- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

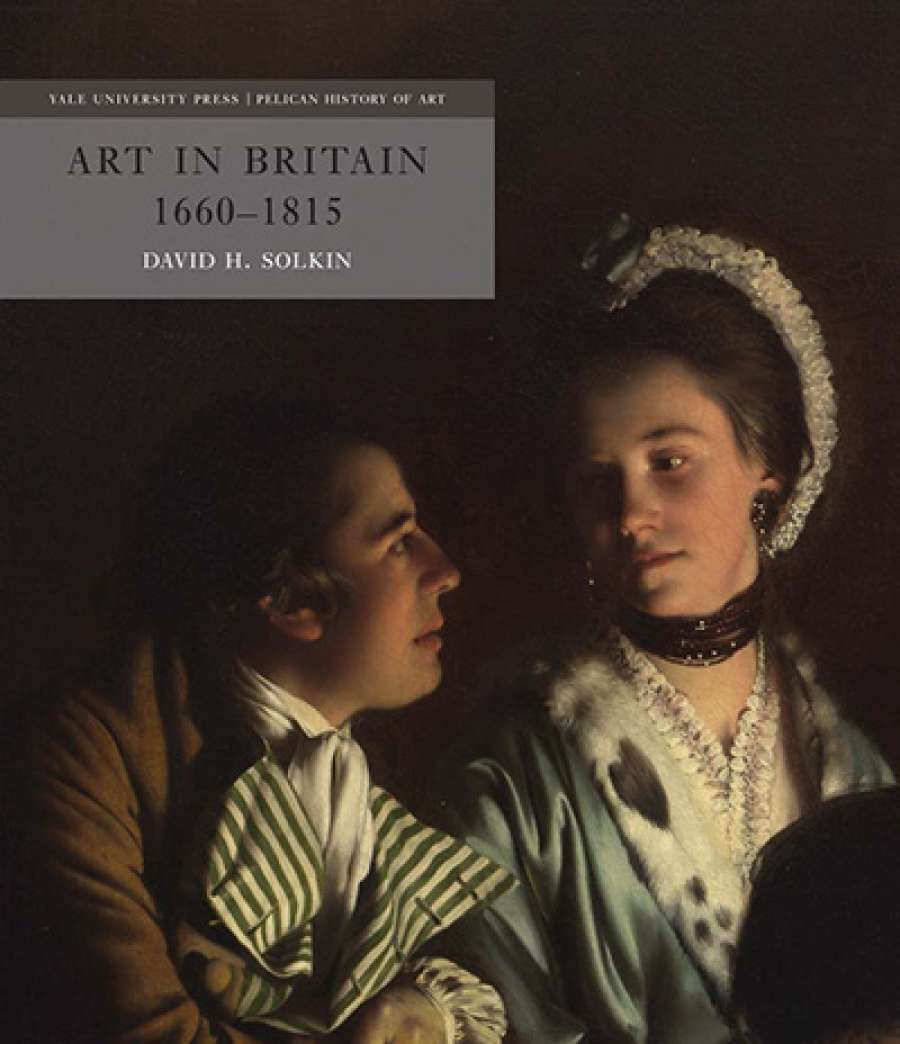

- Custom Article Title: Patrick McCaughey reviews 'Art in Britain 1660–1815' by David H. Solkin

- Custom Highlight Text:

A major revolution swept through British art history in the 1980s. It shook up its genteel ways and turned it resolutely, even militantly, towards the social history of art ...

- Book 1 Title: Art in Britain 1660–1815

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press (Footprint) $119 hb, 384 pp, 9780300215564

Solkin ruefully acknowledges his past, noting with gratitude that John Nicoll, then the editor of Yale University Press in London, commissioned the present work over twenty years ago from 'a relatively young and not uncontroversial scholar'. Art in Britain 1660–1815 was to replace Ellis Waterhouse's Painting in Britain 1530–1790 (1953), the first volume of the massive Pelican History of Art. Waterhouse did not belong to the genteel tradition, but his Pelican History was numbingly dull. It must have turned more students off British art than those rooms of English divines in the old National Portrait Gallery.

Solkin introduces his intentions unapologetically. He has selected artists and objects for 'their ability to illuminate ... the most significant historical trends, and not because they have secured the aesthetic endorsement of posterity'. He embraces those ungainly Graces of the 'new' art history: class, gender, and race. It is 'the art historian's first duty ... to produce critical analysis of how visual culture has operated within a social field structured by relationships of power'.

Happily, the book escapes from these grim and joyless strictures. Throughout a densely argued text, it remains an object-orientated history. Solkin has an eye for the unfamiliar but telling work such as Francis Hayman's See-Saw to exemplify the ambiguous pleasures of Vauxhall Gardens – romantic assignations to the strains of Handel. Hayman's painting was part of the Vauxhall decorations and shows a young girl tumbling off the bottom of the see-saw into the 'rescuing' hands of an over-eager youth. A scruffy tough, suspended at the high end of the see-saw desperately flails his arms to keep his balance. A third youth dashes into the scene, fist at the ready. It mirrors perfectly a state of 'playful anarchy', reminiscent of Alexander Pope's famous antinomy of 'the frail china jar' and 'the rude hand of chaos'. The complementary institution in London was the Foundling Hospital for the homeless and unwanted children of the capital. Established in 1739 by Captain Thomas Coram, it was an action equal in philanthropy and enlightenment. William Hogarth was a devoted early contributor. Solkin's account of the institution and the support it generated among the leading artists of the day is nimble and instructive. How completely fitting that he reproduces, full page, Hogarth's portrait of Coram, wigless but majestic, kindly and welcoming, one of the foremost humanist portraits of the age.

See-Saw (1748), Francis Hayman (1708-1766) oil on canvas (Tate Gallery)

See-Saw (1748), Francis Hayman (1708-1766) oil on canvas (Tate Gallery)

Portraiture looms large in Solkin's account. The genre marks the occasion when the artists and the ruling élite shook hands on a contract of mutual benefit: money for the artist and status, even fame, for the sitter. There is a chapter on portraiture in each of the five lengthy sections, as there is for a growing interest in nature and an evolving market for landscape painting. These five sections, each covering three to four decades, make for an authoritative, enveloping structure. You feel the change and expansion of the British art world over the eighteenth century. Solkin refuses to make artist's careers the basic unit of his history (no 'parade of individual "great" male artists'), but it means that many artists have their histories broken up and spread across different sections. Richard Wilson appears first on the Roman Campagna, but many moons and over seventy pages go by before we meet him again in London and Wales, the first British artist to paint 'the wild' and the Arcadian.

The biggest casualties of Solkin's approach are two of the period's most original artists: George Stubbs and Joseph Wright of Derby. We have little sense of the range or evolution of their art. Wright's portraiture, one of the most distinctive in an age of portraiture, is represented solely by Brooke Boothby, reclining in a damp English wood, clutching his Jean-Jacques Rousseau MSS, keeping his stylish but jauntily worn hat aloft. In this history, Stubbs and Wright of Derby come off as marginal figures – regrettably.

One wishes that Professor Solkin had strayed off the 'new' art history reservation more often and allowed himself to respond more freely to the superb anthology of works he has assembled. He can read pictures sensitively and insightfully. As well as being documents of power and commerce, eighteenth-century British pictures so often 'make the heart dance' in Gainsborough's unforgettable phrase. Could we not have been vouchsafed a bit more of that?

Comments powered by CComment