- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Law

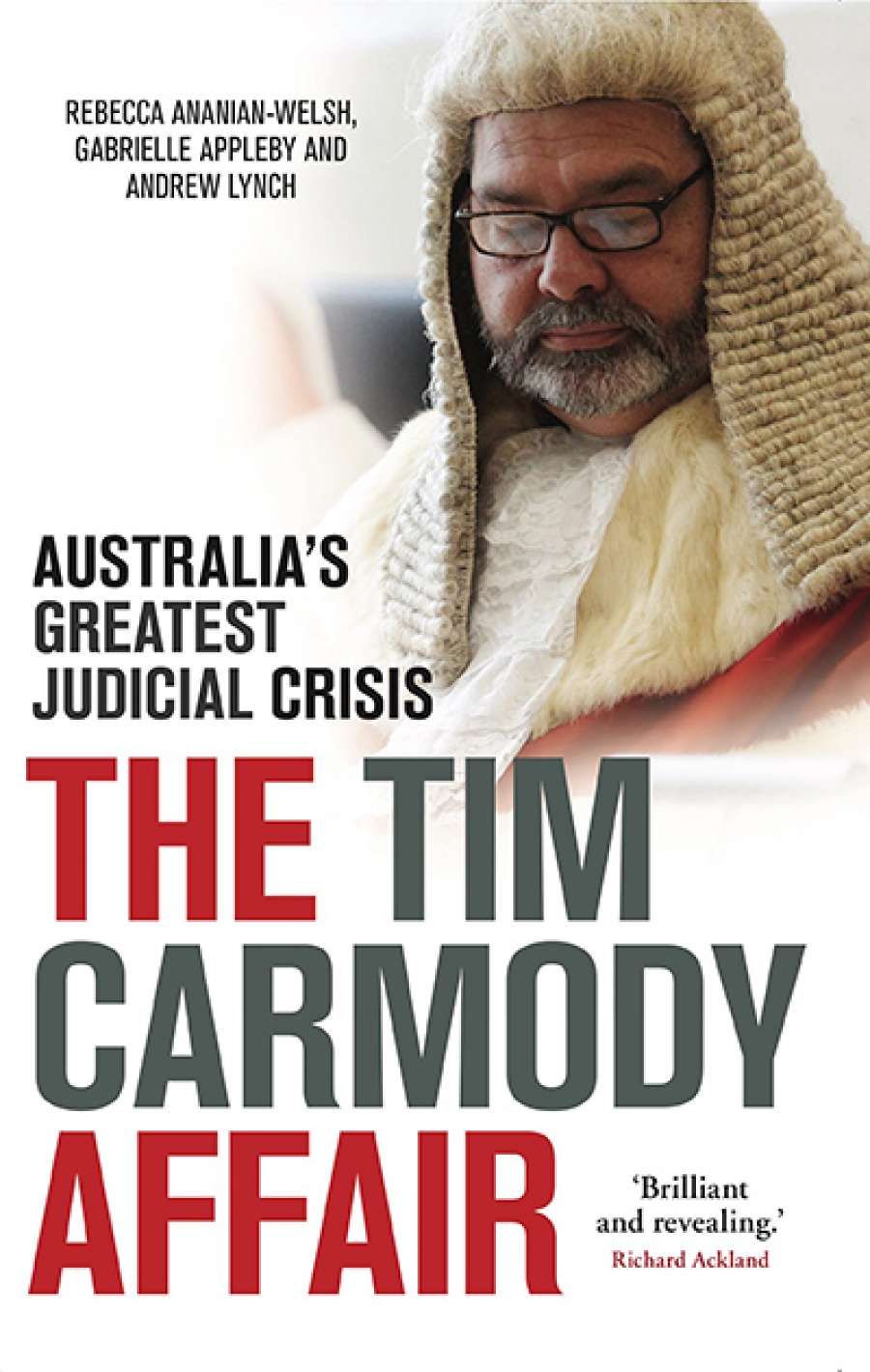

- Custom Article Title: David Rolph reviews 'The Tim Carmody Affair: Australia’s greatest judical crisis' by Rebecca Ananian-Welsh, Gabrielle Appleby, and Andrew Lynch

- Custom Highlight Text:

With a few notable exceptions (Michael Kirby springs to mind), judges in Australia do not have a high public profile. Many non-lawyers would struggle to name a judge currently ...

- Book 1 Title: The Tim Carmody Affair

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australia’s greatest judical crisis

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth $29.99 pb, 245 pp, 9781742234991

The lack of public profile for judges starts from the time of their appointment and, for most of them, continues throughout their time on the bench. Judicial appointments in Australia are barely newsworthy and rarely controversial. There will be a press release from the attorney-general, a mention in an email newsletter from the bar association or the law society, sometimes even a short item in a newspaper. Notwithstanding the importance of the judiciary as a branch of government and as an upholder of the rule of law, most judicial appointments go largely unheralded.

The appointment of Tim Carmody as the chief justice of Queensland in July 2014 by Campbell Newman’s Liberal National Party government was different. It gave a number of Queensland judges, not only Tim Carmody, a public profile. It also drew public attention to the usually opaque process of judicial appointments.

Carmody replaced the long-serving Paul de Jersey, who had been appointed as governor of Queensland. At the time of his appointment, Carmody had been chief magistrate of Queensland for a little over nine months. Although Carmody had been a Family Court judge for approximately five years, there was a perception that he was too inexperienced to take the job at the apex of the administration of justice in Queensland. There was also a perception, based particularly on Carmody’s actions and statements in support of the tough anti-outlaw motorcycle gang legislation, that Carmody was too politically aligned with the Newman government. For justice to be administered properly by an independent judiciary, perceptions matter.

Despite (or perhaps because) of the resistance shown by significant sections of the judiciary and the legal profession, Newman proceeded with Carmody’s appointment. It quickly became apparent that Carmody was unable to command the confidence and respect of the judges with whom he had to work on the Supreme Court. In under a year, Carmody had resigned his post.

The Carmody Affair documents in meticulous detail the appointment of Carmody, his tumultuous tenure as chief justice, his resignation, and its aftermath. Written by three legal academics, one from the University of Queensland and two from the University of New South Wales, it is a thorough and accessible account of this important episode in recent Queensland history, and of judicial politics more generally. The subtitle of the book, ‘Australia’s Greatest Judicial Crisis’, may overstate the importance of the Carmody affair. It may be the latest, but can it really claim to be the greatest? The travails of Lionel Murphy may have a justifiable claim to that title. There is no doubt, though, that the Carmody affair raises important questions about the relationship between law and politics in Australia, which are thoughtfully canvased in this book.

As the authors acknowledge, the Carmody affair is a particularly Queensland one. The controversy is in part explicable only against the backdrop of the Newman government. Coming to power in an electoral landslide, Campbell ‘Can Do’ Newman set about shaking things up after more than a decade of Labor regimes. Without the impediment of an upper house, Newman had few restraints. The Carmody affair in turn triggered a deeper, underlying anxiety about the potential for debasing public institutions in Queensland. It raised concerns about a return to the Bjelke-Petersen style of government. In this context, it was no surprise that Tony Fitzgerald, Chair of the Commission of Inquiry into Official Corruption in Queensland in the late 1980s, emerged as a critic of the appointment of Carmody as chief justice.

As the authors equally suggest, the Carmody affair raises broader questions of relevance throughout Australia. Perhaps the most significant one relates to the process of judicial appointments, which is at the heart of the Carmody affair. Unlike other legal systems in the English-speaking world, which have a variety of mechanisms for appointing, recommending, or exercising oversight over the appointment of judges, Australia, at a federal, state, and territory level, still allows the executive a wide, largely unfettered discretion in making judicial appointments. This approach often works well, as is demonstrated by the many uncontroversial judicial appointments it has produced. When things go wrong, however, the risks associated with placing the decision in the hands of so few become apparent. Once appointed, it is difficult to remove a judge. There is good reason for this. The independence of the judiciary is a vital feature of our system of government. Removing a judge should not be made easier. The solution is to ensure a rigorous appointment process. As the authors of The Carmody Affair point out, this is an important matter of public policy which requires further consideration in Australia.

Comments powered by CComment