- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Custom Article Title: Sheila Fitzpatrick reviews 'Virtuosi Abroad: Soviet music and imperial competition during the early Cold War, 1945–1958' by Kiril Tomoff

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Soviet violinist David Oistrakh made a triumphant tour of Australia in 1959, a few years after his wildly successful New York début. Along with pianist Emil Gilels and cellist ...

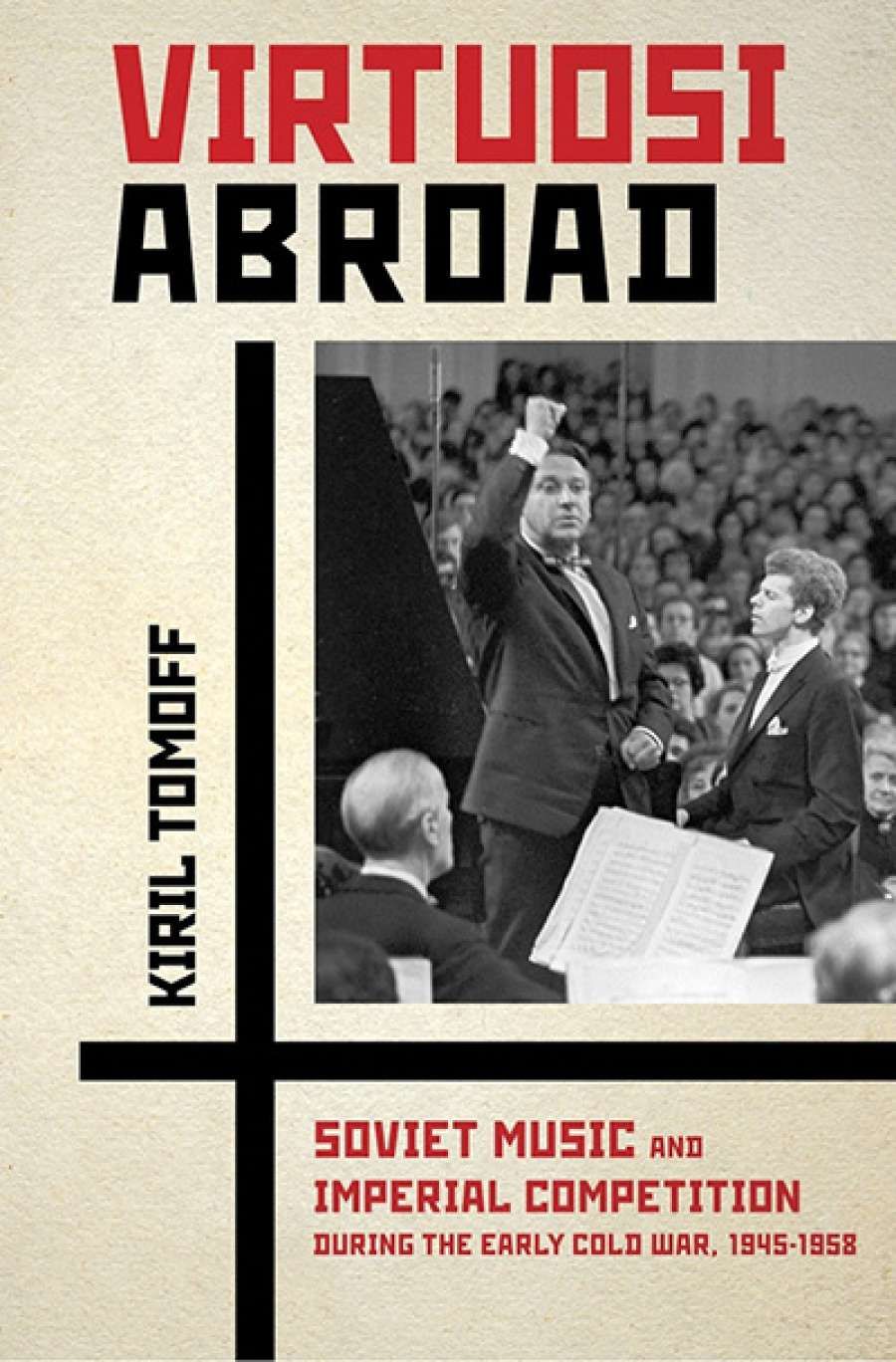

- Book 1 Title: Virtuosi Abroad

- Book 1 Subtitle: Soviet music and imperial competition during the early Cold War, 1945–1958

- Book 1 Biblio: Cornell University Press (Footprint) $83 hb, 256 pp, 9780801453120

Soviet musicians kept winning the international competitions when they resumed after World War II. The Soviet violinist Nelli Shkolnikova, who was later to spend many years in Australia, was the victor at the Long-Thibaud Competition in France in 1953. But there was one competition they famously didn’t win: the first International Tchaikovsky Competition, held in Moscow in 1958, which was won by the American Van Cliburn, who made a tremendous hit with Soviet audiences. Rumour has it that this was so big a problem for the Soviet authorities that Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s personal approval had to be obtained, but on the basis of the archives Tomoff shows that this wasn’t so. The Soviets were actually quite pleased to give the piano prize to an American, and thus show how non-parochial they were; what slightly embarrassed them was that Soviet violinists had walked away with all the prizes in the violin section. But that’s not to say that, on other people’s turf, winning wasn’t extremely important to them. Even in the Van Cliburn case, they claimed a victory for the Russian school of piano playing, pointing out that his teacher, Rosina Lhévinne at the Julliard School in New York, had been a graduate of the Moscow Conservatory class of Vasily Safonov before the revolution.

An Australian tour for Oistrakh was first mooted in the summer of 1955, when John Rodgers, secretary of the Australia-Soviet Friendship Society, who was close to, if not a member of, the Australian Communist Party, contacted a Soviet cultural agency to convey the ABC’s interest in inviting Oistrakh to perform in Melbourne, Sydney, and Adelaide the next year. That didn’t come off, but when Oistrakh finally did come in 1959, Rodgers and his wife hosted a reception for three hundred guests. It’s a slightly ambiguous story, though, because it’s not clear whether it was Rodgers’s leftist credentials or his entrepreneurial vigour that brought him into the picture. On top of that, as Tomoff notes in a footnote citing Phillip Deery, some have suggested that Rodgers was actually an ASIO agent.

Music was the part of the great Cold War competition with the United States that the Soviets undeniably won, at least in the 1950s. Their performers won laurels wherever they went. Even Dmitri Shostakovich and Sergei Prokofiev, in the long run, won the competition for the hearts of international concert audiences over Americans Aaron Copland and Samuel Barber, not to mention high modernists like Milton Babbitt. In the 1950s there were no major Soviet artistic defections, although the Soviets kept some performers at home out of prudence, like the great pianist Sviatoslav Richter, whose mother was an emigrée and whose Soviet-German father had been shot by the Soviets during World War II. They worried about Richter, too, because they counted him as a bachelor, hence more likely to defect (he had, in fact, a long-time de facto wife, the singer Nina Dorliak, but the authorities’ refusal to acknowledge  David Oistrakh (Wikimedia Commons)her suggests that they had heard the rumours he was gay). Jews also felt discriminated against in the selection process for international competition and tours, although this did not prevent many Jewish performers, from David and Igor Oistrakh to Bella Davidovich and Nelli Shkolnikova, winning international competitions for the Soviet Union. ‘You send us your Jews from Odessa, and we send you ours’, was the joke about Soviet-American cultural exchange attributed to Isaac Stern.

David Oistrakh (Wikimedia Commons)her suggests that they had heard the rumours he was gay). Jews also felt discriminated against in the selection process for international competition and tours, although this did not prevent many Jewish performers, from David and Igor Oistrakh to Bella Davidovich and Nelli Shkolnikova, winning international competitions for the Soviet Union. ‘You send us your Jews from Odessa, and we send you ours’, was the joke about Soviet-American cultural exchange attributed to Isaac Stern.

In the mid-1970s things started to turn sour. The defection of the dancers Rudolf Nureyev and Mikhail Baryshnikov shifted the terms of the cultural public relations competition sharply against the Soviet Union. Finding herself largely banned from foreign tours, Shkolnikova defected to Berlin in 1982. Her first appointment in the West, on the invitation of John Hopkins, was to teach in Melbourne at the Victorian College of the Arts. Other Soviet performers continued to tour and impress international audiences, but the magic was gone. The Soviet Union was still seen in the West as producing the greatest musicians and dancers. But it was also seen as alienating them because it was such an awful place in which to live and yet it endeavoured to strong-arm them into staying.

Comments powered by CComment