- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

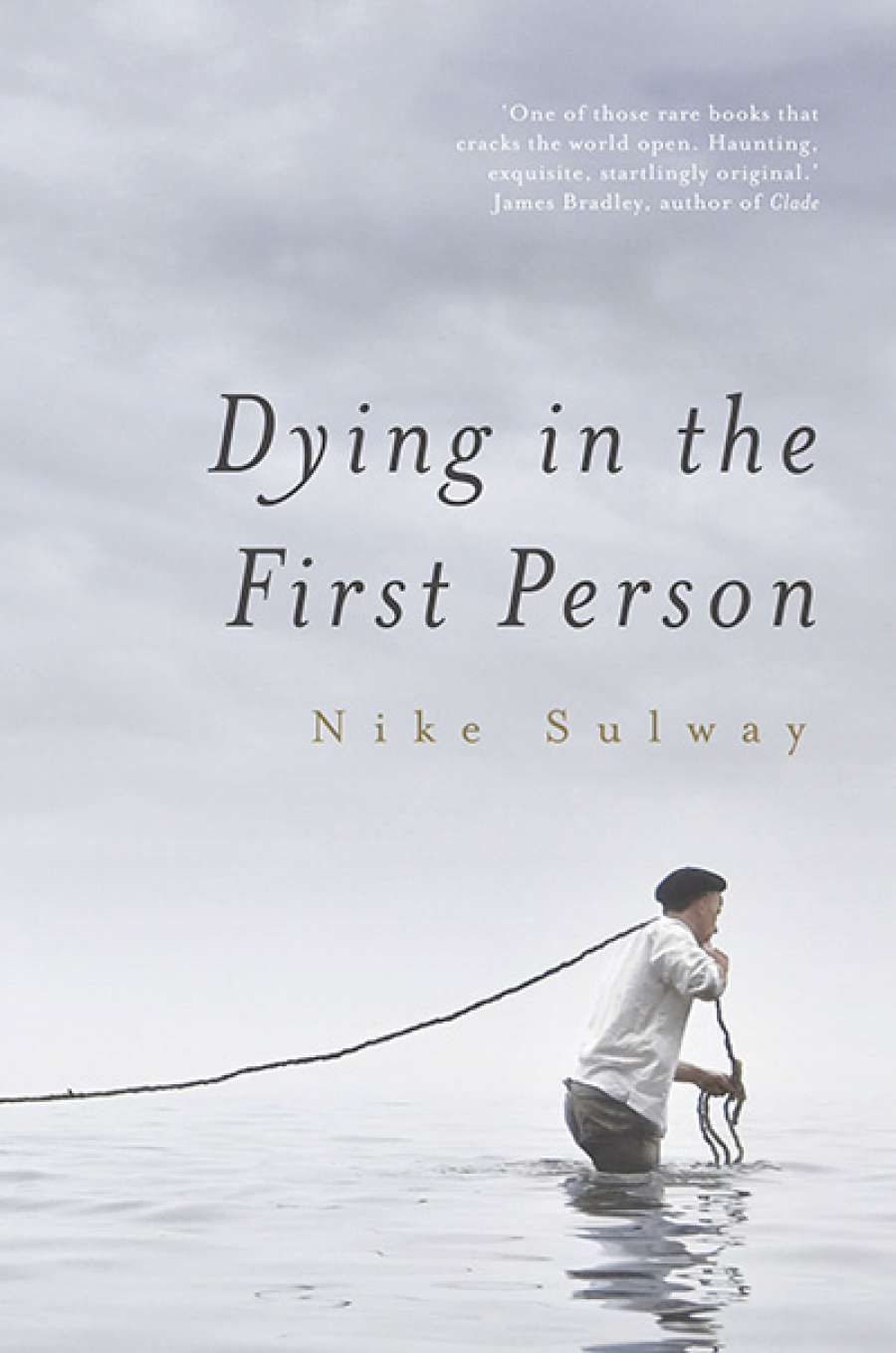

- Custom Article Title: Shannon Burns reviews 'Dying in the First Person' by Nike Sulway

- Custom Highlight Text:

During boyhood, Samuel and his twin brother, Morgan, invent and in a sense inhabit a world and language called 'Nahum'. Years later – after a family tragedy ...

- Book 1 Title: Dying in the First Person

- Book 1 Biblio: Transit Lounge $29.95 pb, 304 pp, 9780994395832

The first paragraph offers a taste of things to come: the word 'body' appears four times, a reiterative strategy that Sulway employs too often, so that poetic intensity gives way to dullness. There are 'mooching' dogs nearby, a sensuous, jaunty description which seems to contradict the mournful mood. The second paragraph aligns Morgan's death with his father's, and thereby hints that the novel will explore the consequences of both deaths – as it does. Indeed, Sulway makes use of foreshadowing to gothic proportions, and that genre looms large throughout.

Dying in the First Person is, above all, a novel of metaphors. At times they are deployed reiteratively, as another way of expressing a thought or feeling, to the point of over-explaining; at other times they extend or exaggerate beyond the original meaning, to the point of confusion.

For Nietzsche, language and the concepts we use to understand the world are inherently metaphorical, yet we forget their true function and confuse the metaphor with reality. Sulway's use of metaphor apes this process, particularly those metaphors that deal with translation, which she symbolically links with death. For example, when Samuel takes his translation work outdoors, he begins with a metaphor: 'The sentences rose up between my feet, took on the shape of trees and hills and paths ... the curvature of the earth a chapter, this stretch of land a paragraph ...' Another metaphor follows: 'I wrote from a kind of madness born of occluded vision.' Then he mixes the metaphors: 'I felt my way in the dark, pushing my roots into the soil.' The perspective shifts here and Samuel goes from producing tree-words to being tree-words, with his (metaphorical) roots pushing down to the earth's core. Then the actual Samuel makes the metaphor literal, removing his boots and socks to press his feet into the earth: 'I walked, barefoot, until the earth came into my body ... I learned the earth by accommodating my body to its lines. Just as I had to open myself to my brother's work, walk its lines until it entered me.' We learn that, for Samuel, trees are (metaphorical) translators of the earth. Finally, Samuel presses his bare feet, bare hands, and bare heart against the pages of his brother's fiction, as an act of (metaphorical) translation.

Whether or not the bare feet and hands are as metaphorical as Samuel's bare heart is impossible to tell by this point, but one thing is clear: like everyone who takes metaphors too literally, Samuel is something of an idiot. Sulway employs a fundamentally comedic conceit – a character's failure to distinguish between figurative and literal language and thought – in deep earnest.

Nike SulwaySamuel writes approvingly of Morgan's 'use of metaphor to awaken the reader, to make them, at last, responsible for the words they hold in their hands' and 'to make the latent actual, to puncture the reader's lassitude'. The assumption behind this strategy seems to be that readers are not as active or attentive as they should be, and require metaphor-prods to keep them alert.

Nike SulwaySamuel writes approvingly of Morgan's 'use of metaphor to awaken the reader, to make them, at last, responsible for the words they hold in their hands' and 'to make the latent actual, to puncture the reader's lassitude'. The assumption behind this strategy seems to be that readers are not as active or attentive as they should be, and require metaphor-prods to keep them alert.

The novel's symbolism is equally heavy-handed. After learning that Ana kept a pet crow as a girl, Samuel confides: 'The wings of the black crow spread and cracked beneath my chest, pausing to glide.' Ana is often found near or in water, and she likes to open the car window so she can feel the rain on her face and hair. Indeed, the rain proves to be a great stimulus for a prospective romance – and the clichés gather apace.

Sulway's method of characterisation embraces caricature. Her protagonists are elaborately cultured and artsy, interested in fine food, rare books, and rustic living. The twins' mother, Solange, is a sharp-minded, French-speaking librarian-cum-bookshop owner who knows Latin and can discuss Housman's poetry and 'the critical edition of Manilius's Astronomica' at careful length while receiving medical treatment. Their father, Paul, holds forth on diverse subjects like 'economics, astronomy, natural philosophy, etiology, chance', and celebrates the anapaestic tetrameters of Dr Seuss. Paul 'circumnavigated the globe when he was seventeen, and perhaps the heavens'; he recites Homer while urinating and sings Norse hunting songs while fishing. Paul's flaws are equally inflated, while his job as a fisherman is purely symbolic. In fact, all labour (especially translation) is pointedly symbolic in Sulway's hands.

Coupled with this, the novel's style is so fixed that Sulway cannot shift between points of view in a credible way. Everything is written in a lyrical mode, employing sensuous descriptions and untethered metaphors. Despite the two narrators' vastly different personal histories, their voices are distinguishable only by a shift in pacing.

Ultimately, the world of Nahum holds more promise than the world of Sulway's novel. She is a fine stylist, but the better qualities of Dying in the First Person – its resonant imagery and elegant phrasing – are undermined by an excessive devotion to metaphor and melodrama.

Comments powered by CComment