- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

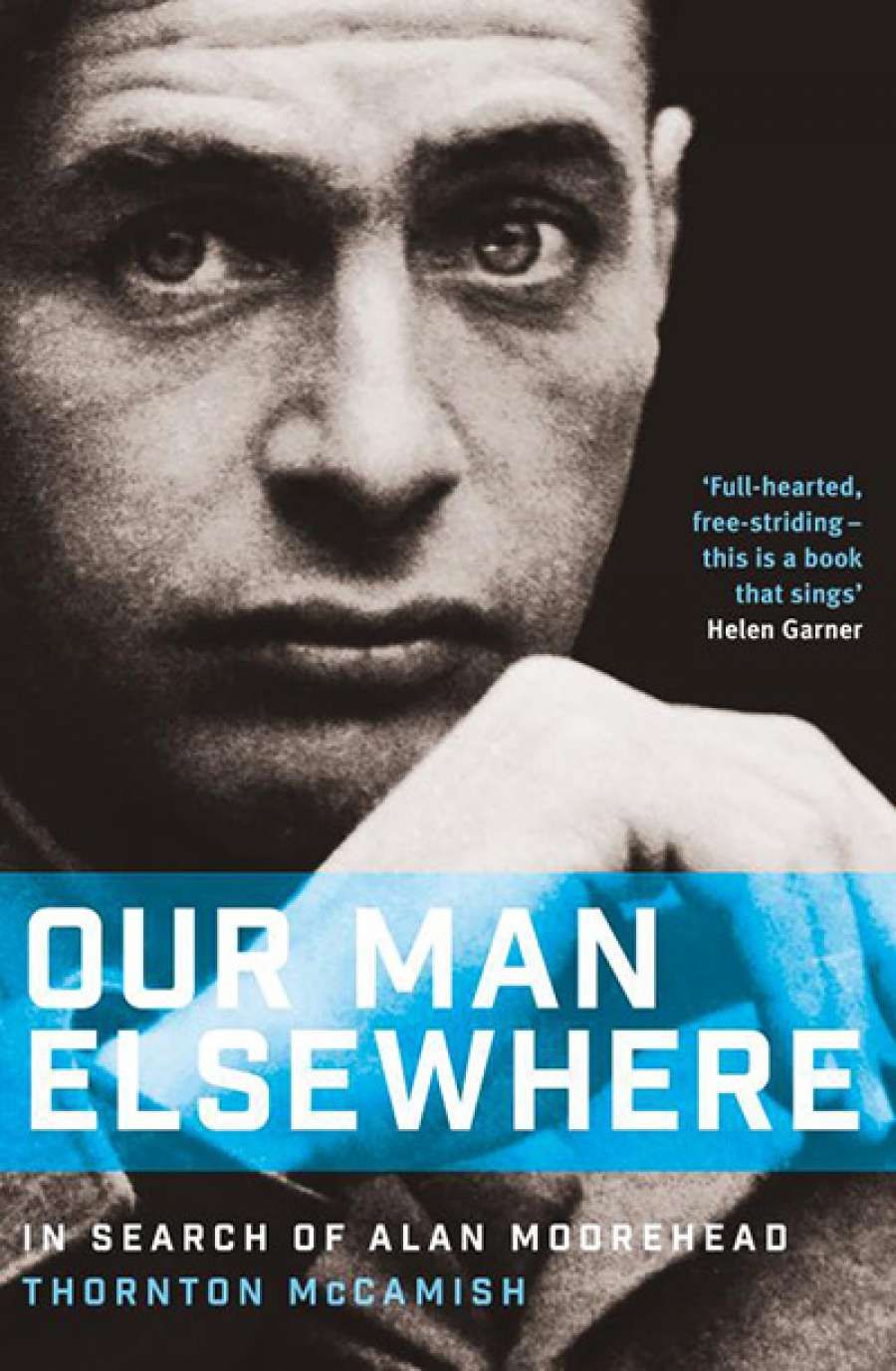

- Custom Article Title: Robin Gerster reviews 'Our Man Elsewhere: In search of Alan Moorehead' by Thornton McCamish

- Custom Highlight Text:

You have to admire the professional writer who describes the chore of churning out the daily ration of words as 'like straining shit through a sock', ...

- Book 1 Title: Our Man Elsewhere

- Book 1 Subtitle: In search of Alan Moorehead

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $39.99 hb, 324 pp, 9781863958271

Moorehead left his reporter's job at the Melbourne Herald in 1936 and headed for London, a familiar antipodean rite de passage, where he found work with Beaverbrook's Daily Express. He was soon appointed to the paper's Paris bureau and was running its Rome office when Germany invaded Poland. As an accredited war correspondent in North Africa and Europe, he saw and covered more of the conflict than just about anyone, and produced the quartet of books – the African Trilogy (1945) and Eclipse (1946) – that made his fame. Before the war, he witnessed France's last public execution by guillotine, and in early 1938 he met and drank whisky with his hero Ernest Hemingway in Spain. After the war, he courted and befriended the rich and famous. He had his photograph taken with Winston Churchill. Clearly, he had made the right career move.

But do people still read Alan Moorehead? A few of his books are occasionally reissued, but his reputation, as McCamish wryly notes, falls into the category of 'remaindered Australiana' (unfair given the vast transnational scope of his work). He is unfashionable, perhaps terminally so. The index to The Cambridge History of Australian Literature (2009) reveals just one reference, and that is to his war reportage. He was a big name in my youth, in the 1960s. I remember being transfixed by his story of the Burke and Wills misadventure, Cooper's Creek (1963), with each agonising page pushing the hapless protagonists closer to their doom. I returned to Moorehead recently, reading his travel book of Australia's north Rum Jungle (1953), which revealed some unappealing if not atypical attitudes. The uranium pioneering of the early 1950s was easily integrated into the master narrative of the conquest of an alien continent, giving meaning to an Aboriginal landscape that was beyond civilisation's pale. 'Absolutely nothing' had happened in the Australian desert, he wrote, 'except the roamings of the aborigines and the kangaroos and the interminable munchings of the white ants': an interesting grouping of native fauna.

Journalists Alan Moorehead (left) and Alexander Clifford (right) in the North African desert in 1942 (Wikimedia Commons)

Journalists Alan Moorehead (left) and Alexander Clifford (right) in the North African desert in 1942 (Wikimedia Commons)

Yet Moorehead's account of the damage to the indigenous peoples of the Pacific wrought by colonialism, The Fatal Impact (1966), revealed a sensibility capable of transcending its time. Robert Hughes borrowed half the title for his masterpiece The Fatal Shore (1986), a work he dedicated to Moorehead and his British wife Lucy. Moorehead's Gallipoli (1956) is an early and signally important contribution to what has since become the Anzac industry. The worldliness and sinewy prose of his Australian books provide a bracing antidote to the windy portentousness and narrow nationalism of contemporary Australian popular history, as notably practised by Peter FitzSimons. As both a significant individual figure and a writerly exemplar of his time and place, Moorehead warrants the kind of sympathetic investigation that McCamish provides in Our Man Elsewhere.

This is no mere objective biography. McCamish uses 'the time-machine' of Moorehead's prose as a vehicle to re-enter the 'lost world' (a trope used frequently in the book) of a generation of writer-travellers made obsolete by the postmodern curse of globalisation. Moorehead's appeal, as McCamish frankly admits, is driven by nostalgia. While he is at pains to keep some kind of critical distance from his subject, McCamish admits to a 'fantasy identification' with Moorehead himself, as one who had fled his own home town to record a world by turns glamorous and tragic.

Harbour view from the 'rocca', Porto Ercole (Wikimedia Commons)McCamish is there every vicarious step of the way, both physically and imaginatively visiting the places his subject lived and worked. In Cairo he checks into the Hotel Carlton (the colonial relic where Moorehead stayed as a young war correspondent) in order to 'tune in to Moorehead frequency across time', trying to 'channel the spirit' of his 'quarry'. He hunts down the writer's various Italian haunts, travelling to Taomina in Sicily, to Fiesole and to Porto Ercole, where The Blue Nile (1962), Cooper's Creek, and The Fatal Impact were written. And he rummages through the Moorehead papers in the National Library of Australia. Channelling him from a room in a depressing motel in Queanbeyan on a final research trip to Canberra – 'maybe not so different from Moorehead's basic hotel room in Valencia in 1937' – is perhaps one imaginative leap too many.

Harbour view from the 'rocca', Porto Ercole (Wikimedia Commons)McCamish is there every vicarious step of the way, both physically and imaginatively visiting the places his subject lived and worked. In Cairo he checks into the Hotel Carlton (the colonial relic where Moorehead stayed as a young war correspondent) in order to 'tune in to Moorehead frequency across time', trying to 'channel the spirit' of his 'quarry'. He hunts down the writer's various Italian haunts, travelling to Taomina in Sicily, to Fiesole and to Porto Ercole, where The Blue Nile (1962), Cooper's Creek, and The Fatal Impact were written. And he rummages through the Moorehead papers in the National Library of Australia. Channelling him from a room in a depressing motel in Queanbeyan on a final research trip to Canberra – 'maybe not so different from Moorehead's basic hotel room in Valencia in 1937' – is perhaps one imaginative leap too many.

It is a dangerous business, placing oneself in a biography. McCamish pulls it off, mostly, though tracking down 'Casa Moorehead' at Porto Ercole takes several overwrought pages. There are moments when McCamish's own travel writing takes off. Breakfasting on 'a boiled egg and a toothsome croissant the size of a hat' at the Hotel Carlton, he is served by an ancient waiter in fez and waistcoat, who 'moved with an exquisite lack of haste, and managed to radiate such a long-suffering contempt for both me and his tasks that his carriage of the tea tray from kitchen to table was a kind of performed critique of the colonial legacy'.

Whether the close identification with his subject makes Moorehead 'reappear', as McCamish hopes, is doubtful. As the work's intriguingly oblique conclusion implies, Moorehead remains an elusive, contradictory figure – the 'man elsewhere' in every sense of the term. Moorehead lived for another seventeen years after suffering a catastrophic stroke in 1966; he died in London. He survived the car crash that killed his wife, but after the stroke he never wrote again. Instead he took up painting, inspired by Aboriginal rock art. McCamish notes that he would go to the zoo in Regent's Park, to paint the animals. At the end of his life, the writer once gratefully liberated from the constrictions of provincial Australia took to painting kangaroos at the London Zoo.

Comments powered by CComment