- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

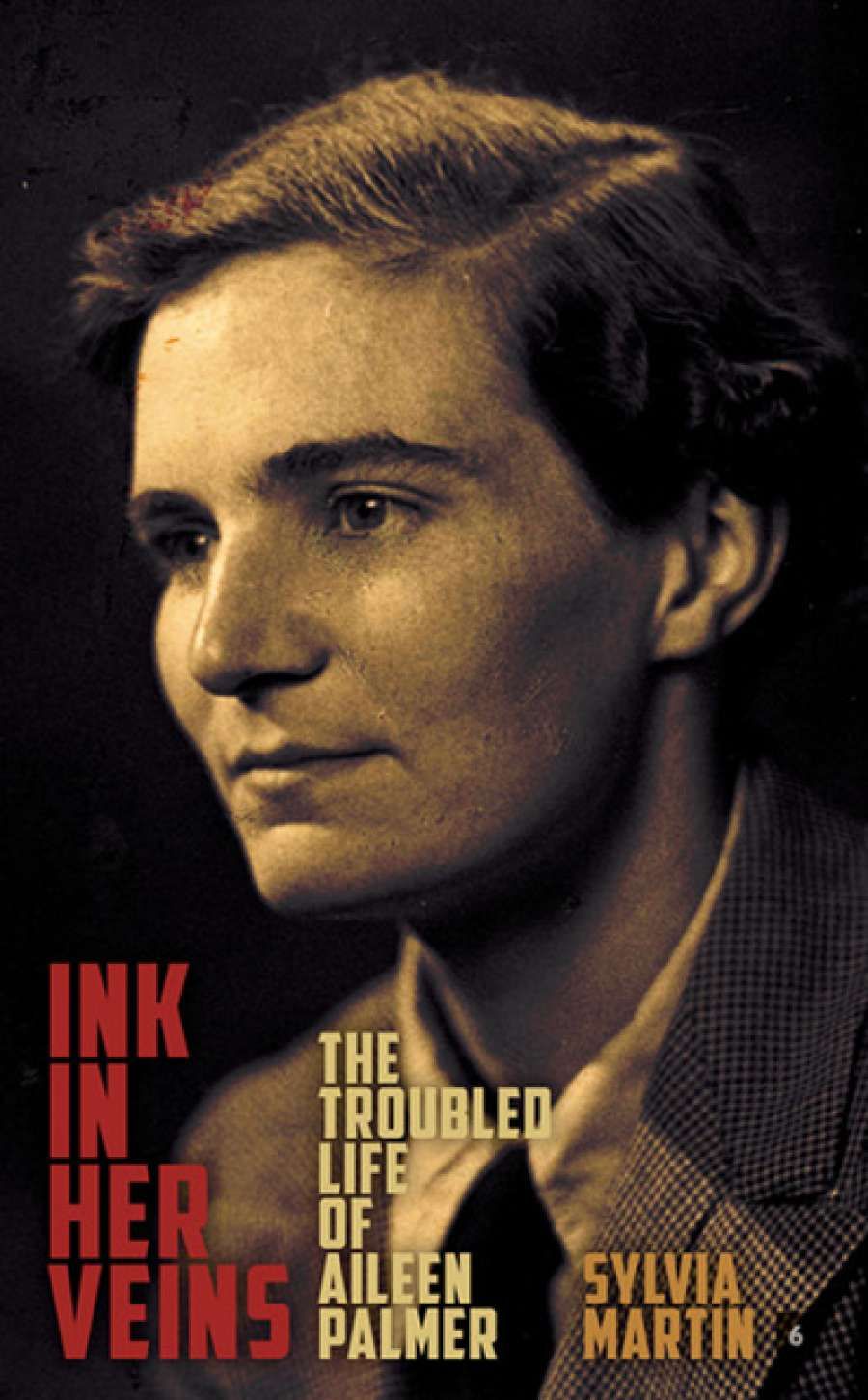

- Custom Article Title: Susan Lever reviews 'Ink in Her Veins: The troubled life of Aileen Palmer' by Sylvia Martin

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In her new biography, Sylvia Martin tells us that Aileen Palmer wanted to be remembered as a poet. Until now, she has been best known as the elder daughter of Vance ...

- Book 1 Title: ink in Her Veins

- Book 1 Subtitle: The troubled life of Aileen Palmer

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing $29.99 pb, 350 pp, 9781742588254

Aileen was born in London, shortly after the publication of her mother's first book of poetry – hence Nettie's concern about the possibility of 'ink in her veins'. World War I forced the family back to Australia, where the Palmers struggled to earn a living from writing. Through her childhood, they lived in rented cottages in Emerald, outside Melbourne, and Caloundra on the Sunshine Coast. In 1929 they moved back to Melbourne so that Aileen and Helen could attend their mother's alma mater, the Presbyterian Ladies College. Nettie also felt obliged to care for her ageing mother, now alone in the family house at Hawthorn. This demonstrates the sense of family duty that later restricted her daughters' lives.

Aileen was extraordinarily clever, going on to study several languages at the University of Melbourne. By the time she was seventeen she had joined the Communist Party of Australia, influenced by close friends of her parents Katharine Susannah Prichard, Christian Jollie Smith, and Guido Barrachi, and her uncle Esmonde Higgins. In 1935, the family set off for Europe to give their daughters experience of a wider culture. In London, Aileen mixed with international anti-fascist agitators and found her language skills in demand. She travelled to Vienna as the secretary to Dr Helene Scheu-Riesz, a socialist writer and publisher. She also, of course, witnessed firsthand the tensions between Nazis and socialists there. In 1936, with an unerring instinct for international crisis, the Palmers decided that a little town on the coast outside Barcelona would be a peaceful working retreat and they took Aileen with them. She was in Barcelona when a group of fascist rebels attacked the city, initiating the Spanish Civil War.

While her parents returned to Australia, Aileen was to spend most of the next two years working as a secretary and translator with the British Medical Unit and the International Brigades in Spain. Whenever she could, she wrote about her experiences in letters and diaries, with the idea of writing a novel after the war finished. Exhausted and depressed, she returned to London a few months before the signing of the Munich Agreement with Hitler. In January 1939, Aileen and a comrade from the International Brigades, Angela Guest, were arrested after throwing red paint on the doorstep of 10 Downing Street in protest at Chamberlain's policy of appeasement. When World War II broke out, Aileen stayed in London, driving ambulances during the Blitz and falling in love with other women. It was a dangerous and exciting life.

Vance, Helen in Nettie's arms and Aileen Palmer at Emerald, Victoria, 1918 (source: Palmer collection, National Library of Australia)When the war ended, Aileen was only thirty years old; reluctantly, she returned to Australia out of concern for her mother's health. By 1948 her erratic behaviour concerned her parents and sister so much that they arranged for her to be admitted to a psychiatric hospital. From then on, her life was a round of extreme psychiatric treatments (insulin-induced comas, electroconvulsive therapy, lithium) and returns home to recuperate and try to write. She remained a political activist in the Peace movement, translated the poetry of the Vietnamese revolutionary poet To Huu from French, and 'rendered' into English verse the prison diary of Ho Chi Minh from a basic literal translation of his Chinese calligraphy. Her one book of poetry, World Without Strangers, was published in 1964.

Vance, Helen in Nettie's arms and Aileen Palmer at Emerald, Victoria, 1918 (source: Palmer collection, National Library of Australia)When the war ended, Aileen was only thirty years old; reluctantly, she returned to Australia out of concern for her mother's health. By 1948 her erratic behaviour concerned her parents and sister so much that they arranged for her to be admitted to a psychiatric hospital. From then on, her life was a round of extreme psychiatric treatments (insulin-induced comas, electroconvulsive therapy, lithium) and returns home to recuperate and try to write. She remained a political activist in the Peace movement, translated the poetry of the Vietnamese revolutionary poet To Huu from French, and 'rendered' into English verse the prison diary of Ho Chi Minh from a basic literal translation of his Chinese calligraphy. Her one book of poetry, World Without Strangers, was published in 1964.

Growing up in the shadow of her literary parents, Aileen decided to become a writer at an early age. Martin relies on several of her unpublished novels and notebooks to speculate about the emotional detail of Aileen's life. None of her novels was published; her family, aware of her mental fragility, found her poetry disturbing. In her last decades, Aileen continued to write and rewrite autobiographical fragments in an attempt to retrieve the memories destroyed by psychiatric treatment.

She left much material for Martin to analyse and consider, and this biography gives an engaging account of the experience of a young woman caught up in the crises of major European wars. It provides a new perspective on Vance and Nettie Palmer and their circle of friends, and the context of their commitment to literature. Yet it also raises questions about the appropriate subjects of biography and its limits when confronting mental illness. For all her ambition, Aileen did not become a significant writer or public figure, and her last decades saw a sad decline from an active and adventurous young woman. Perhaps her parents and sister were too solicitous for her welfare or too conventional to acknowledge her sexuality, but after all these years a biographer cannot know. Martin has not retrieved a poet, only a suffering woman.

Comments powered by CComment