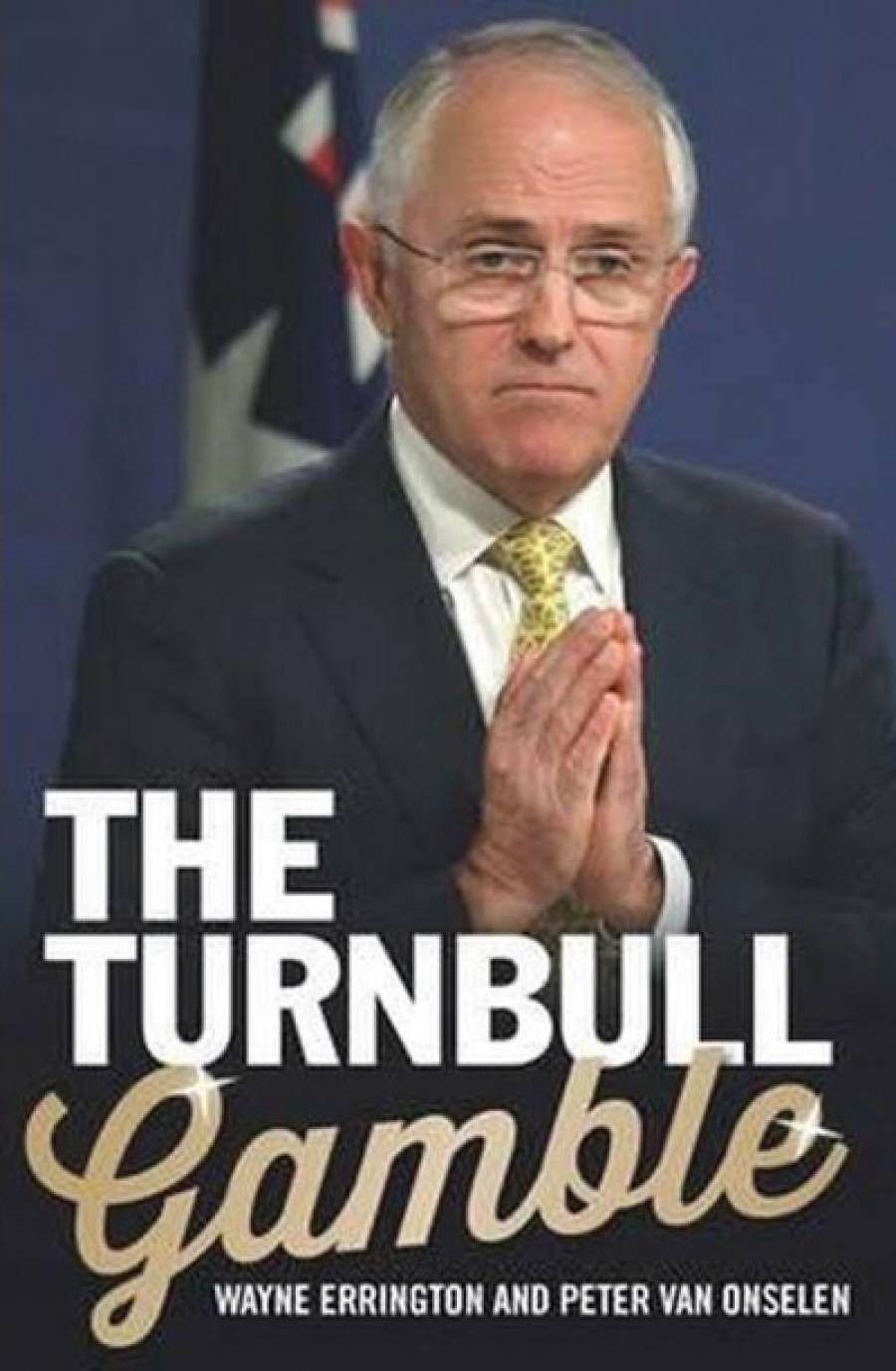

- Custom Article Title: Lucas Grainger-Brown reviews 'The Turnbull Gamble' by Wayne Errington and Peter van Onselen

- Custom Highlight Text:

After he crossed the Rubicon, Julius Caesar marched on Rome and imposed an authoritarian rule that would alter history. The way in which Australia embraced ...

- Book 1 Title: The Turnbull Gamble

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Publishing, $29.99 pb, 207 pp, 9780522870732

Errington and van Onselen have provided cuttingly honest leadership portraits of John Howard and Tony Abbott in their first two books: John Winston Howard: The definitive biography (2007) and Battleground: Why the Liberal Party shirtfronted Tony Abbott (2015). Their third consecutive study of a Liberal prime minister is, however, hampered by the ephemerality of Turnbull as a leader. The leadership portion of this book begins with the promising concept of ‘transaction costs’ associated with changing leader. But what might have been an interesting theorisation of the increasingly short tenure enjoyed by Australian prime ministers quickly devolves into the much less illuminating, ‘what if Bad Malcolm hadn’t really changed?’.

The yardstick for Bad Malcolm is a lionised incarnation of John Howard, touchstone for good Liberal leadership (despite incubating many of the modern party’s flaws). Errington and van Onselen layer superficial arguments about Turnbull’s personality using the headlines from his parliamentary career: hostilities with Brendan Nelson; Godwin Grech’s ‘Utegate’ scandal; Kevin Rudd’s Emissions Trading Scheme. Through these lenses, Turnbull is diagnosed as a narcissist, referencing, in an overreach, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Moving on from pop psychology, the authors then affix to Turnbull the epithet ‘bower bird’. Defining Malcolm’s spirit animal as a hoarder of political ‘shiny objects’ is an indirect criticism of his unprincipled inconstancy. This half-hearted caricature is inferior to those of the authors’ peers. Paddy Manning and Annabel Crabb have both produced excellent biographies of Turnbull.

The authors’ insider knowledge is impeccable, often rendering details that escape the headlines. Revelations such as Bill Shorten facing down a left-wing leadership plot in early 2016, and Scott Morrison’s deep involvement in ousting Abbott, even conspiring with Turnbull in the February 2015 spill motion, bolster the engaging and substantive election coverage.

The second half of this book might be the most immediate release of a scholarly electoral study in Australian political history. This section was drafted while the campaign unfolded. Errington and van Onselen provide a lucid and detailed analysis of the campaign strategies, tactics, twists, and turns. Theirs is a welcome corrective to animated election-night ‘crushers’ and parliamentarian ‘ejection seats’. Careful scrutiny demonstrates the degree to which narrative overtook events during and especially after polling day. Arithmetically, the Opposition could never have prevailed in the twenty House of Representatives contests it needed to oust the government. The value of this history will likely grow in time as an acid test for retrospective storylines invited by future political happenings.

Despite this dividend, the conclusions reached by The Turnbull Gamble reinforce that it is an odd composition about an indecipherable politician. Errington and van Onselen consider the Liberal Party’s gamble on Turnbull a success based on electoral victory, and grade Turnbull’s disastrous double dissolution a failure. Both these propositions are self-evident and do not warrant the 180-odd pages separating question and answer. The animus of this book is also strangely detached from reality. The term gamble implies a measure of choice, and the uncharted heights of incompetency towards which the Abbott government soared left his party bound to throw in with a man many of its members distrusted.

Malcolm Turnbull (Wikimedia Commons)Although they range expansively over most factors affecting the Australian political milieu, Errington and van Onselen inexplicably focus on esoteric and irrelevant patches of our rupturing electoral landscape. In an election remarkable for the success of minor parties, they conspicuously avoid the global tectonic shifts roiling the West. Laying out the emergent stakes for democracy, American author Fareed Zakaria wrote an excellent article on populism in the August 2016 edition of Foreign Affairs. In it he dissected the cultural wave of reaction against immigration, progressivism, and social élites. Canvassing the countries of the globe, from Japan to Canada to Greece, he concluded that ‘there is no substitute for enlightened leadership’ in countering the mobilisation of populist extremists.

Malcolm Turnbull (Wikimedia Commons)Although they range expansively over most factors affecting the Australian political milieu, Errington and van Onselen inexplicably focus on esoteric and irrelevant patches of our rupturing electoral landscape. In an election remarkable for the success of minor parties, they conspicuously avoid the global tectonic shifts roiling the West. Laying out the emergent stakes for democracy, American author Fareed Zakaria wrote an excellent article on populism in the August 2016 edition of Foreign Affairs. In it he dissected the cultural wave of reaction against immigration, progressivism, and social élites. Canvassing the countries of the globe, from Japan to Canada to Greece, he concluded that ‘there is no substitute for enlightened leadership’ in countering the mobilisation of populist extremists.

Here is the real ‘transaction cost’ Australia must pay for Malcolm Turnbull. As the authors observe, he cannot be a benevolent autocrat nor remake the government in his image. A morally ambivalent careerist cannot conquer in the name of good sense during an epoch primed for demagogues. Although Howard is Turnbull’s natural analogue, the Coalition has drifted away from the party that his predecessor led. Conservative institutionalism, reactionary radicalism, Howard’s nationalism, Turnbull’s vague liberal neo-liberalism, and One Nation’s ethnocentrism are vying for prominence in the government’s agenda. Increasingly, the Coalition is coming to resemble US Republicans and UK Conservatives, both of whom refuse to submit to the imperatives of good government, much less rise to the pressing problems of this age.

Andrew P. Street, also celebrating the Turnbull government’s anniversary by rushing into print, tries to make light of this farcical turn in his sardonic The Curious Story of Malcolm Turnbull: The incredible shrinking man in the top hat (Allen & Unwin, $29.99 pb, 356 pp, 9781760294885) Even Street’s single-malt wit cannot soften the distastefulness of an electorally victorious leader denied a legislative program by his own party. Characters that Street skewers are all carried over from his earlier page-turner, The Short and Excruciatingly Embarrassing Reign of Captain Abbott (2015); their antics are too familiar. The Liberal Party’s real gamble is preventing Turnbull from realising the expectations that made him, for a few short weeks, one of Australia’s most popular prime ministers. Holding the nation hostage will only increase voter disillusionment. Beside which, 2016 election tactics and Turnbull’s peccadillos pale in significance.

The Turnbull Gamble provides a mimesis of Turnbull: clever without cutting through; bleeding over minor endeavours; most enlightening in its omissions. Ironically, a throwaway idiom that anoints Turnbull the Pyrrhus of Australian politics inadvertently delivers the authors’ best portent of his leadership. Pyrrhus was a rich, powerful freelancer; he won his eponymous battles in southern Italy only to come undone through inept entanglement in the thorny affairs of lesser powers; his vassals turned on him and the Romans expelled the fallen trespasser. With luck, Malcolm Turnbull’s political fate need not facilitate the rise of a more capable and less liberal Caesar.

The Turnbull Gamble provides a mimesis of Turnbull: clever without cutting through; bleeding over minor endeavours; most enlightening in its omissions. Ironically, a throwaway idiom that anoints Turnbull the Pyrrhus of Australian politics inadvertently delivers the authors’ best portent of his leadership. Pyrrhus was a rich, powerful freelancer; he won his eponymous battles in southern Italy only to come undone through inept entanglement in the thorny affairs of lesser powers; his vassals turned on him and the Romans expelled the fallen trespasser. With luck, Malcolm Turnbull’s political fate need not facilitate the rise of a more capable and less liberal Caesar.

Comments powered by CComment