- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

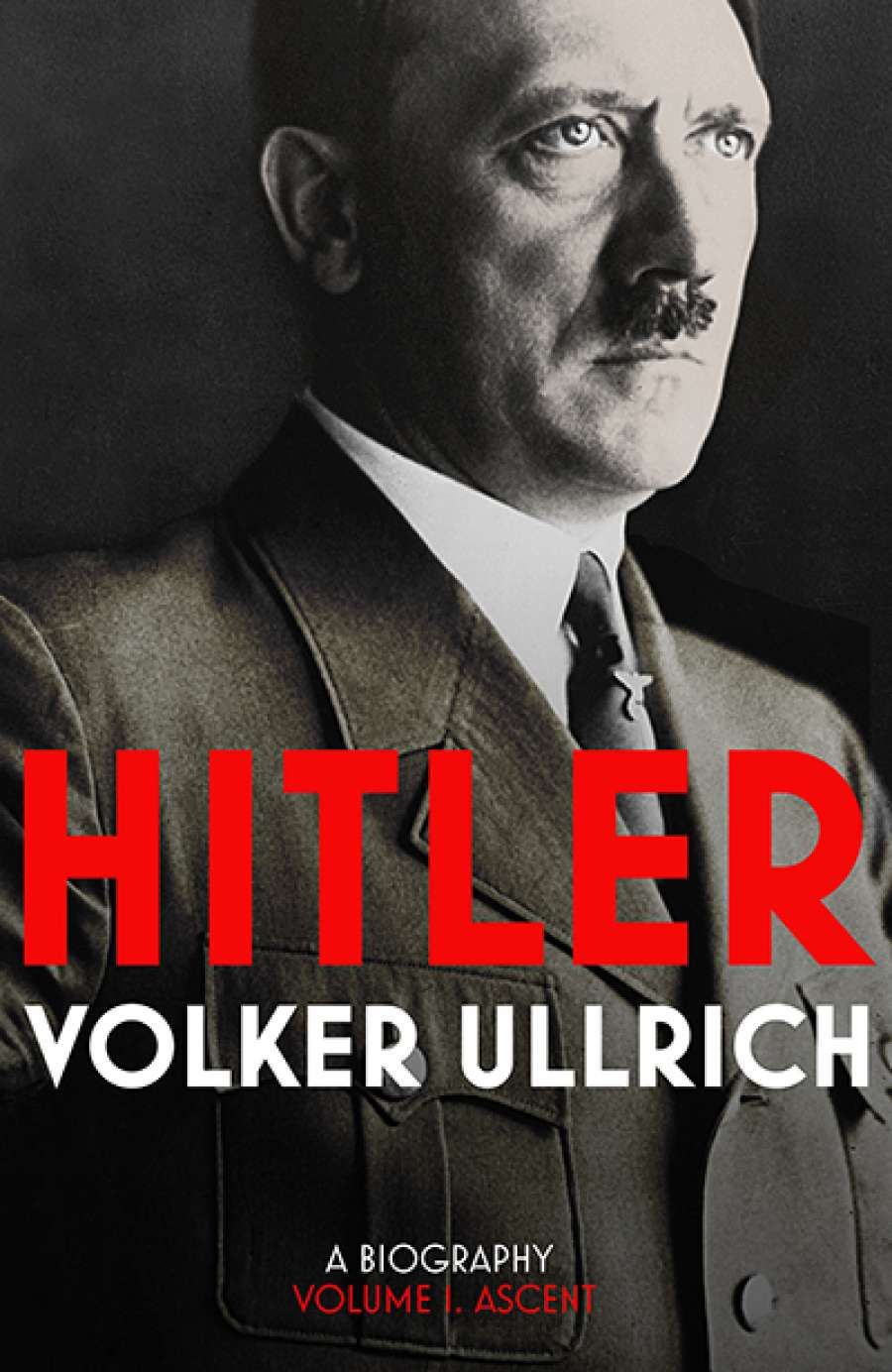

- Custom Article Title: Miriam Cosic reviews 'Hitler: A biography, volume I: Ascent, 1889–1939' by Volker Ullrich and translated by Jefferson Chase

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There is a point of view that says we shouldn't humanise a tyrant such as Adolf Hitler since that reduces the symbolism, the power of his name as a synonym for pure evil, and can lead to ...

- Book 1 Title: Hitler: A Biography

- Book 1 Subtitle: Volume I: Ascent, 1889–1939

- Book 1 Biblio: Bodley Head, $59.99 pb, 998 pp, 9781847922861

Well, yes, it turns out. Volker Ullrich's massive tome – 1,000 pages and it is only part one of two – is a welcome addition to the bookshelves. Hitler: A biography, volume I: ascent, 1889–1939 provides little that is startlingly new, though the opening up of East Germany's archives after 1989 has provided additional material unavailable to Western postwar scholars. What Ullrich has managed to do, however, is re-craft the history compellingly for our own era. His scholarly rigour, very readable prose (thank you, too, translator Jefferson Chase), and clear argument are leavened by a fascinating amount of personal detail, from Hitler's unremarkable childhood through the loneliness and, presumably, deep depression of his late adolescence, to his galvanising experience during World War I and his relentless rise to prominence on the German right. Most frightening are the parallels one can draw to the backlash against multiculturalism and rise of populism across the West today.

Hitler liked to claim that he grew up in poverty, but his father was a senior public servant and earned a middle-class salary. He had a happy enough younger childhood in southern Bavaria, where his father had been transferred from Austria and where he picked up his accent, doing well in school and reading westerns in his spare time. (He was a fan of Karl May, and would even refer back admiringly to his characters during the war.) His father was authoritarian; his mother quiet and protective. Ullrich points out that historians' assumption that his father's violence towards him was formative overlooks the fact that corporal punishment was normal in families at the time and no one else turned out quite like little Adolf. 'If Hitler had a problem,' he writes, 'it was an overabundance rather than a paucity of motherly love. That may have contributed to his exaggerated self-confidence, his tendency towards being a know-it-all and his disinclination to exert himself in areas he found unpleasant. These characteristics were already evident during Hitler's school days.'

The transition to high school in well-to-do Linz, back in Austria when his father retired, was not so congenial. Hitler was tormented by his classmates for being a country yokel. A teacher remembered him as talented but lazy. 'As he entered puberty,' Ullrich writes, 'the lively, curious young boy became an introverted, moody adolescent who positioned himself as an outsider.' His father died suddenly in 1903, his mother four years later, aged forty-seven. Hitler, who was eighteen, tended to her assiduously at the end. Not long before her death he sat the entrance exam of the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and was astonished when he failed, something he kept secret from everyone.

In early 1908 he left for the sophistication of ethnically diverse Vienna. He seemed to learn little there. His art was certainly not influenced by Viennese modernism, something that played out horribly in the burning of 'degenerate' art when he came to power. Unable to find a foothold in the city, he ended up in a shelter for homeless men, selling painted postcards on the street. Ullrich maintains that Hitler had not been anti-Semitic when he arrived in Vienna; indeed, he continued to revere his mother's Jewish doctor. But he would have been exposed to organised right-wing groups there. A small inheritance allowed him to move to Munich, where he eventually found his milieu.

The turning point was World War I. Although many people across Europe looked forward to the 'cleansing' advent of war in the decadent and unstable early years of the twentieth century, most were quickly disillusioned by the horrors of mechanised fighting. His participation made Hitler, however. Having first been turned down by the army on health grounds, he eventually enlisted and had a solid career as a communications runner, earning the Iron Cross. He also experienced the warmth of membership for the first time – previously, Ullrich points out, '[his] lack of social contact was the external symptom of a deep inner uncertainty' – and was still ensconced in the military, and used it as a launch pad, when he began to expand the National Socialist Workers Party. It was, of course, neither socialist nor a worker's party, though Hitler grew adept at playing on both these tropes as he developed his one real talent: for rabble-rousing speechifying.

German soldiers during World War I, Adolf Hitler at left (Wikimedia Commons)

German soldiers during World War I, Adolf Hitler at left (Wikimedia Commons)

Kershaw described Hitler as an 'empty vessel outside his political life', incapable of the intimacy of sexual love or friendship. As Neal Ascherson wrote in his review of Ullrich in the London Review of Books, 'He [Kershaw] considered that Hitler had no "private life", but instead "privatised" the public sphere: his entire career was devoted to acting the Führer.' Ullrich cautions against overplaying this point. Hitler may or may not have had a sexual relationship with Eva Braun, but they certainly had a domestic one. He suffered terribly when his niece, Geli Raubal, committed suicide while living with him, and continued to visit her grave even when in power. He loved Wagner's operas and was a regular, and fêted, guest at Bayreuth. Older women doted on him, as a leader and as a single man in need of cosseting, and he rewarded them with exaggerated Viennese chivalry.

Ullrich shows that he was never at ease in the higher echelons of society, however, nor with his intellectual superiors. 'As is typical for many autodidacts, Hitler believed he knew better than specialists ... and treated them with an arrogance that was but the reverse of his own limited horizons,' he writes. 'As a parvenu, Hitler lived in constant fear of not being taken seriously or, even worse, making himself look ridiculous.' He was decidedly quirky in so many ways: a vegetarian non-smoker, he doted on dogs, couldn't dance, drive, or ski, and had no interest in acquiring those skills.

Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun with their dogs at the Berghof, Germany (Wikimedia Commons)

Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun with their dogs at the Berghof, Germany (Wikimedia Commons)

Hitler was entirely at home in politics, however. Under his leadership the party expanded quickly. Within a year, meetings had expanded from a couple of dozen to 2,000-strong cheering fellow travellers. Hitler had only two defining policies: removal of the Jewish influence he believed was ruining the entire Western world, and extension of Lebensraum – space for the German people to live – into eastern Europe. All the rest was tactics. Hitler alternated between calm persuasion and dramatic threats, first in his inner circle, then with German and Austrian politicians, eventually with world leaders. Although apparently tortured by decision-making, he took careful and unerring steps towards legal implementation of his plans, gauging exactly how far he could push each one without causing a backlash.

At the end of this volume, these steps culminate in the Anschluss, the move on Czechoslovakia, and the absurdly lavish public celebrations of Hitler's fiftieth birthday. Despite the enormous amount of detail, Volker Ullrich traces them with pace and vigour.

Comments powered by CComment