- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

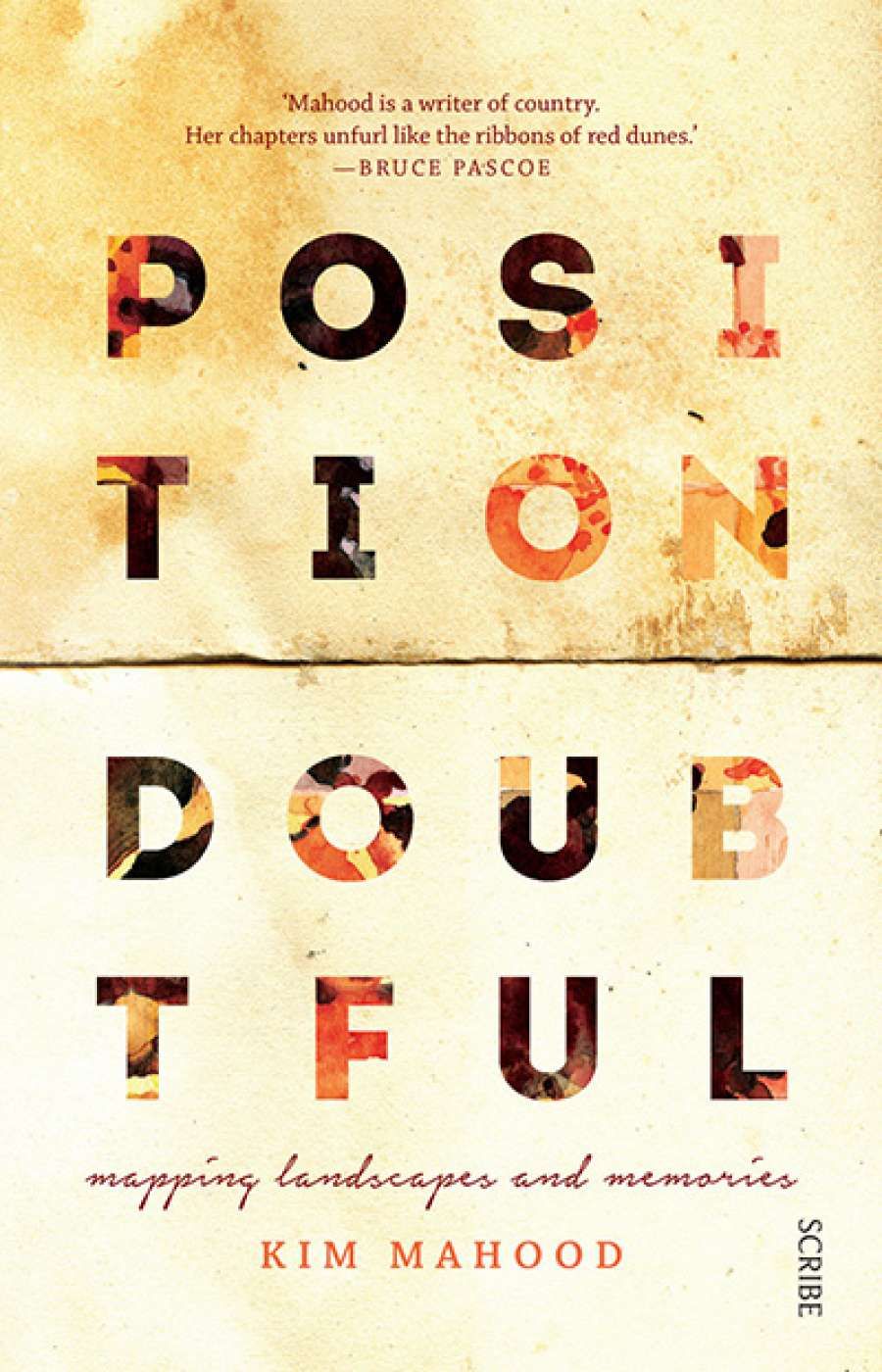

- Custom Article Title: Michael Winkler reviews 'Position Doubtful: Mapping landscapes and memories' by Kim Mahood

- Custom Highlight Text:

At the bottom of one of Kim Mahood's desert watercolours, she scrawled, 'In the gap between two ways of seeing, the risk is that you see nothing clearly.' A risk for ...

- Book 1 Title: Position Doubtful

- Book 1 Subtitle: Mapping landscapes and memories

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe $29.99 pb, 336 pp, 9781925321685

As a child, Mahood lived on Mongrel Downs station in the Tanami Desert. She returns to the region annually, sketching, painting, and photographing the landscape, camping beside lakes and dry creek beds, and working in small communities including Balgo and Mulan. The binocular vision that comes with her status as both insider and outsider allows for hard-won insights into desert painting and remote community life, 'both vertigo-inducing in their different ways'.

Mahood interleaves what she observes into ongoing musings about geography, community development, and relationships between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians. This is terrain – physical and psychic – which she traversed in her award-winning memoir Craft for a Dry Lake (2000). Mahood becomes fascinated by mapping, overlaying Western cartography with Aboriginal stories and art. The book's (perfect) title is from a locution of her father's in his 1962 account of exploring the Tanami Stock Route. She ponders ancient waterways beneath the desert sands, and posits that these venerable formations shape the contemporary land, just as the Dreamtime is coevally present and past for people in those communities. Attracted to the practical rather than the theoretical, she enacts this layering of knowledge through several large communal mapping exercises that are realised as works of art.

By contrast, Mahood's collaborator, camping companion, friend, and foil Pamela Lofts arrives at her artistic standpoint through the portal of post-colonial and feminist critique. Mahood considers them fashionable but blunt instruments unsuitable for understanding the endlessly varied picture of indigenous Australia. 'That I was out of step with the intellectual and academic temper of my time troubled me, but I could not submit to the reductionism,' she writes.

The book is in part an elegy for Lofts. The Alice Springs-based painter and photographer used the word 'dystopothesia' to describe 'what she felt to be a fundamental condition of displacement for both black and white Australians', but is presented as a more sanguine, sunny character than the author. Lofts's death is one of many. Mahood etches her grief at the 'cascading losses' without extravagance; rather, the precision is powerful: 'she had the last word so definitively that I am left with a hum of unspoken responses, distracting and incoherent as tinnitus'.

The Tanami Track (photograph by Robert E. Welsh, Wikimedia Commons)

The Tanami Track (photograph by Robert E. Welsh, Wikimedia Commons)

In Finding Eliza: Power and colonial storytelling (2016), Larissa Behrendt decried the falseness of many white representations of indigenous Australians. '[A]ny confrontational aspect of the Aboriginal presence is stripped away in portrayal of the passive Indigenous person', while 'perceived mystical characteristics or idealised traits' are invented or emphasised. Mahood, tough as emu jerky, never errs in this regard, because she has the courage not to pander – either to the Aboriginal people she knows, or to the largely non-indigenous readership that will approach her book with predictable preconceptions.

There are two campfires of historical opinion that have burned with more heat than light over recent decades. People beside the first fire believe their adversaries are racist. Those at the second fire sneer that people in the other group wear a black arm-band. Mahood eschews the comfort of either camp. She sees what she sees, and comes to her own conclusions.

In one fascinating chapter she travels with senior community members to what they claim was the site of a massacre. Mahood tests their stories and points out holes in the narrative, but her conclusion provides no comfort to either side of the political divide. She decides that the story as told cannot be true, but that it has a factual basis. The oral testimony 'throws a long shadow across the well-lit pioneer myths', even though it could not withstand forensic examination.

Kim MahoodMahood wears 'a skin both absorbent of cross-cultural nuance and resistant to manipulation' and resists the push-pull attempts of those on either side of the racial gulch. Perhaps it is this stubborn-mindedness that impels her to use the needlessly provocative term 'white slave' (which also appears in at least two other pieces she has written). Her valid point about the contortions some non-indigenous people perform in order to expiate guilt or avoid giving offence is well made without this overreach.

Kim MahoodMahood wears 'a skin both absorbent of cross-cultural nuance and resistant to manipulation' and resists the push-pull attempts of those on either side of the racial gulch. Perhaps it is this stubborn-mindedness that impels her to use the needlessly provocative term 'white slave' (which also appears in at least two other pieces she has written). Her valid point about the contortions some non-indigenous people perform in order to expiate guilt or avoid giving offence is well made without this overreach.

Mahood is simultaneously in the middle and a permanent outsider. So it is that, while she remains fixed on questions of landscape and geography, the reader becomes increasingly intrigued by her. She appears able to slip through the seemingly impermeable membrane between black and white Australia when she chooses to, but pleads that, 'It is often assumed that I know much more than I do, and understand more.' Mahood's ultimate destination is a state where land and story are unified, where 'The boundaries of people's knowledge are fluid, morphing and overlapping.' The palimpsest that is marked and ablated and marked again is country and history, individual and collective, layered and fused.

Thirty-six photographs, paintings, and maps are included, but the grey-scale reproductions are frustratingly small. A book of this quality, drawn from the spectacular realms of desert landscape and visual art, deserves colour plates.

Comments powered by CComment