- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

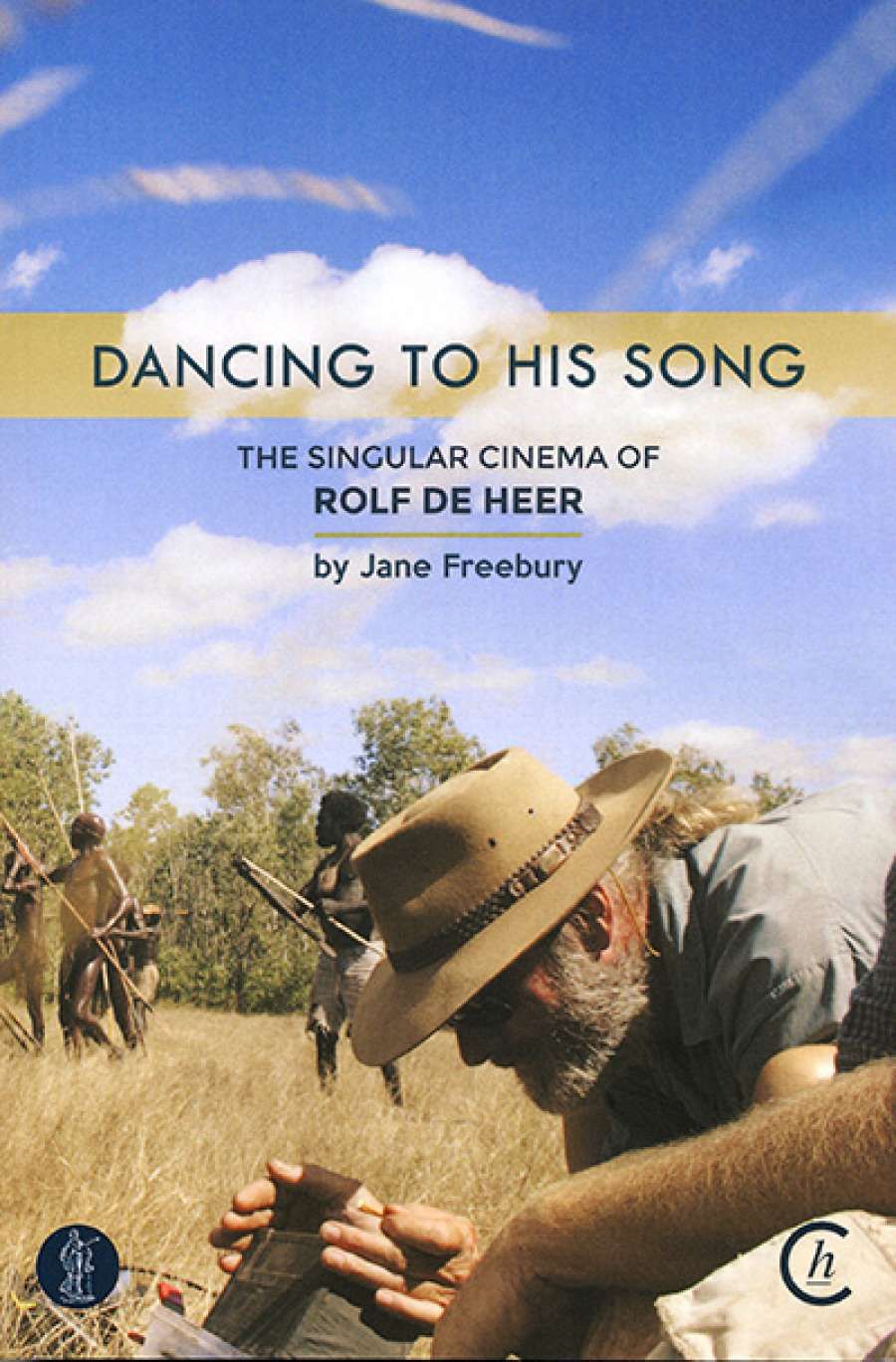

- Custom Article Title: Jake Wilson reviews 'Dancing to His Song: The singular cinema of Rolf de Heer' by Jane Freebury

- Custom Highlight Text:

More has been written about Rolf de Heer than about most Australian film directors of his generation, but Jane Freebury's Dancing to His Song contains ...

- Book 1 Title: Dancing to His Song

- Book 1 Subtitle: The singular cinema of Rolf de Heer

- Book 1 Biblio: Currency Press $49.99 pb, 364 pp, 9781925005585

Part of the achievement of Freebury's book lies in its exploration of the contradictions in de Heer's artistic identity. For most of his career, he has defined himself as a maverick, making his films locally on low budgets to preserve his independence. Yet he is also an avowed pragmatist, willing to build a narrative around whatever resources are available. He did without sync sound for Dr Plonk (2007), used his own home as the main location for The King Is Dead! (2012), and shot most of The Quiet Room (1996) on a single set, with his own young daughter in the lead role.

De Heer is commonly seen as a 'message' filmmaker, but there are contradictions here as well. Undeniably, his scripts tend toward blunt, eccentric sermonising; they denounce society's institutions, warn of environmental collapse, and defend marginalised groups. Yet, as Freebury points out, de Heer himself, as an interview subject, is much less outspoken, preferring to focus on the practical aspect of filmmaking rather than on any philosophical agenda.

Freebury speaks from experience, having conducted around thirty interviews with de Heer for Dancing To His Song, making this easily the most comprehensive study yet written of this important filmmaker. The format is conventional but thorough: Freebury covers each of de Heer's fourteen credited theatrical features in chronological order, supplying a synopsis, a critical overview, and a detailed account of production and reception.

A freelance journalist with a background in cinema studies, Freebury makes a handful of scholarly allusions that may baffle the non-specialist reader. She notes, for instance, that the plot of de Heer's Dingo (1990) is essentially 'the classic Proppian quest'. By and large, though, the writing is accessible and the approach straightforwardly descriptive; a habit of quoting extensively from other critics – including this writer – suggests a desire to multiply perspectives on de Heer's work rather than supply a single interpretative key.

Freebury's main weakness as a writer is a certain garrulousness; she tends to supply more information on any given topic than the reader knows how to use, and to let free association substitute for sustained argument. That said, her free associations are often provocative, especially when they imply that de Heer is closer to the mainstream of Australian cinema than has generally been supposed. Contemplating the outback landscapes of de Heer's early Incident at Raven's Gate (1988), she is reminded of 'the colonial dismay at an endless emptiness, the horror vacui, so unforgettably defined in Kotcheff's Wake in Fright'. In another passage, a potted history of the 'ocker' comedy establishes a surprising link between The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (1972) and de Heer's notorious Bad Boy Bubby (1993), two confrontational satires that follow a sexually disturbed man-child as he bumbles from one grotesque encounter to the next.

When she gets down to the nitty-gritty of close analysis, Freebury is often astute, teasing out how the complexity of de Heer's audiovisual rhetoric belies the simplicity of his themes: she has especially interesting things to say about the treatment of point of view in Bad Boy Bubby and The Tracker (2002), the two films that rank alongside the recent Charlie's Country (2013) as de Heer's best. Just as fascinating are the details about the making of Ten Canoes (2006), shot in Arnhem Land in collaboration with a local indigenous community. For de Heer, arriving at a storyline that would satisfy all concerned was a long and arduous process, all the more so as his collaborator David Gulpilil, originally envisaged as co-director, vanished a month before the shoot.

Rolf de Heer, David Gulpilil, and Molly Reynolds (source: National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, Flickr)

Rolf de Heer, David Gulpilil, and Molly Reynolds (source: National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, Flickr)

Gulpilil did, however, return to record the voice-over narration for Ten Canoes, as if he were in some sense the story's 'author'. This points to yet another aspect of the de Heer paradox: his reluctance to take credit for his own films, shifting attention to others or speaking as if they came into being of their own accord. Freebury has little patience with this pose: the production history sections of the book testify to the unusually tight control de Heer maintains at every stage of the filmmaking process, from the initial choice of subject-matter all the way through to the marketing campaign.

Indeed, one of the biggest strengths of Dancing to His Song – hinted at in the title – is its measured defence of a traditional notion of authorship. Freebury fully acknowledges the 'group effort' that goes into de Heer's films, but at the same time insists that their coherence ultimately depends on one man's vision. For a fond, detailed, and engaging account of that vision, you could do no better than turn to this book.

Comments powered by CComment