- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Custom Article Title: Anwen Crawford reviews '1966: The year the decade exploded' and 'England’s Dreaming: Sex Pistols and punk rock' by Jon Savage

- Custom Highlight Text:

In March of 1966, Los Angeles rock group The Byrds released their sixth single, a song called 'Eight Miles High'. It was, writes Jon Savage, a song that combined 'two staples of sixties ...

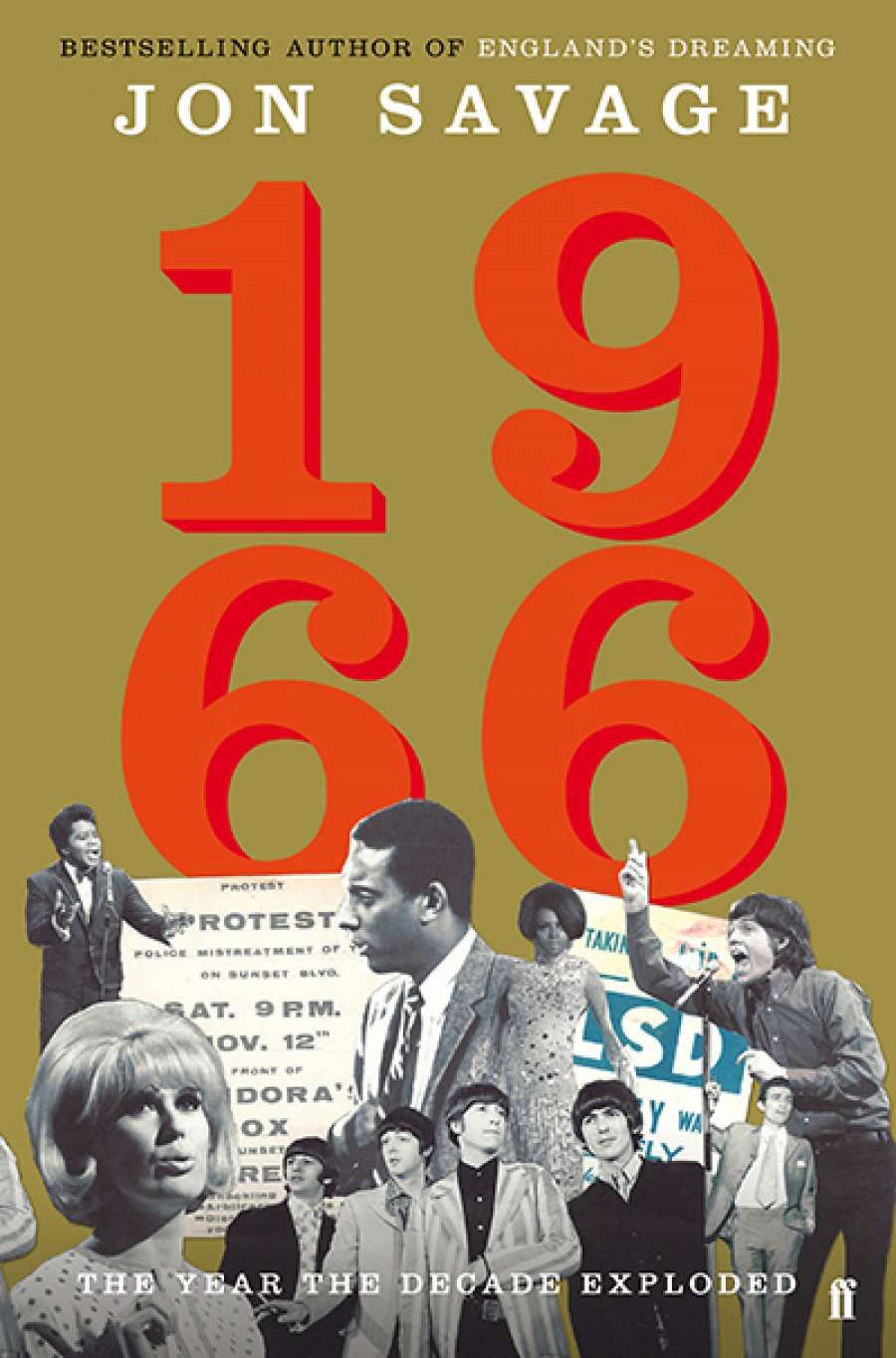

- Book 1 Title: 1966

- Book 1 Subtitle: The year the decade exploded

- Book 1 Biblio: Faber, $49.99 hb, 653 pp, 9780571277629

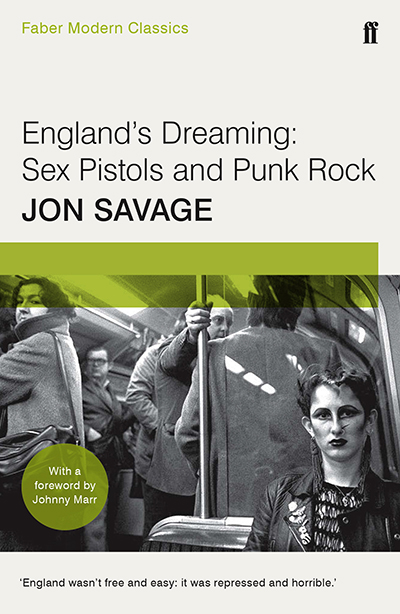

- Book 2 Title: England’s Dreaming

- Book 2 Subtitle: Sex Pistols and punk rock

- Book 2 Biblio: Faber, $12.99 pb, 653 pp, 9780571326280

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Online_2016/October_2016/ENGLANDS%20DREAMING400px.jpeg

Savage is a respected music critic and historian. English-born, he began his career in the 1970s as a journalist for the British weekly music paper Sounds. He has demonstrated a sustained interest in youth culture (his previous book, Teenage, published in 2007, was a history of adolescence during the first half of the twentieth century), and he is able to tease out the social and political ramifications of that culture. 1966 proceeds month by month through the year, in twelve chapters, with each chapter framed by discussion of a 45RPM single. Some songs released that year, like The Four Tops's '(Reach Out) I'll Be There', remain in the public consciousness to this day. Others, like 'A Quiet Explosion', by Birmingham rock group The Ugly's, swiftly disappeared. In all of them Savage hears a fervency that spoke to the times.

Popular music in 1966 was characterised by the tension between mass popularity and a burgeoning underground. Some artists, like The Beatles, were caught between these territories. John Lennon caused controversy when comments he made to the Evening Standard about The Beatles being 'more popular than Jesus' hit American newsstands in late July. Soon afterwards, the band's seventh studio album, Revolver, was released: the closing track, 'Tomorrow Never Knows', was another early landmark of psychedelia. Savage describes it as 'a mass market avant-garde artefact', one that combined advanced studio techniques, such as tape loops, with the counter-cultural imperative to 'be here now'. But this commitment to living in the present – also expressed throughout the year in an increasing number of 'happenings' and immersive art environments – was edged by nihilism. The working title for 'Tomorrow Never Knows' was 'The Void', and who knew what might happen if you looked into it.

Most extreme were The Velvet Underground, who, in 1966, became the house band at Andy Warhol's Factory. Their songs dealt with topics – heroin addiction, sadomasochism – that were challenging even by the standards of the time, and their type of New York decadence was received with hostility when they toured the West Coast as part of Warhol's multimedia performance nights, which were known as the Exploding Plastic Inevitable. 'They will replace nothing, except maybe suicide,' said Cher. John Cale, one of The Velvet Underground's members, summarised the group's attitude: 'We hated everybody and everything.'

The Velvet Underground would go on to have an enormous, and enduring, influence on rock music, but their spirit of confrontation – and the bleak, harsh sound of their early records – had an especial impact on punk. That outbreak of musical and social upheaval is the subject of Savage's book England's Dreaming: Sex Pistols and Punk Rock, first published in 1991, and reissued this year as a Faber Modern Classic.

England's Dreaming has been acclaimed, in the decades since its initial publication, as the definitive book on punk – certainly on British punk – and for good reason. It is an exhaustive treatment, based on interviews that Savage conducted with many of punk's main figures, and given momentum by a detailed narrative of the Sex Pistols, whose short and turbulent existence would permanently alter the possibilities of popular culture. The Sex Pistols brought into being a genuine opposition to mainstream consensus in Britain, their songs and performances shaped by virulent rage; but they were also a kind of prank, staged for maximum controversy by their manager, Malcolm McLaren. England's Dreaming is, among other things, the story of how McLaren and John Lydon – who was known as Johnny Rotten during his time as the Sex Pistols' vocalist – began by mirroring each other's ambitions but came to despise one another, riven by the irresolvable contradictions of their joint project.

The Sex Pistols, Johnny Rotten and Steve Jones in Amsterdam, 1977 (ANEFO, Wikimedia Commons)

The Sex Pistols, Johnny Rotten and Steve Jones in Amsterdam, 1977 (ANEFO, Wikimedia Commons)

'One definition of nihilism,' writes Savage, 'is that it is not the negative or cynical rejection of belief but the positive courage to live without it.' For a brief time, the Sex Pistols and their followers – many of whom would form groups of their own, when the barrier of even basic musical competence was demolished – would attempt to live outside of existing social conventions. Their rebellion was of a different tenor to the bohemians who had proceeded them. 'No future for you,' warned John Lydon in 1977, which was not quite the same as John Lennon singing 'Turn off your mind' in 1966. A sense of desperate and terminal violence hung in the air; in Germany that year, members of the Red Army Faction murdered judges and kidnapped politicians. If this was the legacy of 1960s utopianism, it was a poisoned one. Short extracts from Savage's contemporaneous diaries, written when he was a young journalist, capture the mood, and also the violence directed against punks themselves: 'the result is a claustrophobia so tight that you can barely speak'.

England's Dreaming ranges over a wider span of time than 1966, but it is the more focused of the two books, and the more original. Though 1966 sets out to cover one year in detail, it soon becomes a more general history of the decade and its music. England's Dreaming digs deeper into the cultural and political impulses that would form punk, and which the movement, in turn, gave expression to. In absenting themselves from moral norms, punks could voice desires that still sound both unsettling and prescient. 'Give me World War Three, we can live again,' sang Lydon. He didn't mean it – or did he?

Comments powered by CComment