- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

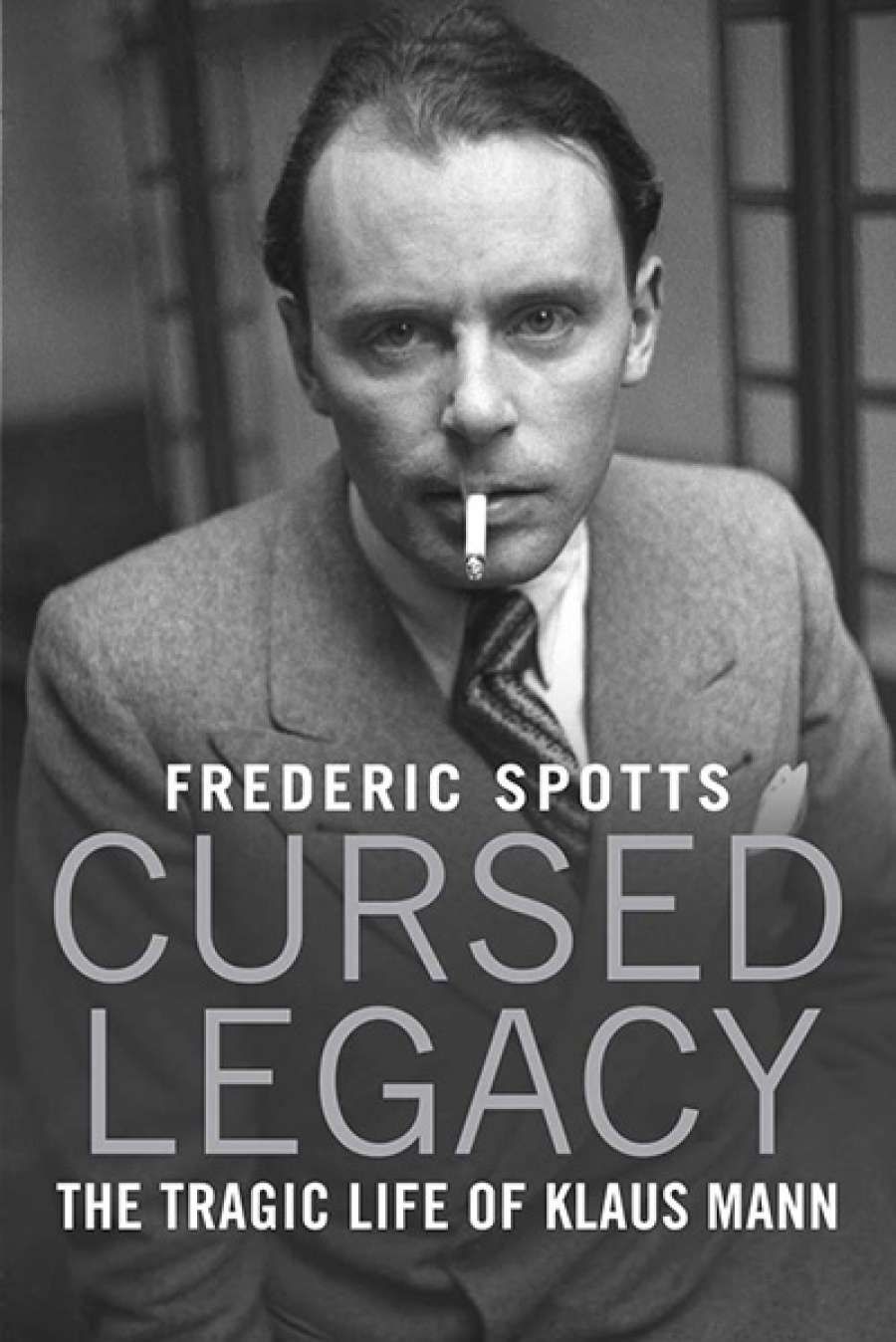

- Custom Article Title: Evelyn Juers reviews 'Cursed Legacy: The Tragic Life of Klaus Mann' by Frederic Spotts

- Custom Highlight Text:

In ‘The Art of Biography’, Virginia Woolf insists that this ‘is the most restricted of all the arts’ and that even if many biographies are written, few survive. But somehow ...

- Book 1 Title: Cursed Legacy

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Tragic Life of Klaus Mann

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press (Footprint), $75 hb, 338 pp, 9780300218008

Klaus was especially close to his mother and sister Erika, but within their difficult family dynamics he showed solidarity with all his siblings. Unlike his father’s lifelong battle with homoerotic desire, Klaus acknowledged his own homosexuality from an early age. He also gave free rein to his fascination with suicide, which (Spotts proposes) must have begun innocently, as part of a ‘long tradition of German youth’, but soon became ‘morbid’, making him a dedicated ‘voyeur of death’.

With Erika he goes on teenage escapades. Their parents think they are on a cheerful walking tour of Thüringen. Instead, they head straight to the ‘homosexual heaven’ of Berlin. While Erika is drawn to political theatre, Klaus decides to become a writer. By the end of his teens ‘Klaus was a youth in psychological, sexual and moral turmoil.’ He speaks and writes rapidly, travels compulsively – in Europe, America, Africa, the Pacific, and the Soviet Union – and is puzzled by this innate restlessness. He often misbehaves. As a theatre critic, for example, ‘it amused him to praise nobodies ... and take the mickey out of distinguished actors’. He knows everyone. Mostly he lives in hotel rooms, governed by the rituals of packing and unpacking a clutch of photographs, typewriter, cigarettes, difficult relationships, casual sex, and drugs. His intensity arises from an overwhelming fear of loneliness and failure.

The Mann family on vacation at Hiddensee on the Baltic Sea, 1924. Left to right: Katia, Monika, Michael, Elisabeth, Thomas, Klaus, and Erika

The Mann family on vacation at Hiddensee on the Baltic Sea, 1924. Left to right: Katia, Monika, Michael, Elisabeth, Thomas, Klaus, and Erika

When Hitler came to power Klaus went into exile, where he wrote a blazing manifesto of resistance in the form of a letter to the once highly esteemed poet Gottfried Benn, who had thrown in his lot with the Nazis. Decades later, Benn confessed that Klaus Mann was right; that this young man had seen things ‘much more presciently than I did’. Both Klaus and Erika were increasingly involved in protests – they commissioned exiled writers, staged cabarets, spoke forcefully on radio, at rallies and conferences – while their father, careful not to offend his German publisher and his public, stayed silent on politics.

It was his premonition of an escalating crisis that had propelled Klaus Mann into writing Mephisto. Then Austria was annexed, Czechoslovakia sacrificed, fascism spread in Italy and Spain, the German–Soviet pact was signed, war broke out, and the French surrender triggered a massive refugee crisis in Europe. Dissent proved ineffective. With no passport and nowhere to go, Klaus fell ever deeper into despair and drugs. He sought help at various clinics. When the Manns found refuge in America, Klaus tried to start afresh by unlearning German, a language polluted by Hitler. He studied English and read voraciously; Virginia Woolf was his favourite. Ahead lay a rocky path of more failed affairs, failed ventures, failed attempts to die. But by 1942 he was writing his diary and books in English, one of the few exiled German intellectuals to master their new language.

To have some stability of place and purpose, Klaus enlisted in the American army. This brought him to the attention of the FBI, which suspected him of communist sympathies, a crime considered worse than fascism. Klaus endured a hurtful process of surveillance and character assassination. In the army, between boredom and bayonet drills, he read Proust; eventually he was assigned to the psychological warfare unit and shipped off to Europe.

Klaus Mann, Staff sergeant 5th United States Army, Italy 1944 (United States 5th Army/Wikimedia Commons)At the end of the war, as an intrepid American journalist, he returned to the bombed-out ruins of Munich and his family home and made his way to witness what had occurred at Dachau and Theresienstadt, where he met his aunt, who was barely alive. In an interview with Richard Strauss he thought the composer ‘could have lived in a land of a hundred Hitlers, providing no one bothered him personally’. He spoke with Winifred Wagner, who confirmed her admiration for Hitler, and with Karl Jaspers, who was guilt-ridden at having survived the war. Together, Klaus and Erika attended and wrote about the Nuremberg trials. Both of them believed in collective responsibility; both detested Germans. For Germans who disliked being criticised by those who had gone into exile, ‘disowning Klaus Mann was a way of disowning the past’.

Klaus Mann, Staff sergeant 5th United States Army, Italy 1944 (United States 5th Army/Wikimedia Commons)At the end of the war, as an intrepid American journalist, he returned to the bombed-out ruins of Munich and his family home and made his way to witness what had occurred at Dachau and Theresienstadt, where he met his aunt, who was barely alive. In an interview with Richard Strauss he thought the composer ‘could have lived in a land of a hundred Hitlers, providing no one bothered him personally’. He spoke with Winifred Wagner, who confirmed her admiration for Hitler, and with Karl Jaspers, who was guilt-ridden at having survived the war. Together, Klaus and Erika attended and wrote about the Nuremberg trials. Both of them believed in collective responsibility; both detested Germans. For Germans who disliked being criticised by those who had gone into exile, ‘disowning Klaus Mann was a way of disowning the past’.

In the end he was physically and emotionally exhausted. It is said he drank heavily without getting drunk and spoke in a mere whisper; one friend saw that ‘the light in his soul seems to have gone out’. When he died on 21 May 1949 in Cannes, his brother Michael was the only family member to attend the funeral. Clearly he had wanted to die, though Frederic Spotts argues that ‘biographic orthodoxy has it that he deliberately killed himself. Biographic orthodoxy errs’. Spotts believes Klaus Mann’s tragedy was his famous father, ‘who despised, tormented and humiliated him’ to the point of causing ‘depression, drug addiction and longing for death’. That is much too bold and probably only fractionally true.

It is to be hoped that Cursed Legacy will take readers back to Klaus Mann’s writings, his letters, diaries, interviews, and his portraits of Gide and Tchaikovsky, as well as the memoirs and novels. With his keen biographical instinct – not unlike Strachey’s – Klaus Mann was one of the sharpest observers of his time.

Comments powered by CComment