- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Custom Article Title: Gabriel García Ochoa reviews 'The Man Who Invented Fiction: How Cervantes ushered in the modern world' by William Egginton

- Custom Highlight Text:

The four-hundredth anniversary of Miguel de Cervantes’s death serves as a good reminder of the influence and importance of his oeuvre, and perhaps too of our strange obsession with ...

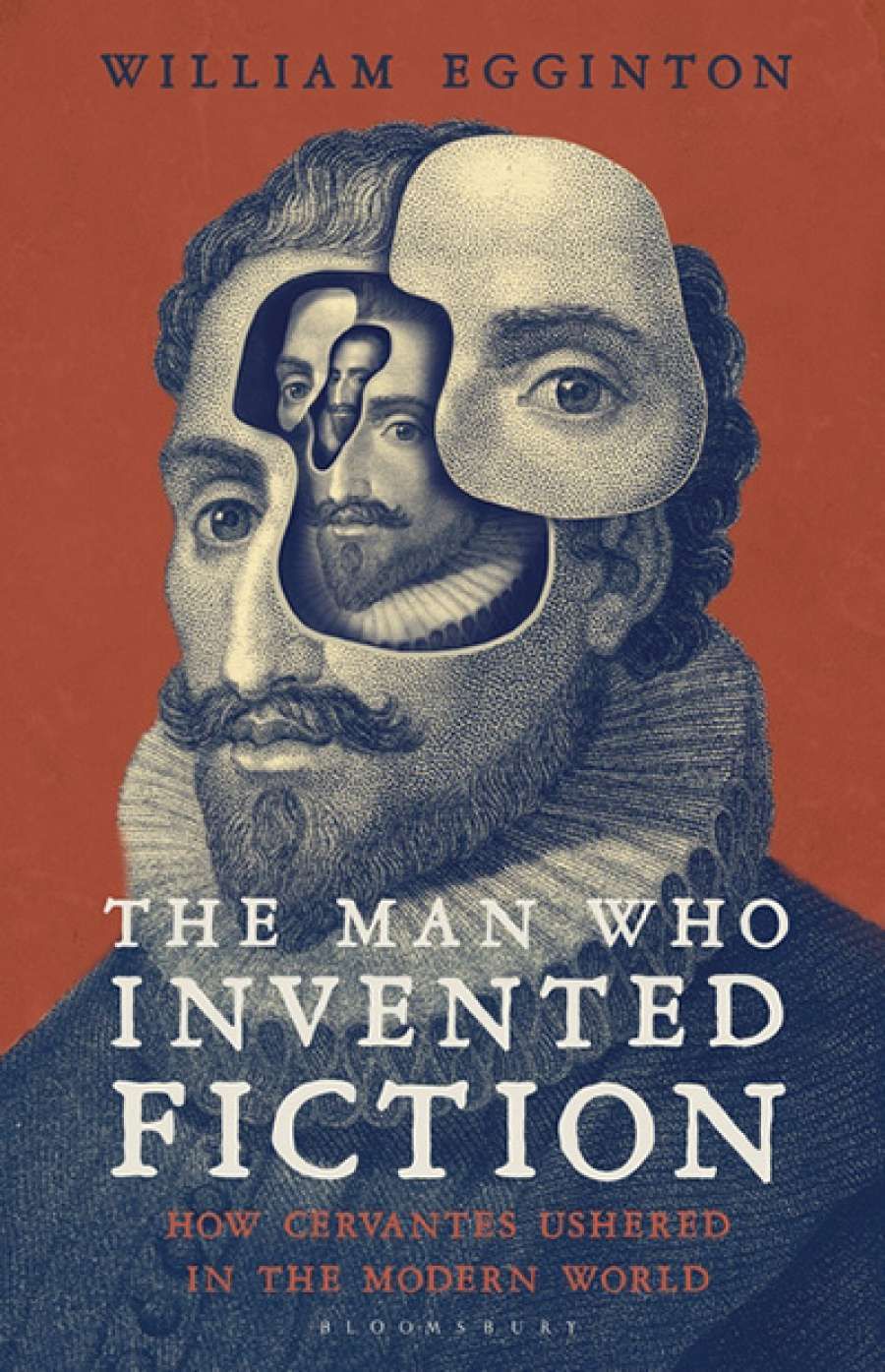

- Book 1 Title: The Man Who Invented Fiction

- Book 1 Subtitle: How Cervantes ushered in the modern world

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury $49.99 hb, 262 pp, 9781408843840

Stepping into the realm of Cervantes’s works, in particular Don Quixote, has a dizzying effect for any reader. It is a funhouse for the mind. The heroes in Cervantes’s texts are neither paladins nor magicians; they are readers who like to think of themselves as paladins and magicians, much like us. By placing the reader in the text, Cervantes created a new space that showed us not only how different people interpret different situations, but also how we misinterpret them. What to Sancho Panza seems to be a cluster of windmills is a throng of giants to Don Quixote, and it may be something different to someone else. In this sense, the fiction of Cervantes is not a mirror of the world, it is a picture of our subjectivities, both individual and collective. It is not so much an extension of our reality as an extension of our human condition: half factual, half imagined, partially deluded, and open to interpretation. In this new space of rumination, all manner of ideas are open to examination, morality is explored without moralising, and both truth and reality become subjective, which is, indeed, a modern way of looking at the world.

Egginton argues that Cervantes was partly able to create this new subjective space because he wrote across genres. Few people know that Cervantes wrote for the theatre. Many of the scenarios in his novels and short stories were often recycled from stage to page. According to Egginton, this allowed him to bring into his fiction a narrative style previously associated only with drama, which consisted in examining a particular situation from the points of view of different characters. Such was the case, for example with the plot of Cervantes’s play The Business of Algiers, later used in the short story ‘The Captive’s Tale’, which was eventually inserted into the first part of Don Quixote.

The plurality of perspectives in Cervantes’s works was exacerbated by his need to process trauma through writing. Egginton argues that part of the success of Don Quixote, and many of Cervantes’s other works, lies in the fact that Cervantes’s adventurous life – which included the loss of the use of his left hand during the Battle of Lepanto, capture by corsairs at the command of the feared Greek pirate Dalí Mamí, and being sold as a slave to Hasan Pasha, Impaler of Christians – was, to an extent, turned into fiction. Egginton suggests that Cervantes may have processed the trauma of these experiences by writing and rewriting about them in fictionalised form, often analysing the same scenario from the points of view of different characters, exploring how things could have been for him. This reinforced the perspectivism in his prose that was brought across from the theatre; moreover, it helped develop what Egginton calls ‘literary empathy’, which is what happens when we use literature to understand the world from someone else’s point of view, a skill referred to nowadays in academic circles as ‘cultural literacy’.

The monument to Cervantes at the Plaza de España in Madrid (Wikimedia Commons)The Man Who Invented Fiction skirts the edges of novelised biography and critical essay. Egginton’s prose is engaging, his ideas captivating, and he is careful to keep his clear love for Cervantes in check. After all, hidalgolatry, just like bardolatry for Shakespeare, can quickly turn into a serious condition affecting literary scholars most particularly, but Egginton draws a clear line between his theorisations and the facts of Cervantes’ life in relation to his oeuvre. The proposition in his title, however, while furiously argued throughout the book, ends up becoming a self-fulfilled prophecy: if you define ‘fiction’ as what Cervantes wrote, and then claim that Cervantes invented fiction, there is little room to err.

The monument to Cervantes at the Plaza de España in Madrid (Wikimedia Commons)The Man Who Invented Fiction skirts the edges of novelised biography and critical essay. Egginton’s prose is engaging, his ideas captivating, and he is careful to keep his clear love for Cervantes in check. After all, hidalgolatry, just like bardolatry for Shakespeare, can quickly turn into a serious condition affecting literary scholars most particularly, but Egginton draws a clear line between his theorisations and the facts of Cervantes’ life in relation to his oeuvre. The proposition in his title, however, while furiously argued throughout the book, ends up becoming a self-fulfilled prophecy: if you define ‘fiction’ as what Cervantes wrote, and then claim that Cervantes invented fiction, there is little room to err.

Throughout the first and second parts of Don Quixote, the poor Don’s delusions are scoffed at by every character in the novel, who, like us, know that the dear hidalgo is infatuated with stories that are not real. But we tend to forget that neither are those scoffing characters, who are also the product of Cervantes’s imagination. In that case, are we readers so different from Don Quixote, if we continue to be in love with a knight of mournful countenance who was born over four hundred years ago, but never existed?

Comments powered by CComment