- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

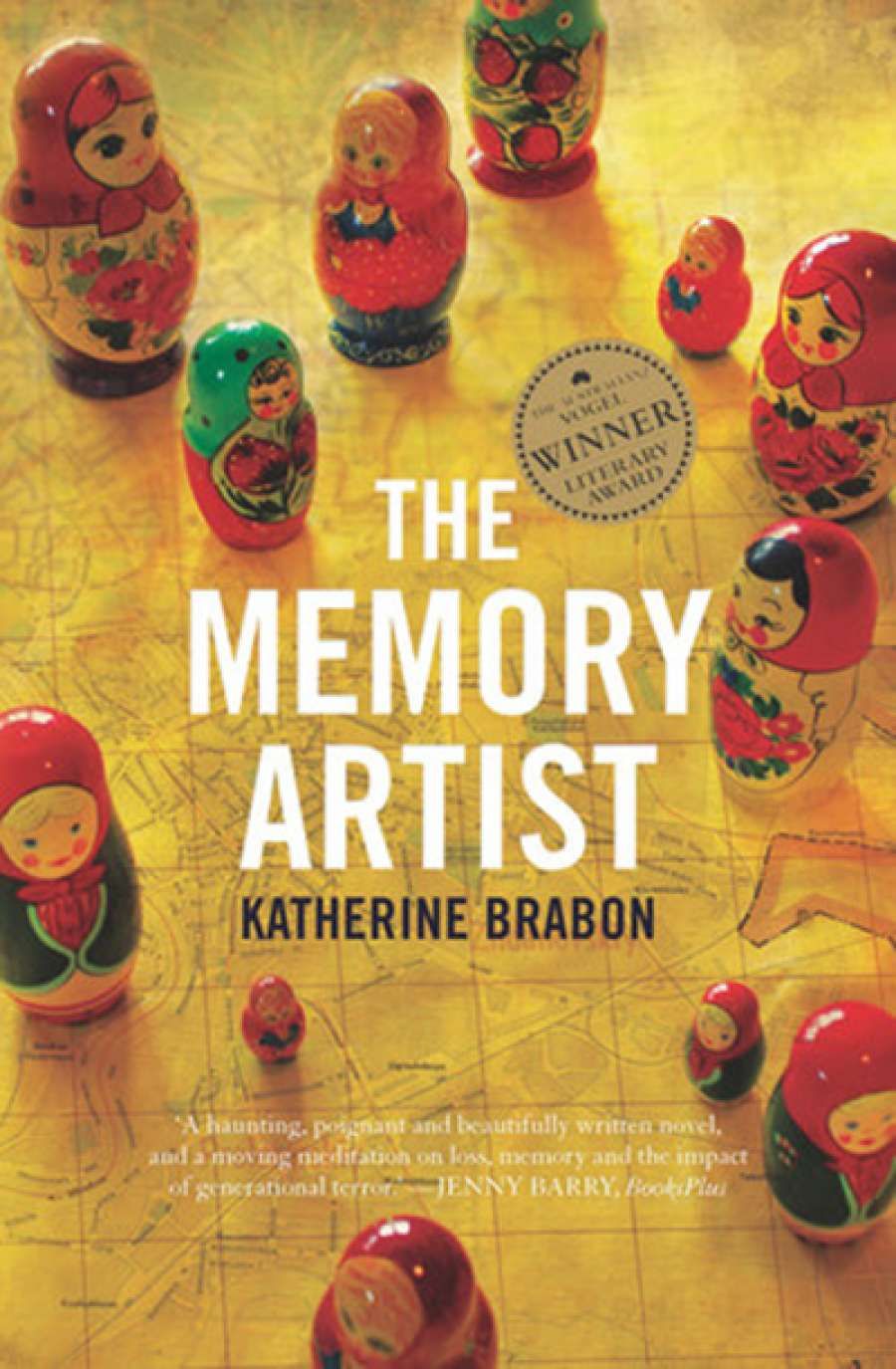

- Custom Article Title: Felicity Plunkett reviews 'The Memory Artist' by Katherine Brabon

- Custom Highlight Text:

For Pasha Ivanov, memory is 'a warped wound, with a welt or bruise that had arrived inexplicably late'. As the son of political dissidents in Moscow during Brezhnev's ...

- Book 1 Title: The Memory Artist

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin $29.99 pb, 300 pp, 9781760292867

The novel's structure, fluctuant and layered, shifts between Pasha's childhood, early adulthood, and present following the death of his mother. This reflects his sense of memory's imprints on his present, which feels provisional and flimsy to him. At thirty-four, he has a lover whose children he has never met, takes weeks to tell her that his mother has died and only reveals that he is a writer much later. Without a sense of the past, his present is hollow and uninhabitable.

As a writer, he attempts to make sense of the silenced and vanished. Central to this is the disappearance of his father. Around him many have suffered similar losses. Solitary, he thinks often about memory. From this arises a poetics of memory. Metaphors shift and turn. It is a wrack-strewn seafloor ('remnants of ships, wood, algae, seaweed, bones and belt buckles, while schools of fish, thick comets of silver, streaked through the debris as though they couldn't bear to look at it'), a palimpsest, then a journey on an underground train. Alongside this runs a cartography of memory, and a geometry.

As a child, Pasha senses that his life runs on two axes: the outside world, and the silence and secrecy of his world at home. Maps and mapping may release secrets of the past, but might as easily gesture towards haunted spaces of imagined futures, such as the maps Pasha discovers that locate 'ghostless ghost towns' of abandoned town planning. The extent of the mapped world is as vast as memory, gesturing relentlessly towards places one will never visit.

Brabon's novel won The Australian / Vogel's Literary Award for an unpublished manuscript by a writer under the age of thirty-five. The prize, first awarded in 1980 to Archie Weller, has discovered work by a number of distinctive writers who have gone on to publish other award-winning fiction, including Gillian Mears, Kate Grenville, Brian Castro, and Bernard Cohen.

Brabon's work was part of a PhD at Monash University. Its contemplation of memory suggests rich reading in the field of trauma and narrative. Memory and remembering beckon and elude Pasha. Stroking his lover's hair, he repeats the motion 'as though committing the act to memory'. He tells Anya that if she died he would 'move away, to the other end of the country', exhilarated by 'the starkness, the confessional feel' of words of love that Anya never returns. While he seeks to pin the present to the future with extravagant professions, she says little about how she feels, 'let alone about some imaginary future emotion'. The future recedes, 'forever not here'.

Katherine BrabonPasha hopes to write, with Anya, a history of the psychiatry that has affected their fathers. Pasha learns about the pseudo-diagnoses made to repress political dissidents, involving symptoms such as delusional aspirations and 'a heightened sense of self-empowerment'. Like his mother and the activists of his childhood, who write down what might otherwise be forgotten or destroyed, he wants to hold fast to vanishing histories, forging his bond with Anya at the same time. His quest is to trace the threads of submerged testimony, travelling in the dark underground towards reunion with the lost, including his father. He is aware that his condition is melancholic, but remains faithful to the artistry of commemoration. This recalls Jacqueline Rose's rejoinder to Freud's theory that melancholia is a failure to achieve mourning's desirable closure. Rose underlines the cruelty of a prescription of forgetting, asking: 'What is this love that, in mourning as opposed to melancholia, steadfastly, decidedly, works to extinguish itself?' She adds: 'What on earth does it mean to suggest that the living do not, should not, identify with the dead?'

Katherine BrabonPasha hopes to write, with Anya, a history of the psychiatry that has affected their fathers. Pasha learns about the pseudo-diagnoses made to repress political dissidents, involving symptoms such as delusional aspirations and 'a heightened sense of self-empowerment'. Like his mother and the activists of his childhood, who write down what might otherwise be forgotten or destroyed, he wants to hold fast to vanishing histories, forging his bond with Anya at the same time. His quest is to trace the threads of submerged testimony, travelling in the dark underground towards reunion with the lost, including his father. He is aware that his condition is melancholic, but remains faithful to the artistry of commemoration. This recalls Jacqueline Rose's rejoinder to Freud's theory that melancholia is a failure to achieve mourning's desirable closure. Rose underlines the cruelty of a prescription of forgetting, asking: 'What is this love that, in mourning as opposed to melancholia, steadfastly, decidedly, works to extinguish itself?' She adds: 'What on earth does it mean to suggest that the living do not, should not, identify with the dead?'

Yet Pasha's present is eclipsed by the past's dark energy and mystery. He identifies with the people Varlam Shalamov describes in Kolyma Tales (1978) as the dokhodyagi, or soon-to-be-dead. Memory's hold and Anya's quest to emigrate strand the young couple in a shadowy 'twilight of togetherness', he staring towards and she away from 'the dragging past'. He thinks that 'we are all merely fractured creatures, always in search of our story'. Our maps evolve, inscribed with 'every little failure, the things never done and the memories forgotten'.

This is a work of insightful exploration of Freud's Nachträglichkeit or afterwardsness. Pasha hovers, haunted and ghostly, at the edges of the present, walking alongside others caught in loss and searching for vanished histories. Occasionally, the weight and eloquence of Pasha's thoughts threatens to turn him from character into device. Ultimately, the focus of this impressive début is its anatomy of memory, rather than the life stories it engulfs.

Comments powered by CComment