- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

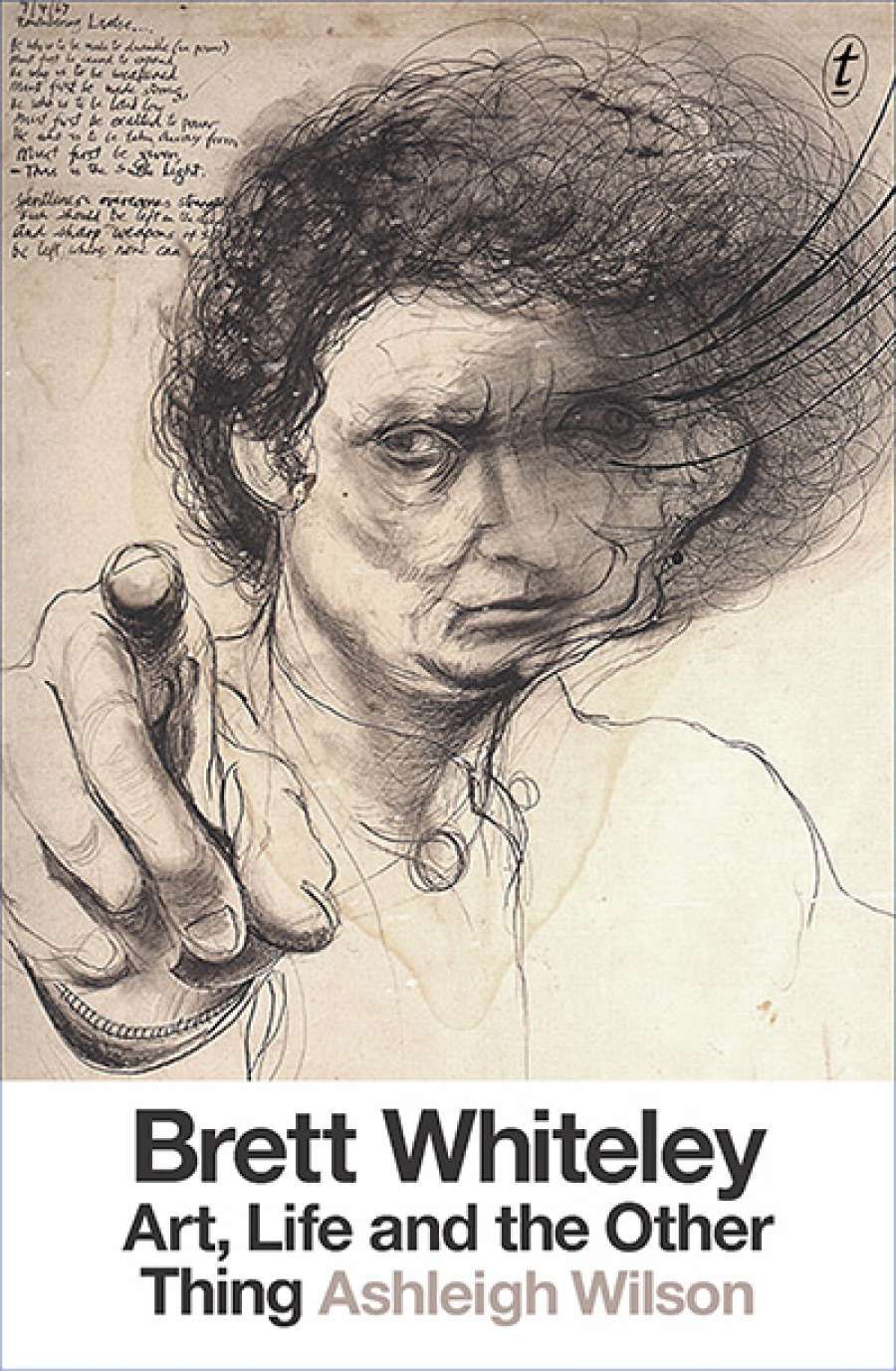

- Custom Article Title: Simon Caterson reviews 'Brett Whiteley: Art, life and the other thing' by Ashleigh Wilson

- Custom Highlight Text:

Notwithstanding the fact that he died alone in a hotel room following a heroin overdose at the age of fifty-three, Brett Whiteley led what for an Australian artist ...

- Book 1 Title: Brett Whiteley

- Book 1 Subtitle: Art, life and the other thing

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $49.99 hb, 464 pp, 9781925355239

Encouraged by the likes of Lloyd Rees, Francis Bacon, Sidney Nolan, and Kenneth Clark, Whiteley flourished in London. That halcyon period of cultural expatriatism peaked in the 1960s and lasted until the UK government decided to make it harder for Australian and other Commonwealth passport-holders to stay in Britain. Moving from London to New York on a Harkness Fellowship, Whiteley lived at the Hotel Chelsea, encountering the likes of Leonard Cohen, Janis Joplin, and Jimi Hendrix. His presence in the American art scene, however, did not have the same impact as it had in the United Kingdom. Whiteley nevertheless produced the multi-panel, mixed media work entitled The American Dream (1968–69), which served as a major calling card when he eventually returned to Australia in 1969.

Despite the New York disappointment, Whiteley had been provided with as effective an international launching pad as any Australian painter of his era could have wished for. He early achieved a prominence that fortified his reputation against negative criticism as he developed as an artist. Starting in his early twenties, what Brett Whiteley did was news and his technical accomplishments commanded a certain respect. 'Even critics who disliked Brett's themes acknowledged his skills as a draughtsman,' notes Wilson.

In addition to all that talent, precocious luck, and institutional support, the most significant boon in Whiteley's story was his good fortune in meeting and marrying Wendy Julius. Her remarkable patience and forbearance, as much as the inspiration she provided as long-legged muse, helped advance and sustain his career, and later protect his legacy. Whiteley cheated on Wendy – and she had affairs that caused him torment – but he also appreciated how much he depended on Wendy; he once described her as 'an inexorable part of my creative process'. Wendy in turn believed in him, and the lasting value of that support cannot be underestimated for all the public swagger he displayed and the affairs he pursued. The two of them certainly used a lot of heroin as a couple, 'bound together in a shared dependence', as Wilson puts it. 'It helped that Brett, when stoned, was less likely to chase other women.' Eventually, they divorced when Wendy broke the heroin habit and he could not.

Although Whiteley did important early work in London, New York, and Fiji, he is most closely identified with Sydney, the city that bears the indelible mark of his imagination in those famous bottomless views of the Harbour and the bottom-filled paintings of female bathers on Bondi Beach. Always a full-blooded eroticist, Whiteley captured the humid sensuousness of Sydney as stirringly as any artist before or since.

Whiteley's studio – a converted T-shirt factory tucked away down a back lane in Surry Hills – is now a public art museum bought by the New South Wales state government with the support of Wendy; it is preserved as if the artist is still working there. Perhaps no other Australian artist – certainly none as closely associated with Sydney – has such a fine permanent public memorial.

Brett and Wendy Whiteley married at the Chelsea Registry office, 1962 (Courtesy of the Brett Whiteley estate)Wilson analyses Whiteley's contradictions with precision. The duality of man – a fashionable concept in the 1960s – is a constant theme in Whiteley's early work. In his own personality, Brett Whiteley was a mixture of the wild and the disciplined, the extravagant and the self-contained. A painter friend of mine said recently that she thought every artist has a touch of OCD, and Whiteley certainly was obsessive about making art.

Brett and Wendy Whiteley married at the Chelsea Registry office, 1962 (Courtesy of the Brett Whiteley estate)Wilson analyses Whiteley's contradictions with precision. The duality of man – a fashionable concept in the 1960s – is a constant theme in Whiteley's early work. In his own personality, Brett Whiteley was a mixture of the wild and the disciplined, the extravagant and the self-contained. A painter friend of mine said recently that she thought every artist has a touch of OCD, and Whiteley certainly was obsessive about making art.

Whiteley could also perhaps have been diagnosed with ADD. His mind tended to wander while he spoke in interviews, and he kept trying new forms and subject matter. Some of his most striking sculptures are made out of trash: an owl is made from a boot, ping-pong balls, and steel hooks. Whiteley was one of those rare and special artists who not only seemed willing to try anything in any genre or medium, but was quite capable of pulling it off. 'You are only limited by your talent,' he wrote in a notebook, 'and talent is often simply courage.'

As a committed artist, Whiteley was pulled along by his senses and an undimmable natural curiosity. He was open to all kinds of Western and non-Western influences, borrowed freely from history and popular culture, travelled extensively, and experimented with different drugs in order to extend his creative reach. He believed that making art was a portal to a higher consciousness, and he lived in an era when this notion was taken seriously by many people. He followed current affairs, though some of his views – concerning, say, the benefits of Chinese communism – seem naïve.

Beyond the fascination of the biographical subject and the extraordinary range of his work, a major pleasure to be discovered in reading Ashleigh Wilson's book is that the author does not seek to interpose himself between the reader and Brett Whiteley.

Brett Whiteley's studio in Surry Hills, NSW (photograph by Dylan Coleman, via Flickr)

Brett Whiteley's studio in Surry Hills, NSW (photograph by Dylan Coleman, via Flickr)

Wilson concentrates on marshalling the relevant facts into a smoothly flowing narrative and does the reader the courtesy of allowing us to form our own judgements. Perhaps it is just as well for a biographer not to get caught up in unnecessary exegesis. As Whiteley once remarked contemptuously of those who took a negative view of his work: 'Critics are the dildoes [sic] of art'.

For those readers who delight in much of Whiteley's best work, this book is essential reading. It illuminates the awe-inspiring creative force beyond the only-in-Sydney celebrity image of the cheeky Harpo Marx-haired short-arsed sex pixie who wore Mao suits with bucket hats and partied with famous rock stars while carrying around big rolls of cash in his flash convertible. He was doing so well financially in Australia in the last decade or so of his life that he didn't bother exhibiting overseas.

Neither hagiography nor hatchet job, Brett Whiteley: Art, life and the other thing is a clear-eyed account of an artist whose output was vast, if uneven, and whose legacy looms large in the history of modern art. Ashleigh Wilson provides an object lesson in writing the life of an artist.

Comments powered by CComment