- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Custom Article Title: Philippa Hawker reviews 'Movie Journal: The rise of new American cinema 1959–1971' by Jonas Mekas

- Custom Highlight Text:

'Do you really want me to fall that low, to become a film critic, one of those people who write reviews?' asks Jonas Mekas, responding with typical brio to complaints ...

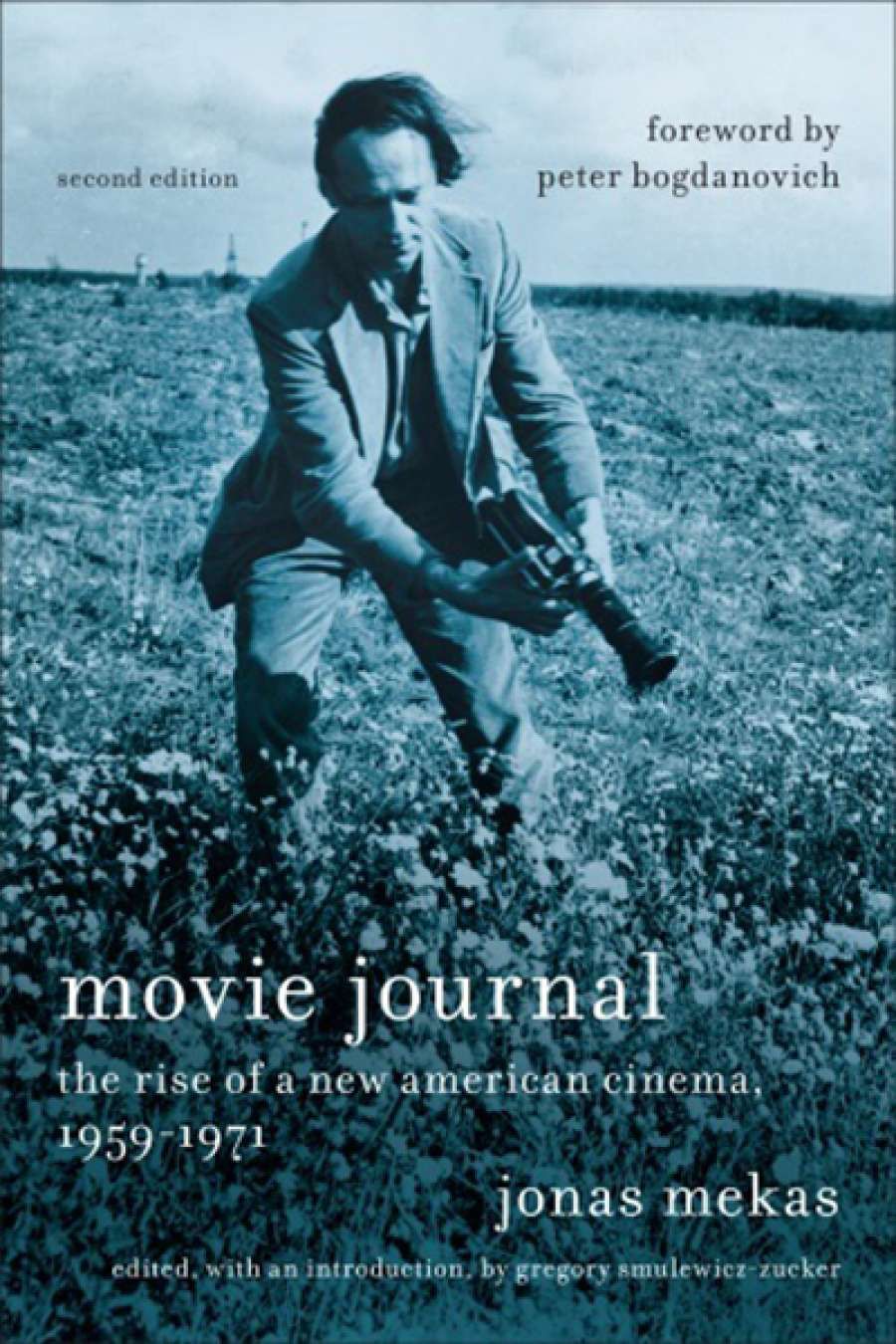

- Book 1 Title: Movie Journal

- Book 1 Subtitle: The rise of new American cinema 1959–1971

- Book 1 Biblio: Columbia University Press (Footprint), $59.95 pb, 453 pp, 9780231175579

Always proactive, Mekas virtually created the job himself. As he tells it, he went into the publication's office to ask why the Voice lacked a regular movie column. Associate editor Jerry Tallmer suggested he write one, and Mekas filed his first instalment the next day. He was already a busy figure in the New York cultural scene, chiefly as a filmmaker and founder of the journal Film Culture and the Filmmakers Co-operative; during his Voice tenure he also set up the Anthology Film Archives. Born in Lithuania in 1922, Mekas came to the United States in 1949, after spending time in work camps and refugee camps in Germany and briefly studying philosophy at the University of Mainz.

These days, the image of American film writing in the mainstream press of 1960s and 1970s focuses on Pauline Kael at the New Yorker dispatching Bosley Crowther of the New York Times then squaring off against Andrew Sarris of the Village Voice, US proponent of the auteur theory. Sarris and Mekas were colleagues in more than one publication: Sarris co-edited Film Culture with Mekas, but the two often had strong differences of opinion.

Mekas is conscious of writing in a different register from that of Kael or Sarris. For a short time, he tries on the critic's hat, but soon throws it away. 'It is not my business to tell you what it's about. My business is to get excited about it, to bring it to your attention. I am a raving maniac of the cinema,' he says. The column's title, 'Movie Journal' conveys the sense of a chronicle, a personal engagement. This takes many forms; he can write combative assessments, lyrical and visceral responses, brief notes, extended discussions, pieces of reportage. He conducts Q & A interviews, sends frontline dispatches, occasional pointed sallies against mainstream reviewers. He experiments with various ways of describing what he's seeing or experiencing, or drawing the reader into a debate. He set himself to be an advocate for a particular tendency in filmmaking, for the work that he called 'New Cinema', but also 'underground' and 'poetic' cinema. Some of the filmmakers he writes about – Andy Warhol, Maya Deren, Kenneth Anger, Shirley Clarke, Yoko Ono, Stan Brakhage, and Ken Jacobs – have become familiar even famous names. Others are less well-known, and Movie Journal becomes a valuable resource, a testimony to art and endeavour.

Mekas's own filmmaking revolves around the diary form, and his film writing has some of the same feeling. There is a sense of a creative life in action, across the spectrum of New York culture, ranging from a vivid account of an important, hastily conceived project to film a Living Theatre production called The Brig; to numerous examples of battles with censorship that he met as a filmmaker, distributor and viewer.

Jonas Mekas (photograph by Furio Detti, Wikimedia Commons)Yet from the beginning, the range of his interests is evident. There is a call for 'a derangement of cinematic senses'; a poetic evocation of a new Maya Deren work, The Very Eye of Night (1958); a furious denunciation of the distributor who dubbed Max Ophüls's Lola Montès and cut sixty-five minutes from it; a description of going to see the Rock Hudson–Doris Day comedy Pillow Talk (1959) in a posh new movie theatre with uncomfortable seats. He has a strong sense of immediacy, but he is writing for the future, and some of his dreams and predictions seem shrewd and prescient – not just about the movies but also about their context. 'Films will be soon be made as easily as written poems, and almost as cheaply. They will be made everywhere and by everybody', he wrote in October 1960. Four years later, he was imagining the means of circulation for these works. 'Soon you'll be able to buy prints of the films you like for three to five dollars for your own library, like books, like records, like tapes ... our films will be screened in every home.'

Jonas Mekas (photograph by Furio Detti, Wikimedia Commons)Yet from the beginning, the range of his interests is evident. There is a call for 'a derangement of cinematic senses'; a poetic evocation of a new Maya Deren work, The Very Eye of Night (1958); a furious denunciation of the distributor who dubbed Max Ophüls's Lola Montès and cut sixty-five minutes from it; a description of going to see the Rock Hudson–Doris Day comedy Pillow Talk (1959) in a posh new movie theatre with uncomfortable seats. He has a strong sense of immediacy, but he is writing for the future, and some of his dreams and predictions seem shrewd and prescient – not just about the movies but also about their context. 'Films will be soon be made as easily as written poems, and almost as cheaply. They will be made everywhere and by everybody', he wrote in October 1960. Four years later, he was imagining the means of circulation for these works. 'Soon you'll be able to buy prints of the films you like for three to five dollars for your own library, like books, like records, like tapes ... our films will be screened in every home.'

The editor of the second edition, Gregory Smulewicz-Zucker, writes an extended introduction with a biographical account of Mekas and an assessment of his critical position and its function. Mekas, he points out, is not a straightforward cheerleader for the avant garde. He can be a showman and a polemicist, and his positions and enthusiasms can be fluid and contradictory. He needs to be understood, Smulewicz-Zucker says, as a 'Romantic humanist' with a strong commitment to the value of culture.

'I have almost unlimited taste!' Mekas declared in the column in October 1962 addressed to readers who seemed to be suggesting that he wasn't a critic. Yet he is not talking about being uncritical or undiscriminating – he is referring to the breadth of his enthusiasms. In his afterword, looking back on the collection he declares himself very happy with what he said and what he singled out.

'Here I am, fifty years later, rereading my columns, and I am very happy to tell you, dear reader, that I find that what I wrote is still very good. I am almost amazed how good I was and, also, how right I was.' He has no feeling, however, that his work is done. 'The arts of the moving images are again undergoing an intense transformation ... They are as in much in need of a midwife and a passionate defender as they were fifty years ago when technologies, content, and forms were experiencing similar change.' Movie Journal is an invigorating blast, and reading it could well inspire writers to take up Mekas's challenge.

Comments powered by CComment