- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

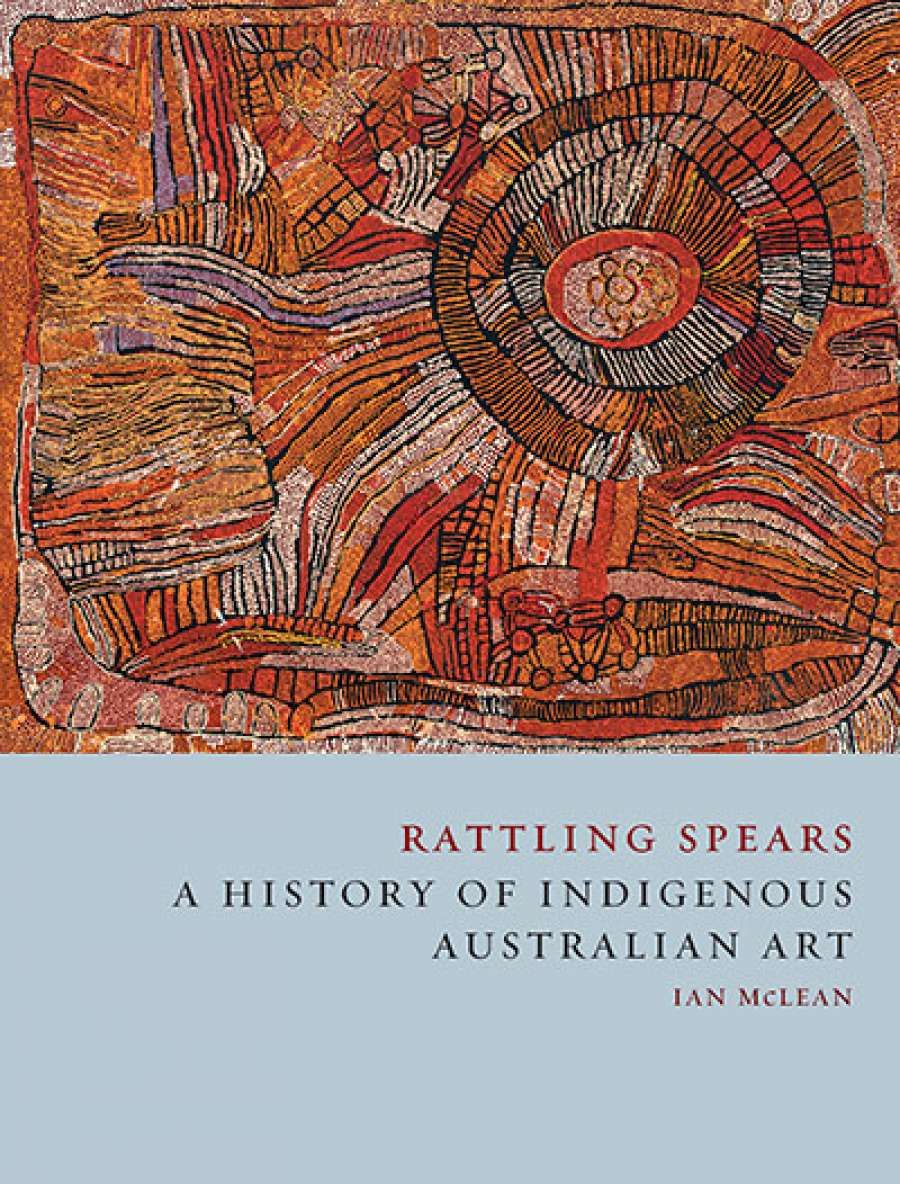

- Custom Article Title: Billy Griffiths reviews 'Rattling Spears: A history of indigenous Australian' art by Ian McLean

- Custom Highlight Text:

This beautifully illustrated book explores the ways in which Indigenous Australians have responded to invasion through art. ‘Where colonists saw a gulf,’ writes art historian Ian ...

- Book 1 Title: Rattling Spears

- Book 1 Subtitle: A history of indigenous Australian art

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $59.99 hb, 296 pp, 9781780235905

McLean describes the book as ‘the first full art-historical narrative of Indigenous Australian art’. As opposed to other historical or anthropological overviews of the field, McLean focuses on integrating Aboriginal ‘responses to modernity’ into the language and theory of the contemporary art world. The ritual spearing of Governor Arthur Phillip in 1790 is thus reconsidered as ‘performance art’, while Bungaree’s performances in early Sydney are interpreted as ‘mock baroque satires’ redolent of ‘the sort of kitsch buffoonery that the Zurich Dadaists would make into avant-garde art ninety years later’. In Victoria, painter William Barak is celebrated as ‘a strategic essentialist’, while Tommy McRae’s silhouette sketches are analysed as ‘cosmopolitan’ expressions of ‘dandyism’. Although the text is laden with such specialist language, it is a necessary component of McLean’s argument: these are significant artists whose work should be understood in the context of world art movements.

The book is broken into three parts: ‘Empire’, ‘Nation’, and ‘Post-Western’. The opening chapters, which move from 60,000 years ago to 1900, are curiously placeless, considering that Aboriginal art is intimately linked to country. McLean sets the tone in the introduction, citing an Indigenous busker playing didgeridoo (a northern Australian artefact) in Circular Quay as a reminder of ‘the special history of this place’. ‘This place’ is the whole of Australia, ‘modernity’ is represented by the British Empire, and the many hundreds of Aboriginal nations are forged into one ‘age-old’, pan-continental culture. In this way, the Sydney Opera House becomes, in a blurring of regional cultures, ‘a shining white Rainbow Serpent arcing up from the site of invasion’.

In being ‘art-historical’, not historical, McLean allows himself the freedom to make broad statements such as: ‘Nothing much changed in the next fifty years.’ But it is disappointing how little he engages with the existing scholarship in the fields of history, archaeology, and anthropology. As a result, he casually repeats contested dates for rock art and falls back on the largely rejected terminology of ‘shamanism’ and ‘the Neolithic’ to describe Aboriginal society pre-contact.

Yet the book never ceases to be engaging, and it gathers momentum over the course of the narrative. McLean beautifully evokes rock art as a performative act – ‘the residue of ritual’ – and later touches on the ways in which ancient motifs are echoed in contemporary art: how Alec Mingelmanganu, for example, brought Wanjinas to life on canvas. In ‘Nation’, McLean explores the tension between tradition and modernity in the bark painting centres in Arnhem Land, comparing the ‘anyhow’ missionary paintings made for tobacco with the more serious artworks created for visiting anthropologists. Such commissioning practices, alongside the ‘invisible hand of the artworld’, inevitably shaped the course of Indigenous art. But McLean is always quick to underline the agency of individual artists and movements: ‘Do not doubt that the Indigenous turn to abstraction is not aimed at the Western artworld with all the power and accuracy of a well-thrown spear.’

Wanjina, c.4000 bpe, earth pigments on rock shelter. The Wanjinas are over five metres long. Isdell River, central Kimberley. (Photograph by Mike Donaldson. First published in Kimberley Rock Art – Volume Three: Rivers and Ranges by Mike Donaldson, [Wildrocks Publications, 2013])

Wanjina, c.4000 bpe, earth pigments on rock shelter. The Wanjinas are over five metres long. Isdell River, central Kimberley. (Photograph by Mike Donaldson. First published in Kimberley Rock Art – Volume Three: Rivers and Ranges by Mike Donaldson, [Wildrocks Publications, 2013])

Albert Namatjira was the forerunner of the contemporary Indigenous art scene, and Rex Battarbee’s management of Hermannsburg became the model of the modern art centre. Through Namatjira’s watercolours, Indigenous art began to be recognised as ‘modern’, even though ‘his Western supporters believed that his art exemplified the promise of acculturation rather than transculturation’. But it was the Papunya Tula art movement that decisively transformed Aboriginal art from anthropological curio to celebrated fine art commodity. McLean gives us a rich assessment of the forces (both ancestral and bureaucratic) that played a hand in its founding. He argues that ‘while the Papunya art movement began 200 years after Cook landed at Botany Bay, in many respects it is an example of contact art’.

With the boom of the canvas economy in the 1980s, remote art centres became increasingly defined by the art world’s innate fascination with individual masters and masterpieces. ‘Genius, not ethnography, was the new catchword.’ These are the strongest chapters of the book, featuring rich vignettes on remote masters such as John Mawurndjul and Emily Kame Kngwarreye. McLean also explores questions of identity through New Wave artists such as Trevor Nickolls, who resisted the label ‘Indigenous’ and described his art as being caught between ‘machinetime and dreamtime’.

Machine Time & Dreamtime by Trevor Nickolls, 1984, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, (Flinders University Art Museum Collection, Adelaide/Viscopy)

Machine Time & Dreamtime by Trevor Nickolls, 1984, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, (Flinders University Art Museum Collection, Adelaide/Viscopy)

By the 1990s, urban Indigenous art defied categorisation. Despite the increasingly divergent themes, subjects, and approaches, McLean identifies a unifying element, arguing that a ‘deep anger at historical injustice is the driving force of nearly all urban art’. He highlights Gordon Bennett and Tracey Moffatt in particular as setting the agenda with their ‘post-Western cosmopolitanism’, making them ‘not just the most significant urban Indigenous artists but the most significant contemporary Australian artists of the 1990s’.

The books concludes with an esoteric essay on ‘A Theory of Indigenous Art in the Age of Modernity’, in which McLean unpacks Richard Bell’s intentionally ambiguous quote: ‘Aboriginal art – it’s a white thing.’ This, he believes, is only half the story. Aboriginal art has played a powerful role in shaping the Western art world, and vice versa. It is a two-way process. ‘When worlds collide,’ he reflects, ‘one or both are ripped apart or there is the intense heat of fusion.’ Rattling Spears, while faltering at points, burns with the brightness of that fusion.

Comments powered by CComment