- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

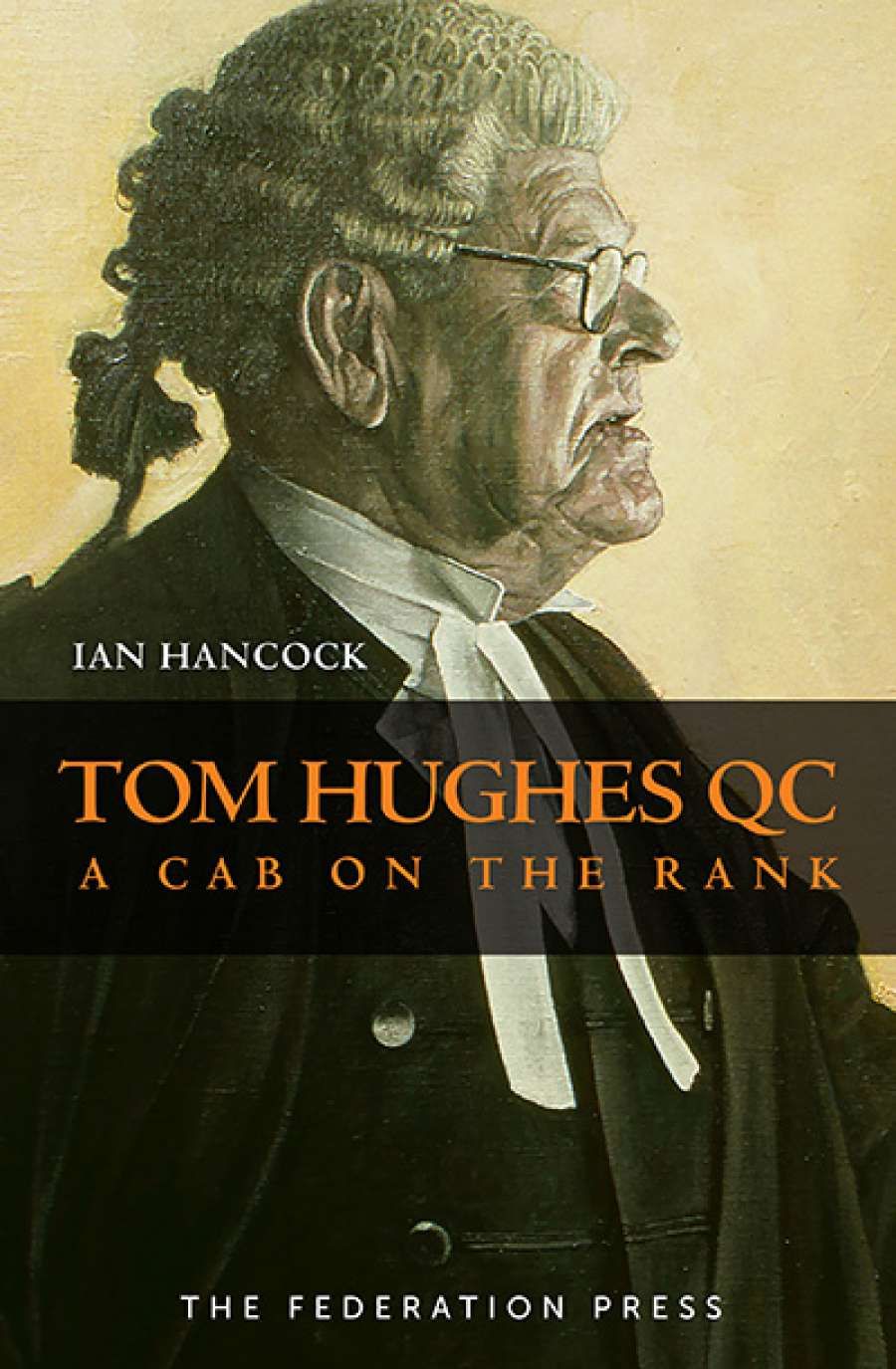

- Custom Article Title: Peter Heerey reviews 'Tom Hughes QC: A cab on the rank' by Ian Hancock

- Custom Highlight Text:

The subtitle of this compellingly readable biography of Thomas Eyre Forrest Hughes AO QC borrows the underlying philosophical metaphor of the independent Bar ...

- Book 1 Title: Tom Hughes QC

- Book 1 Subtitle: A cab on the rank

- Book 1 Biblio: Federation Press, $59.95 hb, 414 pp, 9781760020583

An argument which does not convince yourself, may convince the Judge to whom you urge it; and if it does convince him, why Sir, you are wrong, and he is right. It his business to judge; and you are not to be confident in your own opinion that a cause is bad, but to say all you can for your client, and then hear the Judge's opinion.

Through a career at the Sydney Bar from 1949 to 2012, Tom Hughes plied his trade as a barrister for clients famous and infamous, in cases celebrated and routine, but always with superb advocacy skills backed by meticulous preparation.

If it were no more than a catalogue of cases, however famous, such an account might lack insight into the character of the advocate whose story is being told. But the author, a distinguished historian, has had the advantage of frank interviews with many of Hughes's contemporaries. Also there are some valuable documentary sources. Ordinarily, barristers do not keep much in the way of records. Indeed, one of the attractions of the profession is that once the case is over the papers can be handed back. But Hughes was a diligent diarist and keeper of personal papers.

It is a very Sydney story. Hughes's father, Geoffrey Hughes, was a prominent solicitor. His grandfather, Sir Thomas Hughes, was a lord mayor of Sydney. (His daughter Lucy was later to achieve that honour.) His great-great-grandfather, Thomas Hughes, migrated to Sydney from County Leitrim in 1840.

Tom Hughes was educated by the Jesuits at St Ignatius' College, Riverview. He later graduated from the University of Sydney. During World War II, Hughes flew Sunderland flying boats out of England with RAAF 10 Squadron. The Squadron lost 151 men and nineteen aircraft and sank six U-boats. He had, as he modestly puts it, 'a relatively lucky and safe war'.

In 1963, Hughes entered federal politics, winning the seat of Parkes from the sitting Labor member, Les Haylen. While on the back bench, although a conscientious attender at the House he was able to continue his practice at the Bar. In 1964 he achieved a notable victory for the writer Hal Porter who sued the Hobart Mercury in the Supreme Court of Tasmania over a review of The Watcher on the Cast-Iron Balcony (1963), which, as the Court accepted, carried the imputation that Porter had inserted Anglo-Saxon words, not out of literary necessity but to gain publicity by attracting the attention of the censor. Justice Neasey found the preview 'gravely defamatory' and awarded damages of £1,000. Hughes's fee was the then not inconsiderable £435-15-0 plus expenses. (Another valuable resource for the author has been Hughes's fee books, which are cited from time to time to demonstrate how his practice became increasingly lucrative.)

After the 1969 election, Hughes was promoted by Prime Minister John Gorton to Cabinet as attorney-general. This was a time of great controversy over Australia's participation in the Vietnam War. A famous incident occurred when a group of protesters, led by one Ian Macdonald, attempted to invade the Hughes home. (Macdonald was to become a New South Wales Labor minister and still later the subject of adverse findings by ICAC over his dealings with the Obeid family.) Hughes repulsed the would-be trespassers with dextrous use of his son's cricket bat. One of the many comments was that of journalist and Test cricketer of the 1930s, Jack Fingleton: 'Footwork magnificent – cannot be faulted. Grip with bat just a little suspect. Perhaps hands should have been closer together although gap is permissible if stroke is improvised.'

Tom 'cricket bat' Hughes, 16 August 1970 (Bauer Media Limited)When William McMahon replaced Gorton as prime minister in 1972, Hughes was sacked as attorney-general, much to the disappointment of many Liberals. By all accounts, Hughes had successfully balanced the political obligations of a minister with the objectivity required of the attorney-general as first law officer. Clarrie Harders, who had been secretary of the department under eight Attorneys, described him as 'the best Attorney-General under whom I served'.

Tom 'cricket bat' Hughes, 16 August 1970 (Bauer Media Limited)When William McMahon replaced Gorton as prime minister in 1972, Hughes was sacked as attorney-general, much to the disappointment of many Liberals. By all accounts, Hughes had successfully balanced the political obligations of a minister with the objectivity required of the attorney-general as first law officer. Clarrie Harders, who had been secretary of the department under eight Attorneys, described him as 'the best Attorney-General under whom I served'.

One feature of Hughes's attitude to life and career, which the author notes in the particular context of a loss in a difficult case, was that 'just as he was capable of a strong emotional commitment, he was equally adept at moving on'. After a distinguished war record, he nevertheless did not become involved in ex-service activities. After leaving the political scene he did not become an éminence grise in Liberal circles, but confined himself to donations, handing out how-to-vote cards, and writing references for preselection candidates. He moved towards the moderate wing of the Liberal Party, aligning himself with the Australian Republican Movement, led by son-in-law Malcolm Turnbull, and supporting company director Kevin McCann for preselection for the seat of Warringah. (His candidate was defeated by one Tony Abbott.)

Hughes's advocacy style has been described as declamatory and theatrical, a characteristic pose was, with 'menacing pirouette', to address the side, or even the rear of the courtroom. Occasionally there would be penetrating wit, as when he said of a trade union hearing which had expelled his client that to describe it as a kangaroo court 'would be an under-statement and an insult to a great Australian marsupial'.

One celebrated case was Hughes's appearance on behalf of rugby league player Andrew Ettingshausen who sued for defamation when a newspaper published a grainy black-and-white photo showing the plaintiff in the shower with other players after a game. The contention, which the jury ultimately accepted, was that the plaintiff was defamed because readers would think he had consented to the publication of this revealing photograph. Just what the photo revealed was a central issue.

Hughes's cross-examination of the New Zealand-born editor went as follows:

Hughes: It is a penis is it not ...?

Witness: Well, I assume if it's in that part of the body, maybe it could be and maybe it might not be.

Hughes: What else could it be?

Witness: I guess it could be a shadow ...

Hughes: (appropriating the witness's New Zealand accent) Is it a duck?

Witness: I don't think it would be a duck.

Not surprisingly, as the author notes, the growing enthusiasm for mediation in recent years had no appeal for Hughes. However, behind the style lay substance, based on painstaking preparation. He was renowned for regularly catching the 5.30 am bus to his Chambers.

Tom and Chrissie Hughes, February 2016 (Hughes Papers)

Tom and Chrissie Hughes, February 2016 (Hughes Papers)

The story is not confined to the courtroom. The reader learns of the failure of Hughes's first marriage, some relationships, and a long and happy second marriage as well as his abandonment of, and return to, the Catholic faith. As well there is some intriguing gossip about the personalities and internal politics of the Sydney Bar. The actress Kate Fitzpatrick was said to have called Murray Gleeson the sexiest man she had ever met, prompting the comment from Michael McHugh: 'Poor Kate. She must have led a sheltered life.'

Hughes emerges from the book as a warm, generous, and thoughtful man, notwithstanding an initial somewhat austere impression. He had the same secretary for over four decades and the same farm manager for three – a good indication of his human side.

Comments powered by CComment