- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Indigenous Studies

- Custom Article Title: Timothy Neale reviews 'A Handful of Sand: The Gurindji struggle, after the walk-off' by Charlie Ward

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

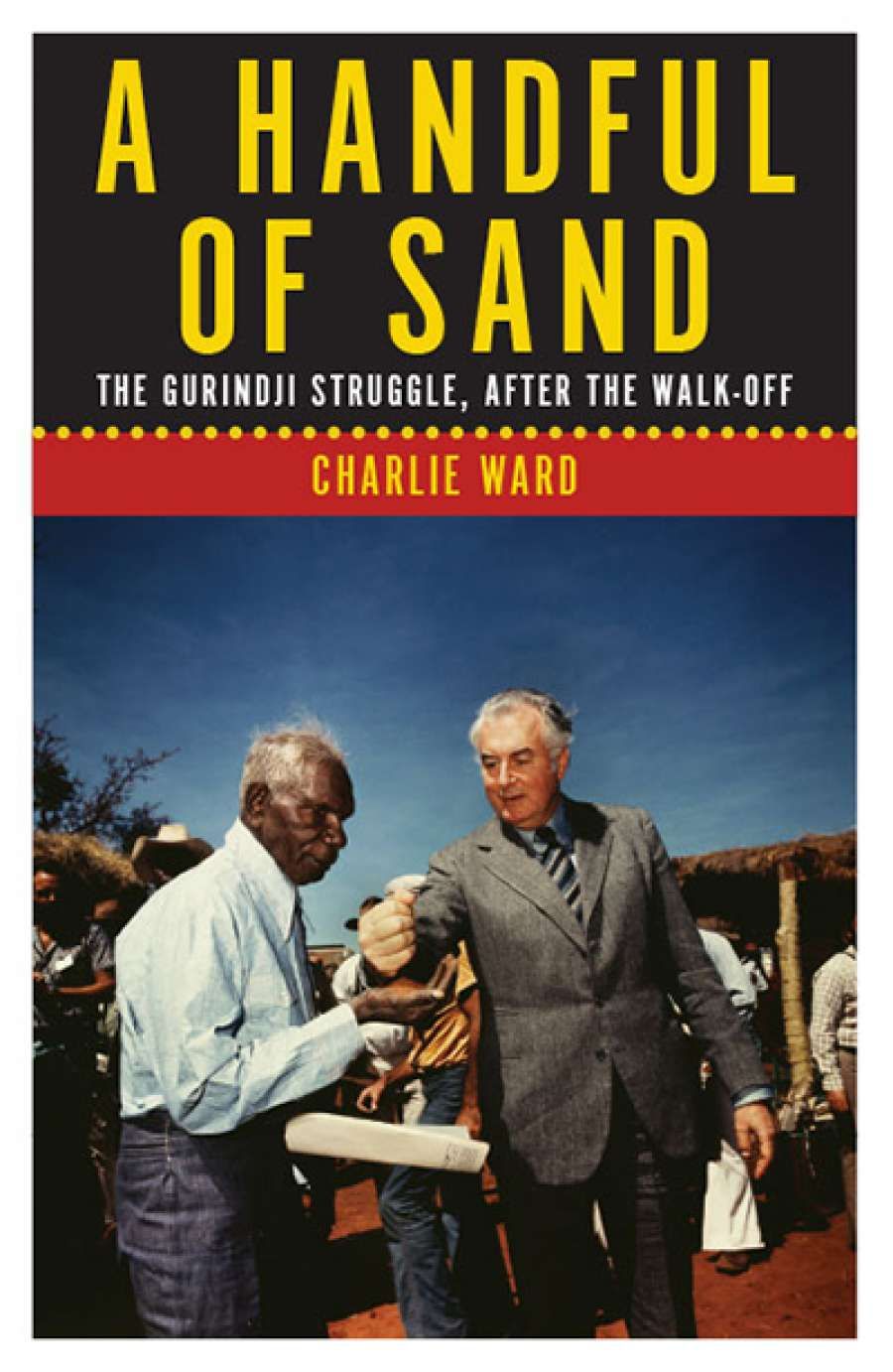

The iconography of Indigenous land rights in Australia is fundamentally deceptive. Take, for example, the famous photograph of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam pouring red ...

- Book 1 Title: A Handful of Sand

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Gurindji struggle, after the walk-off

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $29.95 pb, 384 pp, 97819253771613

While the accepted meaning of the handover, then as now, is that it represented a victory for land rights, Charlie Ward suggests in A Handful of Sand that it was ‘anything but’. This is at least true, Ward argues, for the Gurindji and their ngumpit countrymen living at Kalkaringi, the former Wave Hill Welfare Settlement, and Daguragu, the place on Wattie Creek where the ‘track mob’ led by Lingiari and others chose to settle after walking off a nearby pastoral station in 1966. What the Gurindji received after years of struggle, rallying support from across the country, was not possession, in any strong sense, but rather a pastoral lease and soft promises that freehold title was coming. The lease fulfilled some of the track mob’s aspirations by providing the basis for their own pastoral business. However, as Ward details, the lease and other land rights that followed also came with an abundance of legal apertures through which federal and (later) Northern Territory governments could exercise control.

The handover image thus actually encodes a pair of myths central to Indigenous politics in Australia, or what might more accurately be called the whitefella politics of Indigenous country. The first myth is that Indigenous people were given control of their communities through the ‘self-determination’ and ‘self-management’ policies of the Whitlam and Fraser governments. Instead, as Ward shows, these administrations ironically established, equipped, and supported an army of variously well-intentioned and opportunistic kartiya (outsiders, settlers, whitefellas) to administer the project of Indigenous independence. The second myth is that Indigenous people have substantial legal property rights. Decades of fearmongering by the timorous pastoral and mining sectors, buoyed by conservatives such as Joh Bjelke-Petersen and John Howard, have helped obscure the fact that since colonisation, Indigenous people have never held their soil, or the minerals under that soil, in exclusive possession. None of the manifold forms of Indigenous land rights in Australia – from South Australia’s Aboriginal Lands Trust Act 1966 to Victoria’s Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010 – offers what Whitlam’s words and actions suggested on Gurindji country that sunny day in 1975.

Ward takes us to this broader view by focusing on both the Gurindji’s long quest for independence and the disappointments that followed in the decade after the handback. Drawing on archival research and interviews with many of the Indigenous and non-Indigenous actors in this story, he seeks to understand the shifting motivations at work and their effects on the realisation of the track mob’s aspirations. In this sense, the book is more interested in personalities than in structures or academic analyses of policy. Events are marked by interpersonal exchanges, taking us up close to members of the track mob such as Lingiari, Captain Major Lupngiari, and Mick Rangiari, labour organisers such as Dexter and Davis Daniels, and the kartiya at Daguragu and Kalkaringi such as Philip Nitschke and Rob Wesley-Smith, among others.

Gough Whitlam and Gurindji men, 16 August 1975 (Courtesy of Rob Wesley-Smith)This arguably makes Ward’s book an account of Wave Hill alone, though an account in which we can nonetheless espy familiar political rhythms being played out and sedimented. First, an Indigenous group subject to gross inequity takes bold action to embarrass the settler colonial state. Soon, commercial stakeholders – in this case the British pastoral giant Vestey’s – who have long profited from this inequity deny culpability and deploy lobbyists to quietly secure their interests, while government actors find obscure reasons to delay. Others are rallied to support the Indigenous group and expand the embarrassment of the state. Policy reviews are commissioned, and advice taken, until a legislative option emerges that instantiates a new inequity, albeit one cloaked in a miasma of optimism. Exhausted by this process, and unable to recruit the next generation to their worldview, Ward argues that the track mob became desperately resigned two decades after the walk off.

Gough Whitlam and Gurindji men, 16 August 1975 (Courtesy of Rob Wesley-Smith)This arguably makes Ward’s book an account of Wave Hill alone, though an account in which we can nonetheless espy familiar political rhythms being played out and sedimented. First, an Indigenous group subject to gross inequity takes bold action to embarrass the settler colonial state. Soon, commercial stakeholders – in this case the British pastoral giant Vestey’s – who have long profited from this inequity deny culpability and deploy lobbyists to quietly secure their interests, while government actors find obscure reasons to delay. Others are rallied to support the Indigenous group and expand the embarrassment of the state. Policy reviews are commissioned, and advice taken, until a legislative option emerges that instantiates a new inequity, albeit one cloaked in a miasma of optimism. Exhausted by this process, and unable to recruit the next generation to their worldview, Ward argues that the track mob became desperately resigned two decades after the walk off.

A Handful of Sand is both a celebration and critique of the Gurindji struggle, grounded in the author’s long engagement with the community. Like others before him, Ward is clear in pointing out that the frontier pastoral model pursued by Lingiari and others was not sustainable, though he does not blame the Gurindji for the station’s eventual demise. Perhaps the greatest contribution of the book is not its compelling retelling of the famous walk off, or the handover, but its documentation of the creeping effects of policy, at a personal level, on those who grappled with the Whitlam and Fraser bureaucracies. In these later chapters, we can see the political project of independence being turned into the later project of coercive improvement, measured out in ‘gaps’ and ‘jobs’. Nonetheless, Ward evokes a hopeful note in closing. The abiding image of Wave Hill should be ‘Lingiari’s legacy’, which he detects in the resilience of contemporary Gurindji leaders, rather than something as insubstantial and ephemeral Whitlam’s handful of sand.

Comments powered by CComment