- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Custom Article Title: Rachel Robertson reviews 'A Tear in the Soul' by Amanda Webster

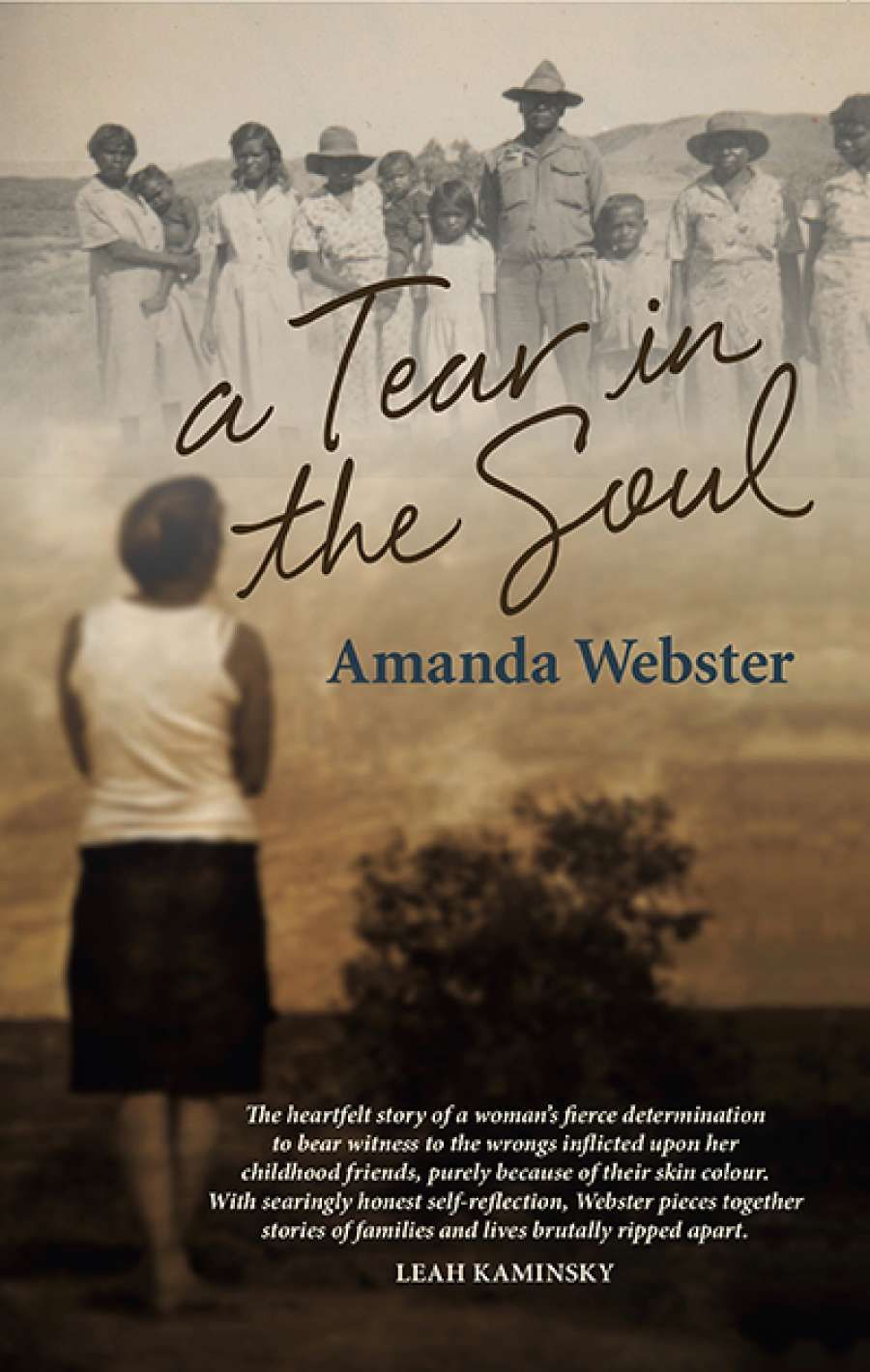

- Book 1 Title: A Tear in the Soul

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth $29.99 pb, 288 pp, 9781742235134

Gregory is initially wary about talking to Webster; the book delicately unfolds the complexities of their relationship and the developing trust between them which eventually leads to a warm friendship. He becomes Webster’s guide into the lives of the Kurrawang children, and takes her to meet his family and Bronwyn. In the course of her interviews with children and staff who lived at Kurrawang and her research into the archives, Webster pieces together the first, albeit partial, history of the Kurrawang Mission. Many of her childhood assumptions are challenged; the children were not orphans but part of the Stolen Generations. The conditions at Kurrawang were harsh and overcrowded, families were separated, and the children were treated cruelly at times, while also experiencing some care and support.

Bronwyn is homeless and living in the bush when Webster visits her. The scenes where the two friends unite are written with a light touch; they are pleased to see each other, but the differences between them are obvious and make their interactions complex and sometimes fraught. Webster is particularly caught up in questioning whether she should give money to Bronwyn or direct it to a community group that supports Aboriginal people. Resources are partly what she considers to be her reparation for the past: for her own relative affluence and ease compared with her Aboriginal peers’ struggles and poverty; for her grandfather’s role as local Aboriginal Protector; for white Australia’s treatment of Aboriginal peoples. More than money, though, this book is a form of reparation, an attempt to represent the reality of children’s lives in Kurrawang, the pain and damage they have experienced since, and to honour their resilience. Webster says, ‘I don’t believe it is possible to hurt another person without hurting oneself, an invisible hurt, a tear in the soul that allows the essence of one’s humanity to leak out, like bleeding from a cut ... A collective group can’t hurt another collective group without hurting itself.’ She believes that saying sorry ‘without some form of reparation’ is close to meaningless. This is not the act of someone trying to absolve herself from guilt or heal her ‘tear’, but rather a deeply moral exploration of our joint responsibilities for others’ sufferings, whether caused by our ‘collective group’ or not.

The most moving parts of the book are individuals’ stories, like Gregory’s tale of survival and his son’s response to his father’s experiences, and like the stories of Beverly Joy and Catherine, who lived at different times at Kurrawang, who both experienced rape there, and who, as Webster only discovers much later, were teenage mother and daughter. There is a heart-rending moment in the book when Webster finds out Beverly Joy’s real name (rather than the one given to her by the missionaries) and is able to tell it to her daughter Catherine for the first time. ‘Again I thought how odd and wrong it was that it fell to me to deliver information about a mother to an Aboriginal person.’

Amanda Webster (photography by Justine Gordon)

Amanda Webster (photography by Justine Gordon)

An interesting aspect of this book is the way the narrator changes as she learns more about Kurrawang and the goldfields Aboriginal community. She starts to learn to read the land and its people. She says of Kurrawang, ‘It was one of the few places I’d been where the veil between past and present seemed as fine as dust. Or as thin as a layer of skin. I was beginning to understand that landscape is never neutral. It has memory.’ She recounts her blunders in trying to understand the Indigenous people and to behave in culturally appropriate ways. She has thought deeply about the ethical implications of her work, and her Epilogue addresses the issue of when it is acceptable for a white person to tell such a story. Webster’s sensitivity and thoughtfulness, her careful processes, her willingness to own the dark aspects of her own family’s past, and her collaboration with Gregory Ugle all contribute to making this a strong and ethical book that adds to our understanding of West Australian history.

Comments powered by CComment