- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Custom Article Title: Klaus Neumann reviews 'What Is a Refugee?' by William Maley, 'Violent Borders: Refugees and the right to move' by Reece Jones, and 'Borderlands: Towards an anthropology of the cosmopolitan condition' by Michel Agier

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Three years ago, Australia was supposedly being overrun by asylum seekers arriving by boat. The situation was considered grave and dominated public debate and the ...

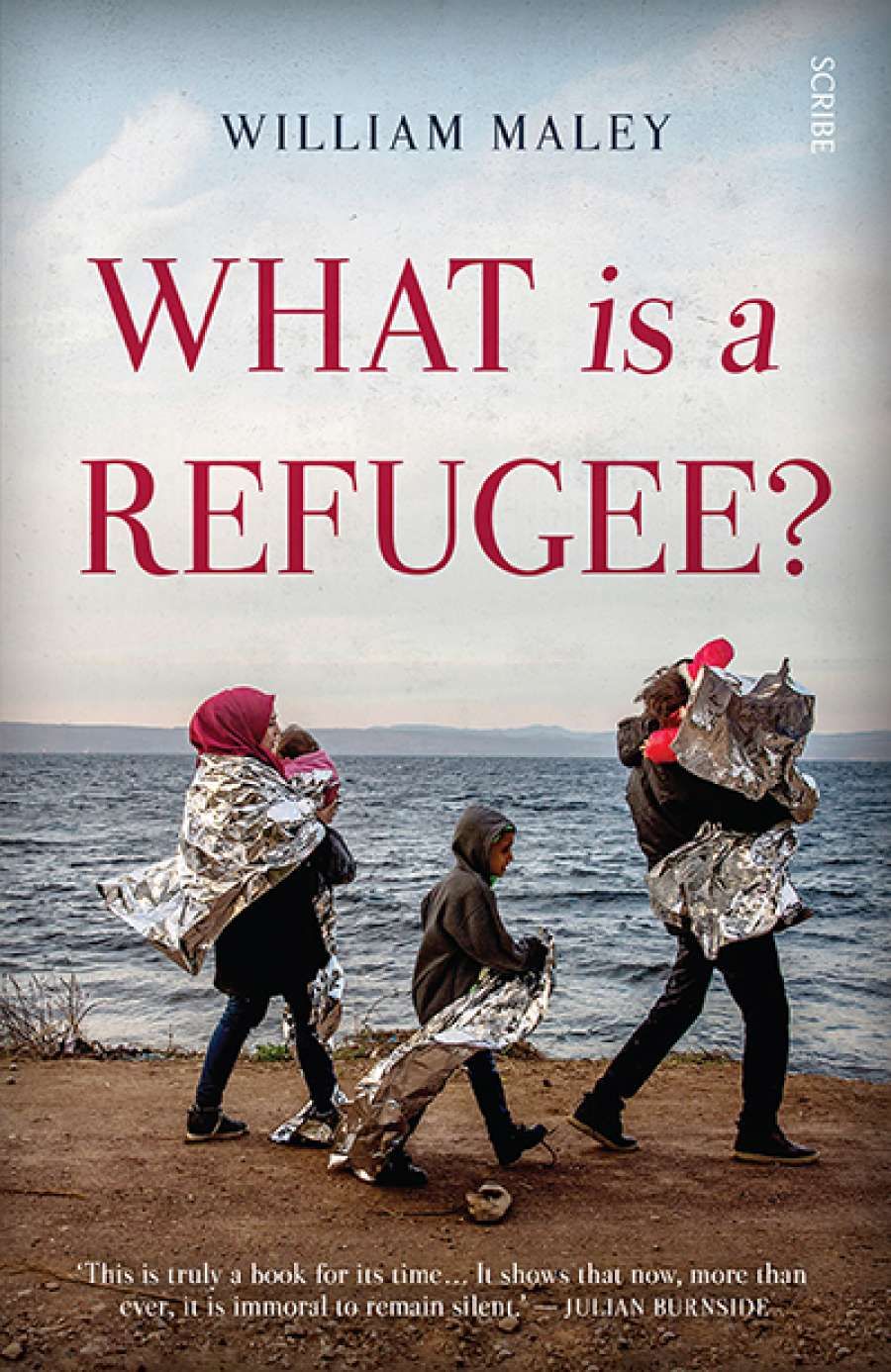

- Book 1 Title: What Is a Refugee?

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $29.99 pb, 285 pp, 9781925321869

While references to an unprecedented crisis abound in public debate, contributors to such debate also tend to assume that the context within which such movements occur, has remained the same: that nation-states, borders, and the controls that prevent the entry of unwanted aliens are somehow natural.

The last few years have seen the publication of a plethora of books analysing forced migration, and the response to refugees and asylum seekers in countries of the global North. William Maley’s What Is a Refugee? (Scribe, $29.99 pb, 285 pp, 9781925321869) is among the best informed and most wide-ranging of these books. He debunks many myths about refugees and asylum seekers. Not only does he show that ‘refugees are products of the system of states’; he also demonstrates that the pedigree of national sovereignty as we know it today reaches back only as far as the seventeenth century, and that it was only for the past one hundred years or so that states required migrants to produce passports and visas and thereby controlled access to their territories.

Answers to the question, ‘What is a refugee?’ are comparatively straightforward: a refugee is somebody who is commonly labelled as such, and/or meets certain criteria, such as those laid down in Article 1 of the 1951 Refugee Convention. Perhaps the more interesting and challenging question is: What are the people who are to be kept out, be it by Australia’s Operation Sovereign Borders, by a problematic deal between the leaders of the European Union and the autocratic ruler of Turkey, or by the wall that Donald Trump wants to build? As anybody familiar with refugee status determination procedures would know, it is difficult neatly to distinguish refugees from other migrants, even if the criteria of the 1951 Convention were the only yardstick.

However, Maley’s book is far more than an answer to the question, ‘What is a refugee?’ He explores the historical origins of today’s global refugee regime, discusses the root causes and enabling factors of mass displacement, and explains why refugees are the outcome of a political order based on territorially bounded nation-states. He illustrates his argument with examples from around the world, but keeps returning to the situation in Afghanistan, with which he is particularly familiar. His book also draws extensively on the Australian case. While it aims to provide a global picture, it is also an impassioned appeal for an end to the Australian government’s punitive policies and its ‘indifference to the basic principles of the rule of law’.

The inherently violent border regime that allows one part of the world to jealously guard its privileges is the subject of Reece Jones’s book, Violent Borders: Refugees and the right to move (Verso, $34.99 hb, 221 pp, 9781784784713), which I found to be the most readable of the three reviewed here. Violence accompanies nation-states’ attempts to defend their borders against presumed intruders. For example, between 2000 and 2015, India’s Border Security Force killed more than one thousand civilians along the border between India and Bangladesh.

The regime is violent also because efforts to make borders impenetrable force people to embark on life-threatening journeys. According to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), in the first eleven months of 2016 at least 4,699 migrants died while trying to cross the Mediterranean alone. There were presumably many more deaths that have not been accounted for. Australia’s offshore gulags in Nauru and on Manus Island are also part of this violent border regime. (Australian readers may be irritated by the fact that Jones has a rather sketchy knowledge of Australia’s policies and practices.)

The regime is violent also because efforts to make borders impenetrable force people to embark on life-threatening journeys. According to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), in the first eleven months of 2016 at least 4,699 migrants died while trying to cross the Mediterranean alone. There were presumably many more deaths that have not been accounted for. Australia’s offshore gulags in Nauru and on Manus Island are also part of this violent border regime. (Australian readers may be irritated by the fact that Jones has a rather sketchy knowledge of Australia’s policies and practices.)

According to Jones, border-related violence that targets migrants is only the latest instalment ‘in a long-term conflict between states and rulers ... and people who move in order to gain new opportunities or leave repressive conditions’. While the historical evidence provided by Jones is impressive, his argument omits the fact that the policies of ‘states and rulers’ enjoy widespread popular support in the countries of the global North, particularly in recent years. If the United States were indeed to build a wall at its southern border, it would be able to do so because American voters gave their new president a mandate for it.

I found Borderlands: Towards an anthropology of the cosmopolitan condition (Polity, $35.95 pb, 195 pp, 9780745696805, translated by David Fernbach), French anthropologist Michel Agier’s book about borders, in-between spaces, identity, and what he calls cosmopolitism, less inspiring. While it is on the one hand an incredibly rich essay which prompts reflection on important broader issues, it is also a frustrating read: disjointed, fragmentary, and enigmatic. This may be the result of a translation that often seems too literal, and resorts to neologisms and the frequent use of scare quotes.

Agier’s text is also less useful for somebody interested in forced migration because it is essentially about the dilemmas of anthropology. Since the 1980s, anthropologists, more so than other scholars in the humanities and social sciences, have repeatedly diagnosed a crisis of their discipline. Their writing has often been informed by an angst, as if they feared to become compromised, or implicated in what they set out to criticise.

Agier’s text is also less useful for somebody interested in forced migration because it is essentially about the dilemmas of anthropology. Since the 1980s, anthropologists, more so than other scholars in the humanities and social sciences, have repeatedly diagnosed a crisis of their discipline. Their writing has often been informed by an angst, as if they feared to become compromised, or implicated in what they set out to criticise.

Violent Borders and What Is a Refugee? betray the disciplinary backgrounds of their authors. Jones is interested in demarcations that curtail human movement, as a political geographer. Maley, a professor of diplomacy at the Australian National University, devotes separate chapters to ‘diplomacy and refugees’ and to humanitarian intervention, which don’t seem essential for his overall argument.

In conclusion, Maley writes: ‘The principal message of the book ... is that refugees are human, just like us. The problem is that all too often, we fail to treat them as human.’ This claim raises three issues. First, if refugees are ‘just like us’, there is no need to exclude ‘them’ from ‘our’ conversation. Second, refugees and non-refugees may have more in common than their humanity. A former head of Australia’s immigration department once wrote: ‘It is sobering to consider how easily today’s well-established and confident citizen can, by the overnight imposition of an unacceptable political and economic regimen, become tomorrow’s refugee.’ Finally, notwithstanding the fact that refugees do not comprise some kind of exotic species who warrant ‘our’ gaze, it is useful to pay close attention to different groups of actors, including irregular migrants, but also, for example, members of the security forces who are tasked with preventing refugees from reaching the global North.

This is where anthropologists often come in. Agier’s book opens with an ethnographic vignette. He describes a group of young Afghans encamped at a Greek port who try to cling to trucks that could take them on to a ferry to Italy. Their attempts to move on are regularly foiled by the police. The cat-and-mouse game involving migrants, the police, and truck drivers is observed from a safe distance by middle-class Greeks (who witness the scene through the plate-glass window of a fitness studio) – and by a surprisingly disengaged anthropologist.

Anthropologists could supplement the analyses of scholars such as Maley and Jones. While the latter can tell us what a refugee is and what borders are, anthropologists could tell us not only who the young Afghans are, but also provide detailed ethnographic portraits of the locals in the fitness studio, the police, and the truck drivers: their aspirations and fears, and their relationship with the outside world. Anthropological accounts could highlight the fact that refugees are also political subjects, who are not only the beneficiaries of compassion but who often claim rights.

Whatever their disciplinary background, those writing about borders and migration ought to tackle long-held assumptions: about the supposed crises precipitated by refugee movements and the alleged timelessness of nation-states and borders. Maley and Jones do that particularly well.

Comments powered by CComment