- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Ann-Marie Priest reviews 'Katherine Mansfield: The early years' by Gerri Kimber

- Custom Highlight Text:

Katherine Mansfield is one of those shimmering literary figures whose life looms larger than her work. This is not because her writing lacks value: Mansfield’s spiky ...

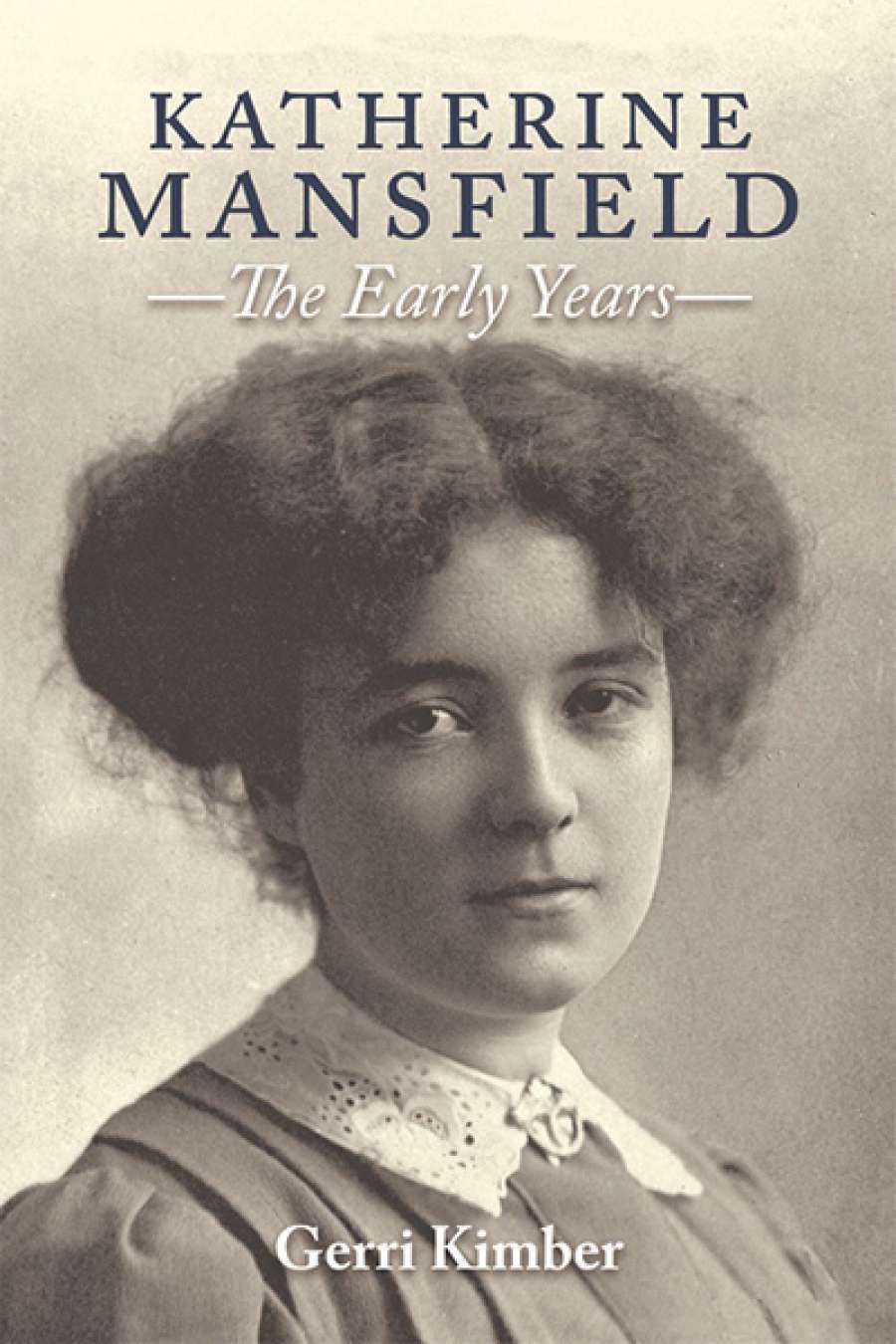

- Book 1 Title: Katherine Mansfield

- Book 1 Subtitle: The early years

- Book 1 Biblio: Edinburgh University Press (NewSouth) $69.99 hb, 304 pp, 9780748681457

In her biography of Mansfield’s early years, Gerri Kimber describes the Mantz and Murry book as ‘a rather fanciful, romantic – and, in places, inaccurate – distortion of her early life’. Kimber’s argument is that subsequent biographies – no fewer than four, in addition to numerous scholarly works – have not paid enough attention to Mansfield’s early life, and thus have not sufficiently corrected the biographical record so thoroughly smutched by Murry. Nevertheless, Kimber does not directly address any specific inaccuracies or distortions in Murry’s account, or any other. Instead, she focuses on painstakingly documenting what is known about Mansfield’s childhood and adolescence, ending her book in 1908, when the nineteen-year-old Mansfield leaves New Zealand for London for the last time. In this, Kimber draws largely on Mansfield’s own work as published in the hefty, four-volume Collected Writings, of which Kimber was the series editor (the final volume came out in 2016). These tomes contain, seemingly, every scrap of writing Mansfield ever produced, from abandoned stories and draft novels to poems, diaries, and random scribblings. Kimber’s biography is structured around those snippets that relate to Mansfield’s girlhood. As a result, the narrative – while impressively illustrated with numerous family photographs – amounts at times to little more than lengthy quotations stitched together with threads of historical context. Kimber seems curiously reluctant to draw the significance of the material she is presenting, which gives the work a desultory air. The overall effect, however, is to foreground Mansfield’s own flexible voice, which even at a young age is never less than engaging.

Kimber supplements Mansfield’s accounts of her childhood with unpublished material gathered by Mantz in 1931, when she visited New Zealand to interview Mansfield’s family and friends. Most were disapproving: until Mansfield was eleven or twelve, everyone she knew seems to have found her thoroughly unpleasant. She irritated her father, infuriated her mother, and was considered by her teachers to be ‘dull’; she of the quicksilver wit and emaciated frame was pilloried for being ‘slow and fat’. Such characterisations bring to mind other misfit Antipodean girls, including Henry Handel Richardson, who, like Mansfield, was considered to be ‘imaginative to the point of untruth’, and Christina Stead, whose father and stepmother reviled her for being ugly, fat, and passionate. In all three cases, the crux of the problem seems to have been the lack of a becoming girlish sweetness and malleability.

Katherine Mansfield, 1917 (National Portrait Gallery, London/Wikimedia Commons)Mansfield, certainly, was always one to see more than was strictly convenient for those around her, and her challenges to conventional feminine behaviour began early. Even so, by her teens she had learned how to be charming when she needed to be, and to attract a changing constellation of friends and admirers. From this point in Kimber’s book, Mansfield is increasingly dramatic, tragic, lively, and incorrigible as she falls in and out of love with her school friend Maata, a Maori princess, slips away during a dance to engage in scandalous behaviour with a nameless young man, or pens a Wildean vignette suffused with the decadent scent of a dying rose. It is impossible not to laugh when she adjures herself earnestly in her diary to ‘tell the truth more’, or to be moved when she speaks of her sense that she is ‘unlike others’, and that ‘there is no one to help me’.

Katherine Mansfield, 1917 (National Portrait Gallery, London/Wikimedia Commons)Mansfield, certainly, was always one to see more than was strictly convenient for those around her, and her challenges to conventional feminine behaviour began early. Even so, by her teens she had learned how to be charming when she needed to be, and to attract a changing constellation of friends and admirers. From this point in Kimber’s book, Mansfield is increasingly dramatic, tragic, lively, and incorrigible as she falls in and out of love with her school friend Maata, a Maori princess, slips away during a dance to engage in scandalous behaviour with a nameless young man, or pens a Wildean vignette suffused with the decadent scent of a dying rose. It is impossible not to laugh when she adjures herself earnestly in her diary to ‘tell the truth more’, or to be moved when she speaks of her sense that she is ‘unlike others’, and that ‘there is no one to help me’.

Kimber, however, seems to lose patience with her subject as her story progresses, describing her, for instance, as ‘egotistical’ and ‘wholly self-centred’, and at one point berating her for failing to understand that with freedom comes responsibility. Such throwaway comments do not do justice to the complexity of Mansfield’s situation, or, indeed, of adolescence itself. Yet in bringing together numerous biographical excerpts from Mansfield’s lesser-known writings in a single, readable account, Kimber has performed a service not only for those who worship at the Mansfield shrine, but also for those who simply want to know more of the tempestuous girlhood of the woman who wrote such masterpieces as ‘At the Bay’ and ‘Prelude’.

Comments powered by CComment