- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

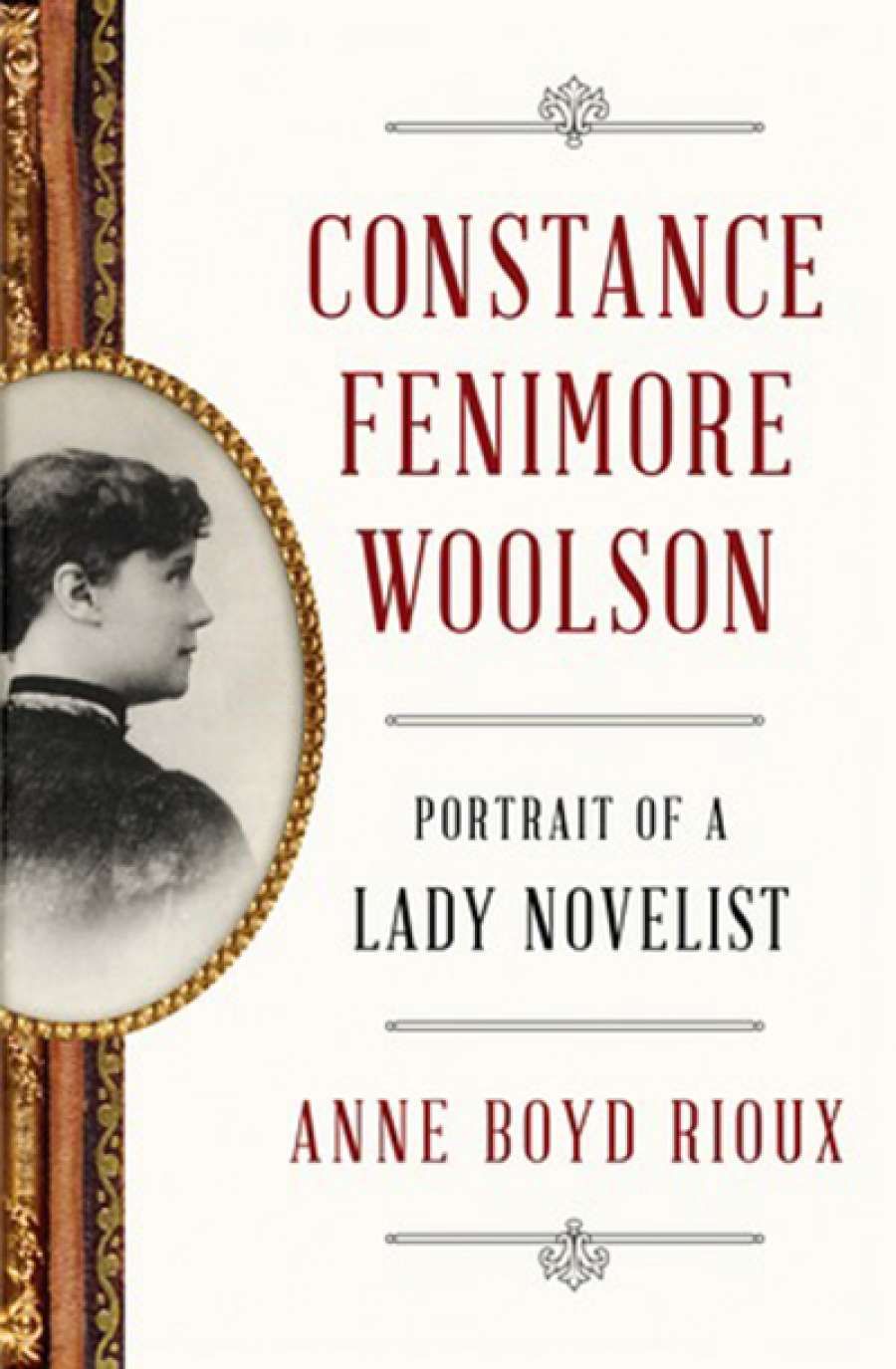

- Custom Article Title: Brenda Niall reviews 'Constance Fenimore Woolson: Portrait of a lady novelist' by Anne Boyd Rioux

- Custom Highlight Text:

If Constance Fenimore Woolson is remembered today, it is likely to be as a friend of Henry James, and a minor character in his much-chronicled life. Anne Boyd Rioux's ...

- Book 1 Title: Constance Fenimore Woolson

- Book 1 Subtitle: Portrait of a lady novelist

- Book 1 Biblio: W.W. Norton & Company Inc. (Wiley) $46.95 hb, 416 pp, 9780393245097

The subtitle, Portrait of a lady novelist, invokes James's Portrait of a Lady (1881). Rioux sees Woolson as a version of Isabel Archer, as ardent and independent as Isabel was, but gifted with a creativity that Isabel did not possess. Woolson was 'a woman as beguiling as any of James's heroines'. That's quite a stretch from James's own words. Woolson, he said, was 'old-maidish, deaf & intense but a good little woman & a perfect lady'. She was also intelligent, witty, and undemanding. James came to rely on her friendship during sojourns in Florence and Venice.

The expatriates first met in Florence in 1880, when she was forty years old and James was thirty-seven. After the death of her father, an Ohio businessman, Constance had earned a moderate living as a newspaper columnist, novelist, and short story writer. Her biographer gives a well-researched account of her family and career. Woolson was a great-niece of James Fenimore Cooper, author of The Last of the Mohicans (1826). Her immediate family background was one of loss, marked by the early deaths of five of her six sisters, and by her father's financial failures. Born in New Hampshire, she grew up in Ohio and went to finishing school in New York. Her move to Italy, where she could live more cheaply than in the United States, was a way to enrich her fiction, pay the bills, and satisfy her love of art.

The subtitle also recalls George Eliot's 1856 demolition piece, 'Silly Novels by Lady Novelists', in which Eliot gave exasperated attention to the 'frothy, prosy, pious and pedantic' writers who were enjoying good sales. Woolson, as Anne Boyd Rioux shows, was better than that. Yet, unlike the work of her contemporaries and fellow Americans, Kate Chopin and Sarah Orne Jewett, Woolson's novels and stories have never had a revival.

I am sceptical about the suggestion that Woolson's obscurity is Henry James's fault. 'Her life story has never been fully or adequately told in large part because it has been eclipsed by James's', the biographer believes. It is more plausible that the extraordinary attention accorded to James's life and work has created Woolson; she can be made to fill an emotional gap in his narrative.

For a time, Edith Wharton was best known as a friend of the Master, and for some critics her work was simply lightweight James. Yet, as soon as her novels came back into print in the 1960s, her distinctive talent was recognised. To be a friend of James wasn't necessarily fatal for an aspiring woman writer. Wharton was never James's victim, nor was she overly-impressed by his late fiction. 'I broke a tooth on The Golden Bowl,' she remarked.

The contrasting fortunes of James and Woolson illuminate late-nineteenth-century literary taste; for a time her work sold far better than his. She has been seen as the original of May Bartram, the devoted woman who watches over the self-absorbed John Marcher in 'The Beast in the Jungle'. Rioux spells it out, claiming that Woolson's death taught James that 'to love deeply was the great thing, the only thing perhaps'. Her death in 1894, a presumed suicide, by jumping or falling from a high window in her Venetian apartment, prompted James to blame himself for having been a neglectful friend. More than a friend, Rioux believes; there was 'a bond of mind and heart'. This seems an idealised reading: neither James nor Woolson left records to show such a bond.

Colm Tóibín's The Master (2004) has some splendidly eerie imagined scenes in which James destroys evidence of his friendship with Woolson. After her death, he burns letters and other papers in her apartment; he then loads a gondola with bundles of clothing which he attempts to submerge in the canal. Her bulky dresses refuse to drown, as does her troubling memory.

Portrait of Constance Fenimore Woolson (1840–94) in Queries magazine, October 1886 (Harper Brothers)Rioux doesn't make much of this story. She does, however, find a secret intimacy in the six weeks they spent, in separate apartments, in the same building in Florence. This is represented as a daring breach of convention. But, given that Constance received a 'constant stream of visitors', it doesn't seem that she was unduly worried about her reputation.

Portrait of Constance Fenimore Woolson (1840–94) in Queries magazine, October 1886 (Harper Brothers)Rioux doesn't make much of this story. She does, however, find a secret intimacy in the six weeks they spent, in separate apartments, in the same building in Florence. This is represented as a daring breach of convention. But, given that Constance received a 'constant stream of visitors', it doesn't seem that she was unduly worried about her reputation.

Outside his family, Rioux believes, Constance came first in Henry's affections. Given his self-protective discretion and the presumed destruction of letters between them, it can't be known that the two of them were as close as Rioux suggests. Her summary suggests a mutual decision: 'they would not marry; they would not live in the same apartment; they would not have a physical relationship.'

But were they so close? James appears not to have known her financial difficulties, nor that she suffered from depression. He was patronising about her novels; she criticised him for his inability to develop a plot and for never showing his characters in love. As a story of a warm but at times abrasive friendship, and as a study of a professional woman writer whose work never quite satisfied her ambition, Constance Fenimore Woolson has much to offer. But despite its author's best intentions, it is dominated by Henry James.

Comments powered by CComment