- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

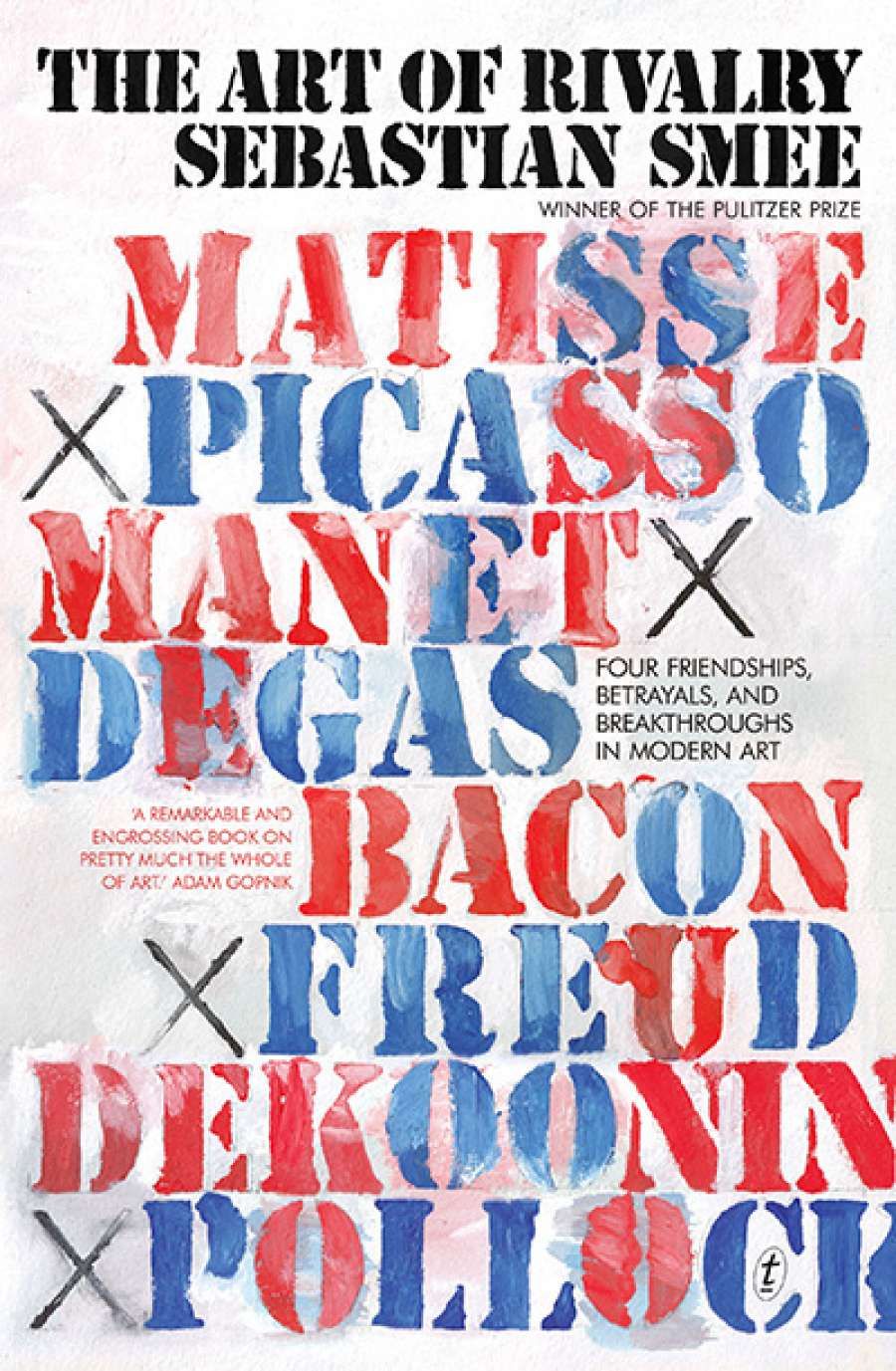

- Custom Article Title: Miriam Cosic reviews 'The Art of Rivalry: Four friendships, betrayals, and breakthroughs in modern art' by Sebastian Smee

- Custom Highlight Text:

It seems a particularly masculine take on the processes of art to examine the way rivalry spurs on creativity and conceptual development. Yet this is not the book the Boston Globe’s ...

- Book 1 Title: The Art of Rivalry

- Book 1 Subtitle: Four friendships, betrayals, and breakthroughs in modern art

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $34.99 pb, 416 pp, 9781925240351

Freud was a grandson of Sigmund Freud, and high-level intercession had enabled his family to escape Hitler’s Germany in 1938. From the age of ten, Freud attended privileged schools in England; he grew into a young man Smee describes as ‘mercurial, ardent and unpredictable, attracted by danger, and, to most people who encountered him, extremely attractive’. He was his mother’s favourite among her three sons, and Smee describes him as acting with the ‘flair and impunity, but also the tenderness and sensitivity, of someone whose mother adored him’. Smee’s admiration perhaps causes him to overlook the serial betrayals of Freud’s romantic life.

Bacon, the son of a retired army captain who ran the family with military precision, did not have such a blessed childhood. Annoyed by young Francis’s sickly demeanour, and perhaps sensing his son’s emerging homosexuality, Francis’s father arranged to have his grooms horsewhip him, in order to ‘make a man of him’. Bacon was thrown out of home at fifteen when his father found him dressed in his mother’s underwear.

Thirteen years separated them, and by the time the two artists met Bacon was beginning to establish a reputation for unsettling imagery of human bodies, often twisted and unfinished, often eerily suspended in space, the paint thickly laid on, which owed as much to photography and film, Smee points out, as to continental modernism. Freud, who was only twenty-two at the time, was awed both by Bacon’s work and by his work ethic, as well as his expansiveness, generosity, derision, and general wildness, and began visiting his studio regularly. Bacon’s partner, Eric Hall, was jealous of Freud and ‘came to loathe him’, though the consensus seems to be that the two artists were never physically intimate.

‘Influence is erotic’, Smee writes, adding that Bacon bankrolled Freud for a long time. ‘And yet, even as he admitted Bacon’s example, he now found himself caught up in a struggle to hold his own course.’ Smee is soon showing us, mostly through conjecture, how the influence worked both ways, including the younger man’s precisions on the older man’s work.

If Bacon’s work was urgent, passionate, often ugly but always persuasive, Freud’s was cold, almost callous in its distance from emotion. Smee refers to Freud’s ‘increasingly aggressive attack on sentimentality’. That Bacon, who was an alcoholic, suffered terribly, including violence, in his long-term relationships with other men, and that Freud dominated the women in his life seems evident in their canvases, though Smee doesn’t draw the comparison.

Bacon says that as he grew older he realised that he didn’t need extreme subject matter but could find sources for his painting in his own life. Smee sees evidence of shifting influence in this. ‘Certainly Bacon’s focus, from this time forward, on constantly reiterated portrayals of a small group of intimate acquaintances strongly suggests the influence of the young man.’ Yet by the early 1970s their relationship was as good as over, and Smee has some terrible quotes from both of them on money and professional jealousy. Freud called Bacon ‘bitchy’ and ‘bitter’.

One example will have to suffice, but Smee draws out the interpersonal aspects of all the rivalries in similar manner. The brawling Pollock versus the debonair de Kooning; the socially conventional Manet versus Degas, who was always too interested in under-age ballerinas (another point Smee all but overlooks); the hesitant Manet versus the gigantic appetites of Picasso: the red thread running through all these relationships is a magnetic swing between attraction and repulsion, precision and boldness, care and risk taking, in temperament and in art, within each pairing, even as all involved were pushing the boundaries of modernism.

Despite his previous scholarship on Freud, Smee delivers the most interesting art criticism in his very good chapter on Picasso and Matisse, even though one might think there was little left to say about either artist. The freshest chapter seems to be that on Manet and Degas: Smee’s forensic skill reveals sides of both men that this writer, at least, had not fathomed. The American expressionists are endlessly fascinating, if only for the surprise of their rise in the New World, but in Smee’s hands the Pollock–de Kooning chapter is riveting. [Disclosure: Sebastian Smee was appointed national arts critic under Miriam Cosic’s arts editorship at The Australian and remained in the position throughout her tenure.]

Willem de Kooning (Smithsonian Institute Archives, Wikimedia Commons)

Willem de Kooning (Smithsonian Institute Archives, Wikimedia Commons)

In a nod to the spirit of the times, Smee explains why he chose only male artists. The relationships of great women artists with other artists were too tainted by romantic entanglement to fit the brief. Women did not, apparently, have intense relationships with mentors, collaborators, supporters, prodders, or protégés they weren’t having sex with. Lee Krasner looms large in the Pollock chapter, not as an artist in her own right but as Pollock’s enabler, and her status as harridan to many in the American art world is repeatedly mentioned. The powerful New York dealers who handled Pollock and de Kooning and happened to be women – Betty Parsons, for example – get passing mention and no exploration of their skill as promoters or salespeople.

Well, this is the way the world is, as most women are keenly aware and most men are not. Set it aside, for Smee’s book is full of interest and elegance and compelling insights into formative moments in, not just art, but Western culture more broadly.

Comments powered by CComment