- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Custom Article Title: Alistair Thomson reviews 'Memory and Migration in the Shadow of War: Australia's Greek immigrants after World War II and the Greek Civil War' by Joy Damousi

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When we talk about the importance of Australia's remembered wartime past, we mostly think of home-front experiences or Australians who went away ...

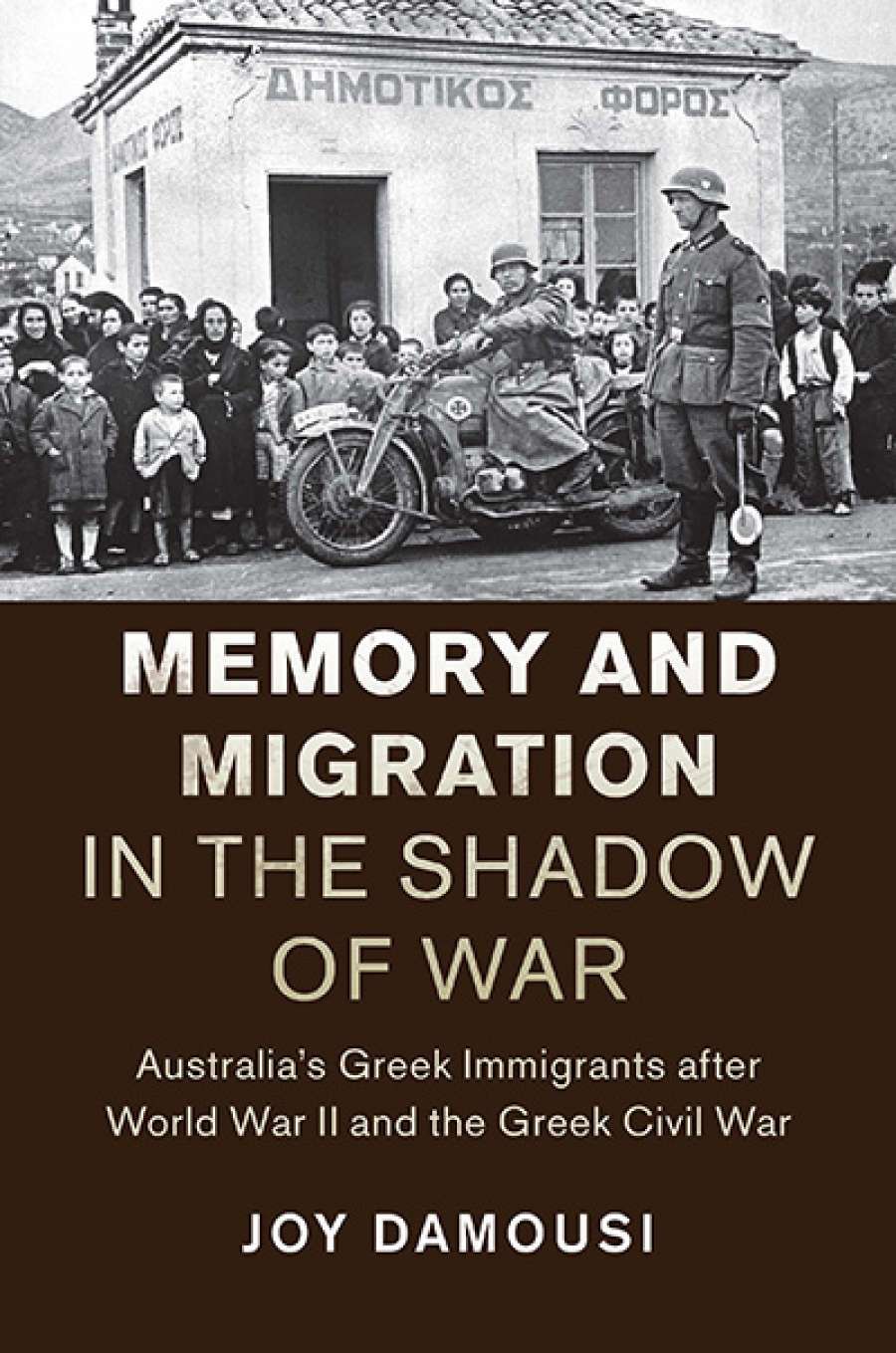

- Book 1 Title: Memory and Migration in the Shadow of War

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australia's Greek immigrants after World War II and the Greek Civil War

- Book 1 Biblio: Cambridge University Press $145 hb, 270 pp, 97811107115941

Damousi traces a long history of Greek Australians' relationship to war, starting with those who responded – by returning to fight, or by raising money and support – to the Balkan Wars in the early 1900s and the wars against the Ottoman Empire and then modern Turkey from 1915 to 1922. She notes how Australia often supported the Greeks in these conflicts, and as a World War II ally, but contrasts that support with the negative treatment of Greeks in Australia. After World War II, White Australia only grudgingly accepted Greek and other Mediterranean migrants because the British migrant supply was not sufficient to fulfil the need to 'populate or perish'. Damousi takes this familiar argument in a new direction, suggesting that Australian assimilation policy in the 1950s and 1960s was not only intended to absorb migrants within an 'Australian way of life', but also to extinguish migrant memories of the countries and cultures they had left, including migrant war memories. Though Damousi is certainly right about the aim to inculcate and maintain a homogenous Australian way of life, less evidence is presented about any self-conscious efforts to silence migrant war memory. In what ways, by what agencies, and in what sites and contexts was such silencing enacted and enforced? Perhaps migrants felt that their war stories, like their language, were not welcome, but I would have valued more evidence of this process, to weigh up against ample evidence of the ways in which the disabling psychological scars of wartime trauma prevented some Greek war survivors from articulating war memories.

A great strength of this book is its presentation and analysis of migrant testimony, mostly from oral history but also memoir and literature. This testimony recalls the excruciating story of Greece in the 1940s, of a violent German occupation and then a terrible Civil War. Especially poignant are the stories of the children, mostly from communist families, who were sent (or taken – the explanation is deeply politicised) to Eastern Europe to escape Civil War violence, and the difficulties faced as families tried to reunite after the war. Damousi reminds us that Australian activists, and the Australian Council of International Social Service, played an important role in reuniting some of these children with parents living in Australia.

Greek contingent in Melbourne, 1951 (source: National Library of Australia)

Greek contingent in Melbourne, 1951 (source: National Library of Australia)

Damousi also highlights how Greek Australian war memories influenced postwar migrant politics, especially among left-wing Greeks who become active in the labour movement, or who campaigned against the military junta that ruled Greece from 1967 to 1974. Not surprisingly, many of the postwar migrants had a communist background. As the losers in the Civil War, they fled both persecution and poverty. What is less clear in Damousi's book is the extent to which Civil War tensions were replayed in postwar Australia (there is the fascinating example of a Greek man who helped found the Heidelberg Alexander soccer club in Melbourne in 1958 'to "go against" Macedonia Preston – as a form of "symbolic revenge" for the death of a son killed in a Civil War bombing)'. It is clear that left-wing Greek migrants faced powerful conservative forces within the Greek community, including the Greek Orthodox Church, and parts of the Greek press, but it less clear from where these conservative agencies drew their support. Indeed, I wondered how war-related tensions in the postwar Greek Australian community might have impacted upon the articulation of war memory. While members of left-wing families seem to have been able to share memories of persecution, at first within their families, and now on the public record, the examples Damousi provides of families where Civil War memories are still repressed or suppressed seem to be mostly from those who were persecuted by the partisans and communists. Does a dominant cultural memory of the persecution of the Greek left make it harder for Greeks from the other side to share divergent memories?

Damousi's book reminds us that Australia's war history, and Australian war commemoration, needs to include all the wars that have so profoundly affected our population, including not just overseas wars fought by Australian expeditionary forces, but also wars experienced overseas by Australian migrants and colonial wars fought on Australian soil.

Comments powered by CComment