- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

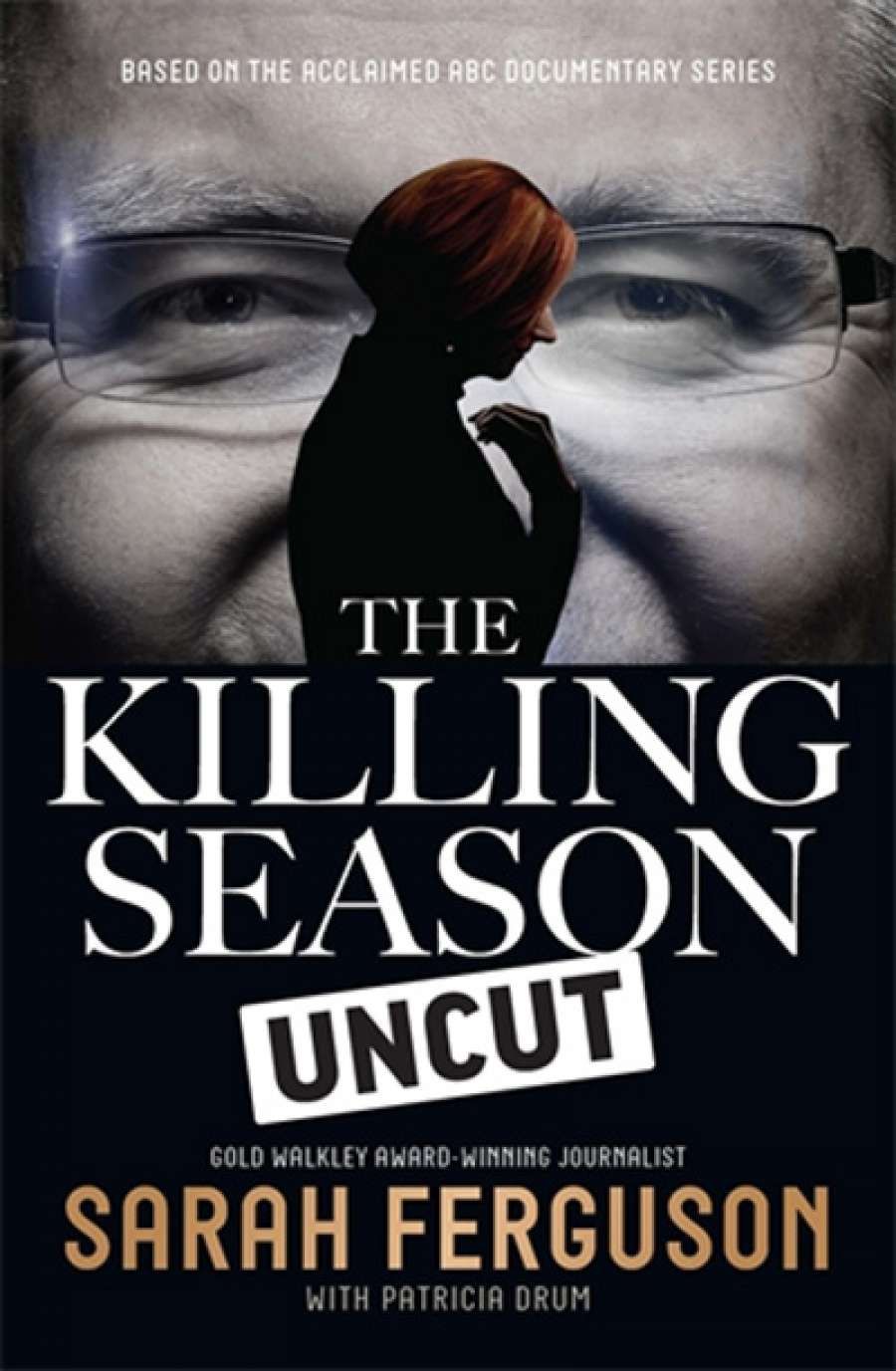

- Custom Article Title: Neal Blewett reviews 'The Killing Season Uncut' by Sarah Ferguson with Patricia Drum

- Custom Highlight Text:

Books have long provided fodder for films and television. Now films and television series, particularly documentaries, spawn books. The Killing Season Uncut is a ...

- Book 1 Title: The Killing Season Uncut

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $32.99 pb, 310 pp, 9780522869958

The documentary was a skilful blend of archival material combined seamlessly with imaginative reconstructions to provide dynamism, plus material from fifty-five identified on camera interviews. As the tough Ms Ferguson points out, there was no unsourced material: 'Anyone who wanted to shape the narrative had to appear in it, in full view where their colleagues could judge them and the truth of what they were saying.' The result was a commanding documentary which has rarely been rivalled in Australian political television.

By badgering, cajoling, and dining the politicians, and with the implicit threat that 'the narrative ... would belong to those who turned up', the formidable Ferguson assembled a stellar cast, including Rudd and Gillard, both of whom had been initially reluctant. There were, however, significant 'holdouts'. Despite valiant efforts Ferguson failed to woo Penny Wong. Yet Wong was Rudd's chief ally in the conflicted battle over what to do with the Carbon Pollution Reduction scheme in the first months of 2010, and her desertion of Gillard in mid-2013 was regarded by some as the point where Gillard's troops 'lost the majority'. The fabulously discreet John Faulkner remained discreet. Yet he holds the resolution to the contradictory versions of the fateful and fatal meeting between Rudd and Gillard on the evening of the 24 June 2010 challenge, and was the intermediary in murky negotiations between the Gillard camp and Rudd over Rudd's future as foreign minister during the 2010 election campaign.

Most disappointing was her failure to convince parliamentarians Mark Arbib and Bill Shorten, and the key apparatchik, National Secretary Karl Bitar, to participate. Yet these were the men who led the insurgency against Rudd in June 2010, mobilising his long-time enemies, sidelining most of the Cabinet, panicking marginal seat holders, and stampeding the caucus. Shorten was a special case. By the time of the interviews he was leader of the Labor Party, and while he had been instrumental in Gillard's elevation, his support had been a condition of Rudd's second coming. 'It suits the contemporary Labor narrative,' writes Ferguson, 'to say the challenge [to Rudd] was driven by Mark Arbib'. Around Shorten his colleagues form a protective 'phalanx'; their memories become 'hazy'. ' But,' as Ferguson makes clear, ' there were enough exceptions to place Shorten at the heart of the drama.'

What can a book of the series add to the immediacy and vividness of so successful a show? As it turns out, a lot. For one thing, more than half the interview material in the book did not appear in the documentary. Nor is this left-over stuff, merely detritus on the cutting room floor. Moreover, the documentary was inspired by television drama, and episodes included primarily for their dramatic effect do not appear in the book. One example is the catastrophic bushfires in Victoria in February 2009, though their exclusion from the book denies glimpses of Rudd in simpatico mode with the victims. On the other hand, the thoughtful, low-key finance minister, Lindsay Tanner, although quoted in the book, was not included in the documentary on the grounds that he 'wasn't inclined to provide answers that suited the tempo of the program'. The de-emphasis on the dramatic allows for a more analytic approach in the book.

However, this opportunity for analytic reflection does not overcome the major flaw both in the documentary and the book – the inadequate coverage of the decline and fall of Julia Gillard. Although Gillard served slightly longer as prime minister than Kevin Rudd, her prime ministership gets only one episode out of three in the documentary, and some seventy pages out of 300 in The Killing Season Uncut. This was the result of the dramatic imperative: 'the series had to be built around the Labor leadership change in 2010. Everything flowed towards and away from that cataclysmic event.' The drawn-out, agonising demise of Gillard cannot compare in dramatic terms with the late-night coup that brought down Rudd. The result of this imbalance is to weigh the scales against Gillard, the plotter, as against Rudd, the underminer.

Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard at their first press conference as leader and deputy leader of the Australian Labor Party on 4 December 2006 (photograph by Adam Carr, Wikimedia Commons)

Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard at their first press conference as leader and deputy leader of the Australian Labor Party on 4 December 2006 (photograph by Adam Carr, Wikimedia Commons)

The most invaluable aspect of the generally more analytic approach of the book is the intrusion of the presenter in the narrative. An astute interviewer, Ferguson now provides insights, not possible on the silver screen, into her interviewees. The Treasury Secretary, Ken Henry, 'was one of the stand-outs of the ... interviews. His answers were self-deprecating ... and he was able to praise Rudd and also approach him without rancour.' Greg Combet's interviews were 'candid, outspoken and enriched by an earthy invective'; Immigration Minister Chris Evans's 'most valuable quality [was] fairness'. By contrast, Treasurer Wayne Swan's 'antipathy towards Rudd suffused every aspect of the story he told'.

It is with the two protagonists that her insights are most comprehensive and telling. Their styles confirm what we know of them: Rudd was usually late, less efficient, and a bit disorganised; Gillard was punctual, efficient, precise. On the other hand, the 'engaging' and 'labile' Rudd, having 'a sharp instinct for how the media works', set out 'to master the interviews', whereas the 'guarded' and 'reserved' Gillard simply wanted to get through them. Rudd could be 'turgid'; Gillard 'opaque'.

Sarah FergusonFerguson sketches their arguments over the events of June 2010, which Rudd calls a 'coup' and Gillard, anodynely, the 'leadership change'. Gillard's rationale is essentially a managerial critique of Rudd's failure to cope governmentally in the first half of 2010, buttressed by what seems an exaggerated view of his mental health, which made him unfit for governing or electioneering. This is coupled with the claim that she did nothing to undermine him, covered up his defects, until at the very last moment, in the national interest and to avoid electoral defeat, she accepted the leadership of the insurrection which she had done nothing to initiate. Unwilling to concede any political flaws, apart perhaps from some inadequacies in delegation, Rudd provides essentially a moral critique: he was brought down by the overweening ambition of Gillard, allied with 'the bovver boys' of the party factions. Interestingly, post-June 2010 the arguments are reversed. Now it is Gillard who offers a moral critique of the 'bastardy' of Rudd's efforts, with his group of 'cardinals', to undermine her and to deny her any clear air. Rudd, by contrast, provides now a political critique – 'Julia had a frontal encounter with reality', and failed – while proclaiming his innocence of any plot to displace her.

Sarah FergusonFerguson sketches their arguments over the events of June 2010, which Rudd calls a 'coup' and Gillard, anodynely, the 'leadership change'. Gillard's rationale is essentially a managerial critique of Rudd's failure to cope governmentally in the first half of 2010, buttressed by what seems an exaggerated view of his mental health, which made him unfit for governing or electioneering. This is coupled with the claim that she did nothing to undermine him, covered up his defects, until at the very last moment, in the national interest and to avoid electoral defeat, she accepted the leadership of the insurrection which she had done nothing to initiate. Unwilling to concede any political flaws, apart perhaps from some inadequacies in delegation, Rudd provides essentially a moral critique: he was brought down by the overweening ambition of Gillard, allied with 'the bovver boys' of the party factions. Interestingly, post-June 2010 the arguments are reversed. Now it is Gillard who offers a moral critique of the 'bastardy' of Rudd's efforts, with his group of 'cardinals', to undermine her and to deny her any clear air. Rudd, by contrast, provides now a political critique – 'Julia had a frontal encounter with reality', and failed – while proclaiming his innocence of any plot to displace her.

Ferguson, and indeed the reader, struggle to adjudicate between these competing narratives. That the government was functioning poorly in 2010 is undeniable. There was a traffic jam over key issues, there was uncertainty as to where decisions were being made or not made, and the government gave an impression of drift. Ferguson pushes Ken Henry in to admitting the possibility of a coming 'train wreck', but he did not believe the circumstances justified the overthrow of the prime minister. Nor, despite the catastrophic fall in Rudd's personal poll rating following the postponement of the carbon reduction scheme, did most ministers believe the government would lose the coming election. There is no evidence that Gillard plotted against Rudd or canvassed support until the final hours. Yet without her the insurrection could not have succeeded, and her last-minute decision to lead it 'killed', as Anthony Albanese observed at the time, 'two Labor prime ministers'.

One final reflection. The Killing Season Uncut illuminates an extraordinary period of fratricidal strife within the Australian Labor Party. But the problem does not seem seasonal. For a generation now the Labor leadership has been a killing field. The critical date seems to have been the overthrow of the workmanlike Bill Hayden in February 1983 by the charismatic Bob Hawke under the slogan 'Whatever it takes', although the regicide of Hawke eight years later also has strong claims. (I confess to having opposed the first and been complicit in the second.) Before 1983 the ALP had never denied a second electoral opportunity to its leader, and in this case to one who had restored its fortunes after the débâcles of 1975 and 1977. Never before 1991 had the party torn down a ruling prime minister. (Billy Hughes, in the conscription crisis of 1916, is an exception to both these generalisations, though unlike Hawke he retained the prime ministership and, unlike Hayden, he had further leadership opportunities.) The statistics tell it all. In the eighty years to 1983, the Labor Party had eleven changes of leader, three of them occasioned by the death of the incumbent. In the thirty years that followed, Labor changed leaders on ten occasions, none of the changes resulting from the death of the incumbent.

It might be argued that in the past the ALP was too loyal to its leaders, for example H.V. Evatt, Arthur Calwell, even Gough Whitlam after the defeat of 1975. It is not a charge that could be levelled at the modern ALP. It has been apparent for some time that the party has lost its ideological compass in the swamps of neo-liberalism. After reading this tragic tale, one might ask if Labor has also lost its moral compass.

Comments powered by CComment