- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

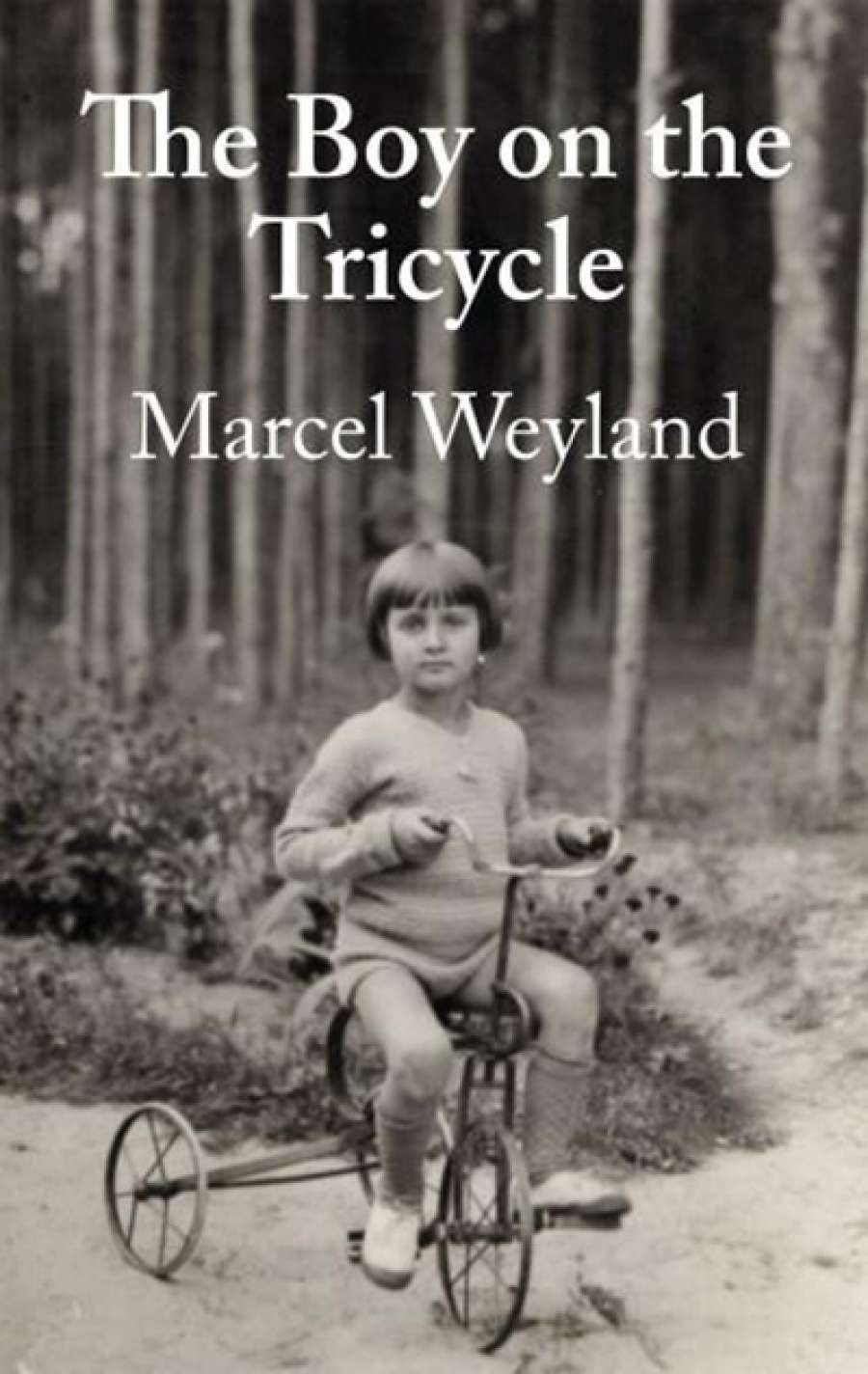

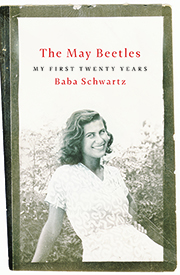

- Custom Article Title: Gillian Dooley reviews 'The Boy on the Tricycle' by Marcel Weyland and 'The May Beetles' by Baba Schwartz

- Custom Highlight Text:

Memoirs of Eastern European children of the 1920s could hardly be more different than this pair. The old age Marcel Weyland describes in The Boy on the Tricycle ...

- Book 1 Title: The Boy on the Tricycle

- Book 1 Biblio: Brandl & Schlesinger, $29.95 pb, 256 pp, 9781921556968

- Book 2 Title: The May Beetles

- Book 2 Biblio: Black Inc., $34.99 hb, 256 pp, 9781863958455

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

One can only imagine the stress and anxiety his parents must have suffered. For young Marcel, it appears to have been a splendid adventure. Shanghai is singled out for happy memories: 'It was vibrant, it was exciting, it allowed a freedom probably not available to [a young teenager] in pre-war Europe, perhaps because his adults were too preoccupied with matters of survival to restrict his freedom.'

Again, when the war ended, it was luck and the help of a sister that brought the family to Australia. Marcel's other sister, Maria, had married an Australian and could sponsor them; they moved to Sydney. 'The happiness was not unalloyed. News reports were now coming, horrifying and unbelievable ... a growing and heart-stopping awareness of the Holocaust.' Most of his family had died, but Weyland, never one to dwell on guilt and misery, immediately passes on to the news of those who have survived, and then proceeds to relate the rambling tale of his own life as an architect, husband, tourist, and, at a time of life when most have retired, a translator of Polish poetry. This last has been a source of great satisfaction and recognition ('of being made a fuss of and having metal things pinned to my breast'). We are left to wonder what happened to his sister Halina in later life; her 'decline' merely prompts a passing mention in one of the unremarkable travelogues which occupy much of the later part of the book.

There is no doubt that Weyland has a great capacity for enjoying life, and he imparts this in The Boy on the Tricycle. Perhaps at the root of this enjoyment is the sense of the extraordinary luck which he has enjoyed.

How different, though, was Baba Schwartz's experience of the war years. She was born around the same time as Marcel, in the Hungarian town of Nyírbátor, and lived there with her parents and two sisters for seventeen years, while Europe slowly disintegrated around them. Although they were not blind to the signs, they lacked the special combination of luck, insight, and good timing granted to Halina Weyland: the German invasion of March 1944 took them by surprise.

Baba Schwartz's memoir is inevitably harrowing, as she takes us from her home town to Auschwitz, with her immediate family and hundreds of others. She does not spare us the terror and degradation they were subjected to – the separation of families, the casual brutality, the routine humiliation.

A human being, especially one who has known comfort and kindness in the past, finds it a difficult thing to accept that other human beings can be blind to suffering. If you are despised and abused, it is natural to ask yourself why ... And yet my mother and sisters and I, and the hundreds of other women in the shed, accepted what was done to us promptly enough. For reasons that no Jew has ever properly comprehended, we were despised. We accepted it.

Her father was separated from them as they arrived at Auschwitz. She never saw him again, but the four women managed to stay together, and once again it was a woman's courage and ingenuity which allowed them all to survive. This story is full of genuinely heart-stopping moments – compulsive reading, especially towards the end – and Schwartz's mother, Boeske Keimovits, is the cool-headed and daring hero.

Baba Schwartz (photograph by Caitlin Muscat)Along the way, Schwartz surprises us often with small observations. In Auschwitz, this seventeen-year-old girl would chat with other girls about movies, books, clothes, and boys. 'Sometimes we sat together and sang songs we'd heard on the radio back home – often quite cheerful songs. Even at Auschwitz, we wished to sing.' Later, they encountered the German army in retreat. They had already been treated with kindness by ordinary German soldiers, but the defeated soldiers 'were more demoralised than us. We had survived so much and were seasoned by suffering.' Incredibly, the Keimovits women were now in a position to feed these 'poor, humiliated boys'.

Baba Schwartz (photograph by Caitlin Muscat)Along the way, Schwartz surprises us often with small observations. In Auschwitz, this seventeen-year-old girl would chat with other girls about movies, books, clothes, and boys. 'Sometimes we sat together and sang songs we'd heard on the radio back home – often quite cheerful songs. Even at Auschwitz, we wished to sing.' Later, they encountered the German army in retreat. They had already been treated with kindness by ordinary German soldiers, but the defeated soldiers 'were more demoralised than us. We had survived so much and were seasoned by suffering.' Incredibly, the Keimovits women were now in a position to feed these 'poor, humiliated boys'.

According to the blurb on the back of The Boy on the Tricycle, it shows how this boy 'survive[d] the Holocaust'. I suppose this is literally true, but 'escaped' would be less misleading. The young woman in The May Beetles, on the other hand, survived in the more usual sense: she suffered its effects on her body and her mind, she witnessed the death and the desolation, she lost close friends and family members, and she was reunited with others who had also endured. In Berlin after the war, she says, 'the two great themes of the stories we heard in the synagogue were "I have suffered" and "this I will now do"'.

There is no reason why Marcel Weyland should not write his memoir: his geniality and optimism might appeal to many. I will not say that his story matters less than that of Baba Schwartz. Both regard themselves and their families with some satisfaction, though in Weyland this can shade into smugness. There is a certain generosity of spirit in Schwartz: 'if I could bestow a gift on others, it would be to live as my family had lived before the great darkness.' Ethical questions aside, The May Beetles is better written, structured, and paced – perhaps owing to Robert Hillman's help in 'reshaping, reworking and refining' the narrative. And there is no denying the dark attractions of the Holocaust survival story, and its capacity to show, in all its familiar but unique particulars, how much human beings can endure without losing the essence of their humanity.

Comments powered by CComment