- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

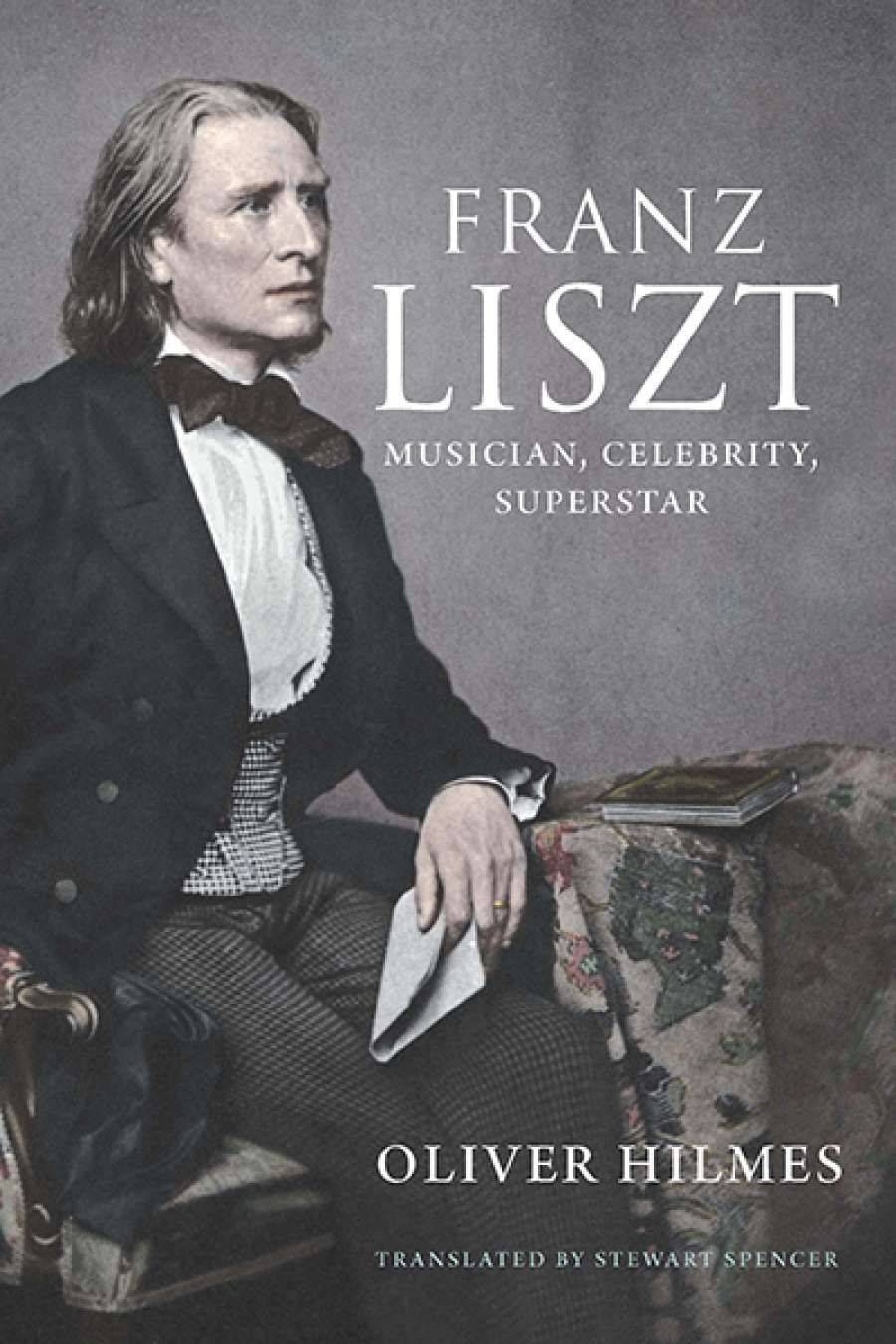

- Custom Article Title: David Larkin reviews 'Franz Liszt: Musician, celebrity, superstar' by Oliver Hilmes, translated by Stewart Spencer

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Franz Liszt

- Book 1 Subtitle: Musician, celebrity, superstar

- Book 1 Biblio: Oliver Hilmes, translated by Stewart Spencer

Still more ink is expended on the two women who were his long-term companions: Comtesse Marie d’Agoult, who eloped with Liszt, bore him three children and after the break-up wrote an excoriating roman-à-clef about him; and Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, who left a failed marriage in native Poland with her young daughter to live with Liszt in provincial Weimar. Hilmes makes us aware of the social opprobrium that both women faced as a result of their choices, and in general draws attention to the less beatific aspects of both connections. For instance, as Liszt and a recently pregnant Marie arrived in Switzerland in 1835, the former wrote: ‘We are both in fairly good spirits and are not thinking of becoming unhappy.’ The sorry story of Carolyne’s attempts to obtain an annulment, and the vested interests which thwarted her ambition to marry Liszt at the eleventh hour are also recounted in detail.

On the whole, Hilmes is even-handed in his treatment of the glitzy and the grimy aspects of his subject, and steers clear of the hagiographic tone infusing Alan Walker’s definitive three-volume study of the composer (1983–96). He disapprovingly describes the elderly Liszt as setting a bad example for his young pupils by his excessive drinking (two of his greatest pupils, Alfred Riesenauer and Arthur Friedheim, succumbed to alcoholism) and forcing them to smoke. Still less palatable to modern sensibilities is Liszt’s harsh treatment of his three children, who lived with their grandmother in Paris, and were forbidden from seeing their mother. His daughter Cosima’s emotional remoteness from her father late in his life can perhaps be thought of as a form of karmic justice. However, Liszt’s disinterested help for other artists is also featured, not least his artistic and financial support of Wagner.

Liszt’s legendary status within his own lifetime rested firmly on his pianistic accomplishments, yet these only occupied the first half of his career. At the age of thirty-five, he abruptly quit as a touring virtuoso and settled in Weimar to devote himself to composition and to supporting other aspiring artists, whether through his piano teaching or through conducting new music. Hilmes consequently only devotes the first third of his book to Liszt’s years as a performer. There is little new in this retelling, although he does provide some welcome specifics as to Liszt’s earnings (and occasional losses) during this period. Hilmes doesn’t credit the cynical Heinrich Heine’s suspicions that the ecstatic audiences were seeded with paid applauders, but he does acknowledge ‘Liszt’s gift for self-promotion’.

Franz Liszt with his pupils - 1st row: Saul Liebling, Alexander Siloti, Arthur Friedheim, Emil von Sauer, Alfred Reisenauer, and Alexander Gottschalg. 2nd row: Moriz Rosenthal, Viktoria Drewing, Alexandrine Paramanoff, Franz Liszt, Annette Hempel-Friedheim (A. Friedheim's mother), and Hugo Mansfeldt. (photograph by Louis Held [1851–1927], Wikimedia Commons)

Franz Liszt with his pupils - 1st row: Saul Liebling, Alexander Siloti, Arthur Friedheim, Emil von Sauer, Alfred Reisenauer, and Alexander Gottschalg. 2nd row: Moriz Rosenthal, Viktoria Drewing, Alexandrine Paramanoff, Franz Liszt, Annette Hempel-Friedheim (A. Friedheim's mother), and Hugo Mansfeldt. (photograph by Louis Held [1851–1927], Wikimedia Commons)

While this book provides a highly readable account of Liszt the untouchable pianist and Liszt the attractive but flawed human, it skimps in its treatment of Liszt the composer. A single page is given to the major creative accomplishments of his thirteen years in Weimar: his development of a poetically infused orchestral music, which led to the invention of the single-movement symphonic poem, and the epic multi-movement Faust and Dante symphonies. Perhaps more was not to be expected: the dust-jacket describes Hilmes as holding a PhD in twentieth-century history, and he is best known in the English-speaking world for his biography of Cosima Wagner (2010), a musically significant figure but not a creative one.

Nonetheless, the primary reason why we care about Liszt today is because of the compositions he left behind, particularly those for piano. We can learn of Liszt’s significance for his era through accounts of Lisztomania, but his significance for ours is because we can be thrilled anew by performances of his virtuoso Mephisto Waltz, or transported by his glorious Sonata in B minor. Hilmes may have shied away from in-depth discussion of his works because of the inherent difficulty of capturing the experience of music in words, but these works are what has enabled Liszt to fulfil his ambition ‘to hurl [his] lance into the boundless realms of the future’.

Comments powered by CComment