- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Jill Burton reviews 'Cynthia Nolan: A biography' by M.E. McGuire

- Custom Highlight Text:

When times were difficult, Cynthia Reed Nolan ‘drew the veil’. Born in Evandale in 1908, the youngest of six children, Cynthia always sought distance ...

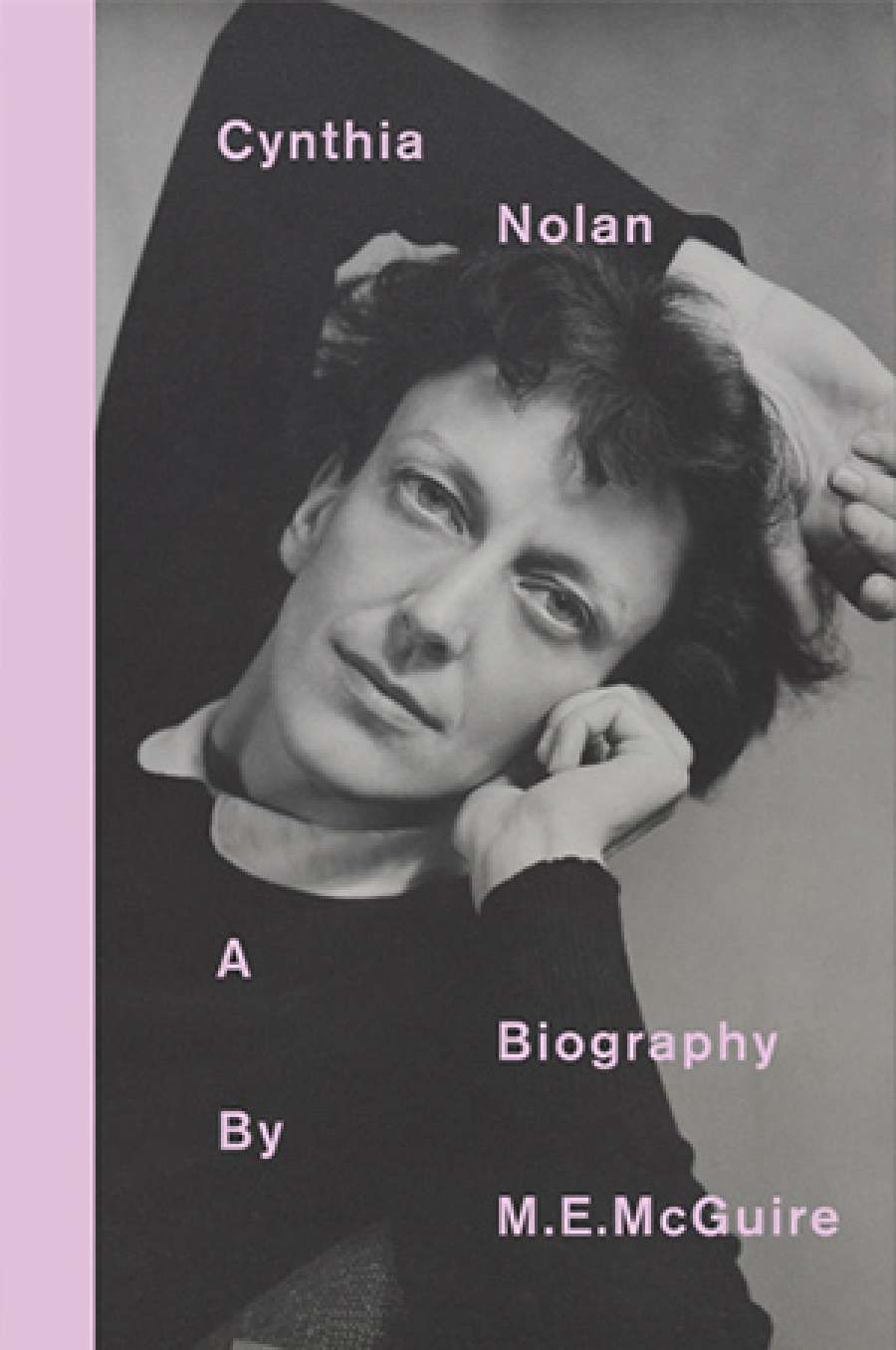

- Book 1 Title: Cynthia Nolan

- Book 1 Subtitle: A biography

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne Books $34.95 hb, 208 pp, 9781922129963

Cynthia’s life in 1930 became a mix of ‘art, sex and modern life’. Soon she was ‘setting up a modern art and design business’ to ‘give Melburnians a cosmopolitan alternative to the commercial dominance of art deco’. At her first exhibition in 1932, she was ‘congratulated on giving Australian men of real constructive genius a chance to show their work’. It was an indication of what was to become a recurring motif in her life. Her social skills and business enterprise, coupled with her ability to create an ‘air of detached calm’, tended to conceal rather than display her artistic talents. Typically understated, Cynthia’s description of her time in business in Melbourne was a ‘convalescence’.

After briefly pursuing an acting career as Miss Liese Fels in Sydney, she sailed to Los Angeles with ‘Michael’, an American film producer who was married to someone else. Redeeming this ‘mistake’, she started training as a nurse ‘in progressive America’. Unfortunately, the immigration department tracked her down at St Joseph’s near Chicago and she had to leave quickly. In London, she was accepted at St Thomas’ Hospital. Alone in 1938, facing her final examinations, Cynthia declared her daunting life ‘infinitely preferable’ to one that might have included poverty, ill health, and an unhappy marriage: she was writing, and nursing gave her a sense of purpose and interesting material. A step ahead of war, she travelled to France with friends, then on to America as the carer of a mentally ill woman. In New York, she completed a postgraduate course in psychiatric nursing before travelling home via the Caribbean and South Africa.

Pregnant, Cynthia returned to Melbourne after seven years. To protect her unborn child, she recreated herself as Mrs Knut Hansen, wife of a Danish pilot and intelligence officer who had just been ‘shot out of the sky over Romania’. No one knew the truth. John and Sunday Reed invited her to live with them at Heide, where Sidney Nolan encountered her for the first time. Not long after Jinx’s birth in 1941, and wanting ‘quiet understanding and silence’, Cynthia bought a small cottage at Wahroonga outside Sydney where she began writing Lucky Alphonse (1942), based on her overseas nursing experiences, which John published. Her second novel, Daddy Sowed a Wind, cast a bleaker light, ending with the suicide of its anti-heroine, Hyacinth. Following the novel’s publication in 1947, it was chosen as Australian Book of the Month. Its themes aroused outrage among family and friends; John and Sunday called it ‘a total disaster’. McGuire, however, claims that ‘Cynthia was a much firmer character, more worthy altogether’ than any of her characters.

Cynthia and Sidney Nolan, 1965 (National Archives of Australia)

Cynthia and Sidney Nolan, 1965 (National Archives of Australia)

The Heide household was in emotional disarray, and Sidney decided to follow the advice of Cynthia (nine years his senior) and get away. He looked her up in Sydney; soon they were married, in 1948. With Cynthia’s guidance, Sidney’s career blossomed. Their life was one of constant travel, new friendships and connections, and preparations for exhibitions. It was exhausting. During one extended road trip through the United States Cynthia developed tuberculosis. Her role as Sidney’s mainstay could no longer continue, and it was then that the Nolans’ marriage began to falter. Cynthia’s six-month hospitalisation in New York was intensely difficult for her, but a rich source of material; her memoir Open Negative (1967) showcased her perceptive writing of idiom and highlighted her discomfiture at having to live close to others.

In London, after her release from hospital, Cynthia remained in constant pain. It made for uneasiness among friends, but in the wake of her carefully orchestrated suicide in London in 1976, friends acknowledged her mental steel. ‘Let’s face it,’ Patrick White wrote in his newspaper obituary, ‘The Cynthia I Knew’, ‘Cynthia ... would have been less exhilarating, less special if she had not questioned our values, put us to the test’.

Well-behaved women seldom make history, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich argues, but Cynthia wasn’t particularly well behaved; in ensuring that Sidney Nolan realised his potential, she was perhaps unfortunate in his being so gifted an artist that he both exhausted and eclipsed her. Cynthia might have appreciated this restrained, sympathetic biography, though she would have possibly been irritated by aspects of its publication format, such as its distracting headings and chapter footnotes.

Comments powered by CComment