- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Custom Article Title: Paul Strangio reviews 'John Curtin: How he won over the media' by Caryn Coatney

- Custom Highlight Text:

John Curtin occupies the top tier in the pantheon of Australian national leaders. ‘Expert’ rankings of former officer holders – a practice lately imported from the United States, where ...

- Book 1 Title: John Curtin

- Book 1 Subtitle: How he won over the media

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian Scholarly Publishing, $39.95 pb, 228 pp, 9871925333411

Recent studies have supplemented the wartime saviour-martyr narrative of Curtin. One portrays him as architect of the postwar economy; another argues that his finely calibrated (and traditional) vision of Australia’s geo-political destiny as an active partner within the British empire has been unduly overshadowed by the focus on his famed ‘looks to America’ message of December 1941. Now, Caryn Coatney has written a commendable book further illuminating Curtin’s wartime leadership by exploring his media management practices. It has long been recognised that the former journalist Curtin deftly nurtured a relationship with the Canberra press gallery to win their cooperation in prosecuting the war effort. Coatney, however, draws upon archival research and the oral histories and autobiographies of journalists to delve more intricately into Curtin’s novel mass communication techniques.

The book sketches the media milieu of wartime Australia. It was an era in which the public were avid press consumers, typically buying the morning daily from street corner newspaper boys. The pre-eminence of the press as a news source was, however, under challenge. In 1939, the ABC’s first federal political correspondent joined the Canberra press gallery and Australians were regularly tuning into radio news broadcasts. Picture theatres were another increasingly important news outlet, with audiences ‘watching creaking news announcements about the war’.

Coatney confirms that central to Curtin’s media management were daily informal briefings of members of the press gallery in which he shared off-the-record information. She contrasts Curtin’s ‘egalitarian’ treatment of journalists with Robert Menzies’ aloofness towards them, which had had the effect of alienating news reporters and contributed to his first unhappy stint as prime minister (1939–41). Though Curtin’s cultivation of the press gallery was rewarded with them (mostly) maintaining confidences and sympathy with him, this did not translate into an easy relationship with press barons Keith Murdoch and Frank Packer. Their anti-Labor prejudices were unleashed once the darkest days of the war passed. Murdoch waged a vitriolic but unsuccessful campaign against Curtin at the 1943 federal election. The proprietors also chafed at the Labor government’s censorship regime, colluding in an open revolt against the regulations while Curtin was overseas in 1944.

John Curtin and US General Douglas MacArthur meet at Parliament House, 1942 (Wikimedia Commons)

John Curtin and US General Douglas MacArthur meet at Parliament House, 1942 (Wikimedia Commons)

Curtin and his sometimes ‘intimidating’ press secretary, Don Rodgers, were alive to the changing media landscape. Stanley Bruce made the first primitive forays into campaigning over the airwaves in the 1920s, while Joseph Lyons’s broadcasts projected a reassuring persona during the economic uncertainties of the following decade. Yet Coatney suggests Curtin was the first prime minister to truly command that technology. By 1942, his radio addresses were being described as ‘armchair’ or ‘fireside’ chats in a clear analogy to Franklin Roosevelt’s broadcasts in the United States. The same year, he became the first Australian leader to have a speech directly transmitted into the United States. Curtin’s international media activities are indeed another thread of Coatney’s account, although evidence of his effectiveness in that sphere is difficult to sustain.

While there was undoubtedly a cross-fertilisation of communication techniques among the Allied leaders, Coatney argues the image-making of Curtin was distinctive. In newsreels he was presented as a plain ‘man of the people’ as opposed to the ‘aristocratic’ bearing of Roosevelt and the ‘flamboyant’ Churchill. His radio addresses were pitched at a ninth-grade reading level and spoken slowly. Yet Curtin did not condescend to his domestic audience. Preparing his December 1941 address to the nation following Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor, in which he made ‘Australia’s first independent declaration of war’, Curtin made a last-minute amendment to his script by borrowing a verse from the English radical poet Algernon Charles Swinburne: ‘Come forth, be born and live, Thou that hast help to give ... Hasten thine hour and halt not, till thy work be done.’

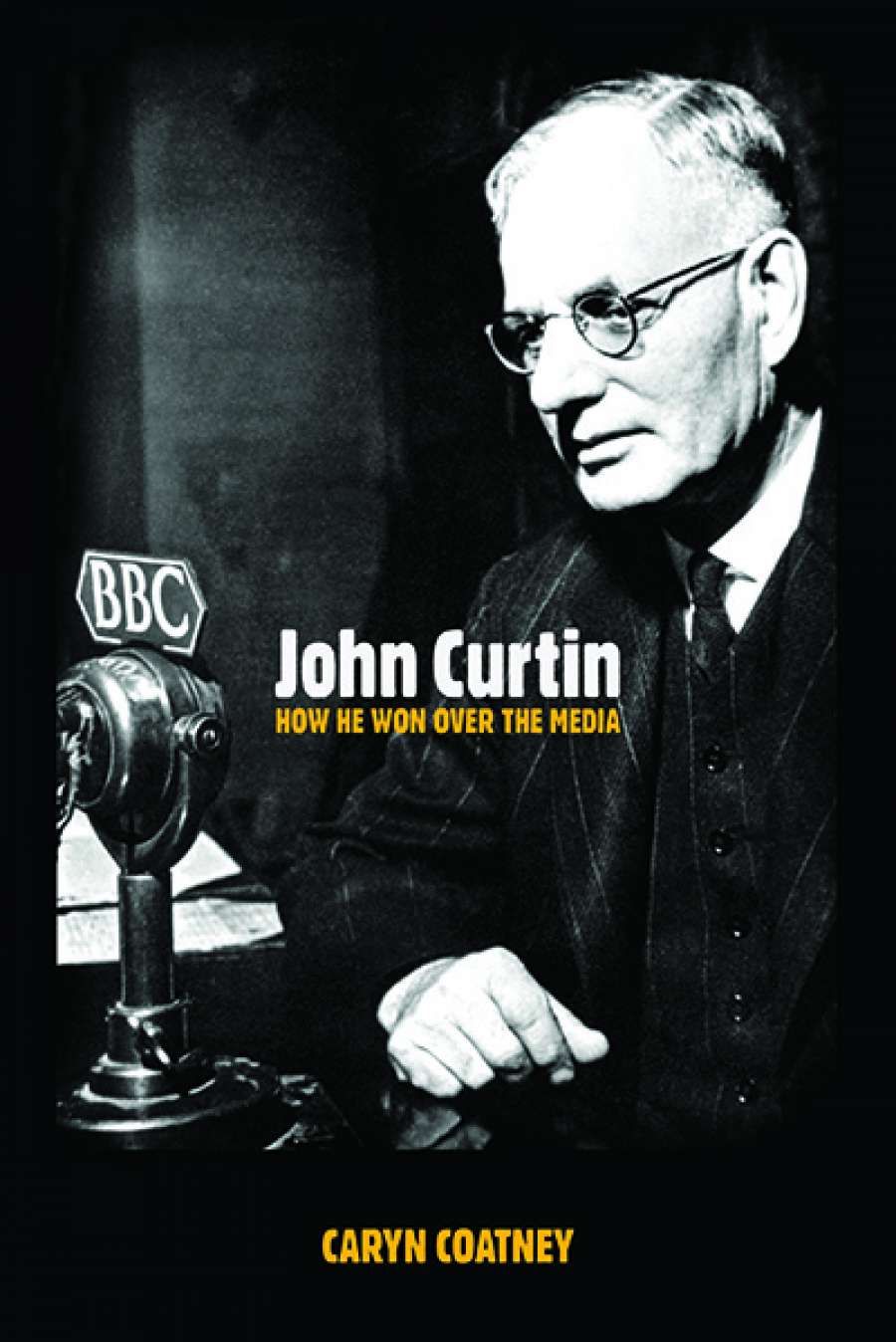

Prime Minister John Curtin, 1942 (State Library of Queensland)

Prime Minister John Curtin, 1942 (State Library of Queensland)

Though informative and worthy, the book is not without fault. On occasions the prose is awkward and the narrative uneven. These are possibly the product of injudicious editing down from a larger thesis. Coatney’s slightly implausible assertion that ‘Curtin’s mass communication strategies provide lessons for contemporary democratic leaders’ is also unfulfilled. The discretion showed by journalists in downplaying Curtin’s failing health in 1944–45 – mirroring the circumspection of the American press on Roosevelt’s condition – emphasises how relatively quaint was their media age compared to today’s communication blitzkriegs. Curtin’s achievement in mastering that era is nonetheless undiminished.

Comments powered by CComment