- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Russia

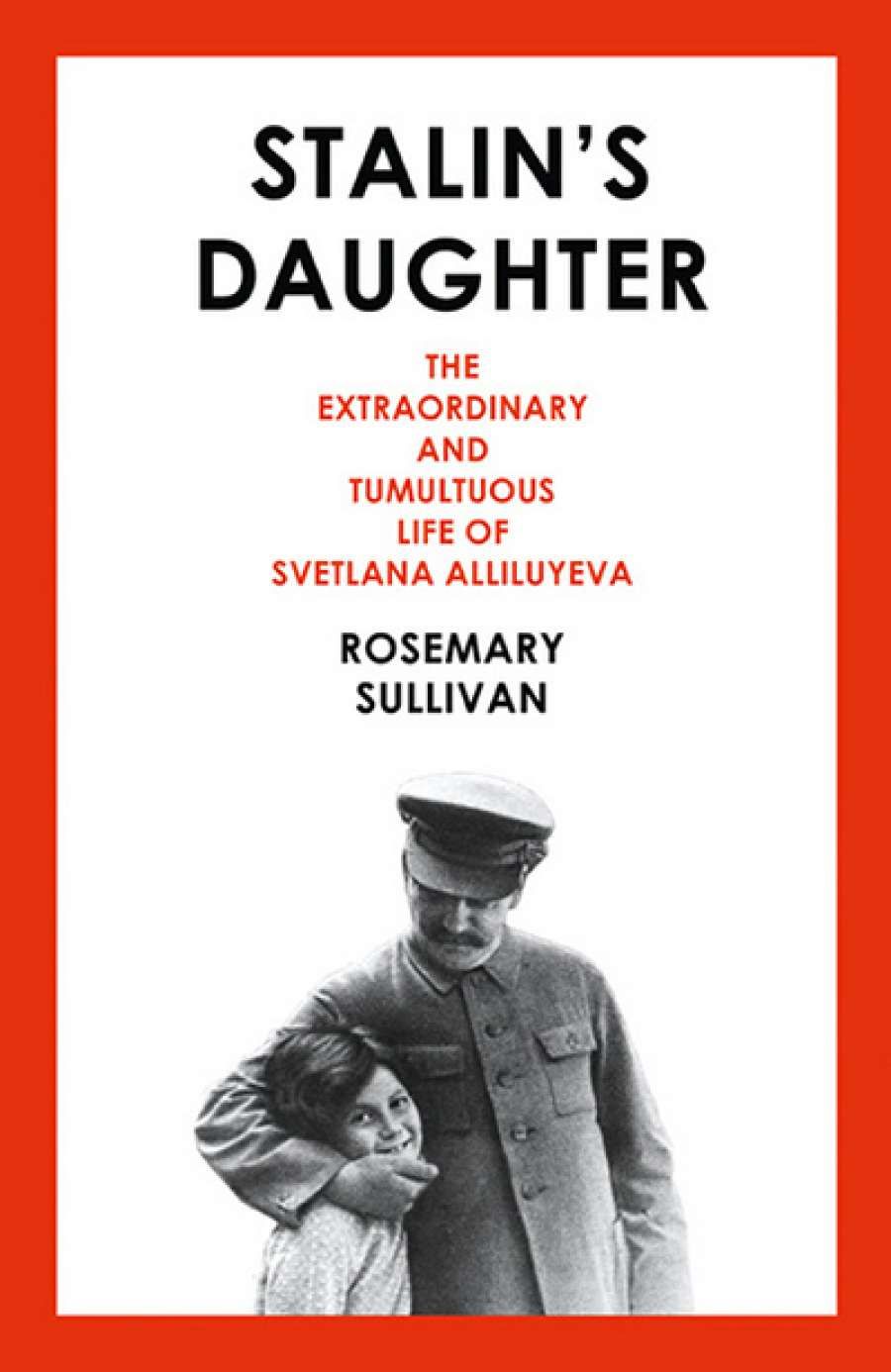

- Custom Article Title: Sheila Fitzpatrick reviews 'Stalin's Daughter: The extraordinary and tumultuous life of Svetlana Alliluyeva' by Rosemary Sullivan

- Custom Highlight Text:

Nobody would have expected an ordinary life for Stalin's only daughter, but Svetlana's life was extraordinary beyond any expectations. Her mother killed herself in 1932 ...

- Book 1 Title: Stalin's Daughter

- Book 1 Subtitle: The extraordinary and tumultuous life of Svetlana Alliluyeva

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $39.99 hb, 759 pp, 9780007491117

Svetlana was basically non-political, and her 1967 defection – taking refuge in the US Embassy in Delhi, where she had come to bury the ashes of her fourth common-law husband, the Indian journalist Brajesh Singh – was an impulsive personal rather than an ideological act. The Soviet leaders were furious and embarrassed, of course, but the old guard who had worked with her father and known her as a child – Khrushchev, Anastas Mikoyan, Klim Voroshilov and the rest of her 'uncles' – retained a soft spot for her regardless. When she re-defected, the new Soviet leaders (Yuri Andropov, and later Mikhail Gorbachev) treated her kindly, despite her refusal to accept the lavish apartments they offered, and even refrained from pillorying her when she decided to leave again; it was her two Soviet children and some of her old friends who were wary and cold. As for the United States, the natural tendency to exploit her initial defection was mitigated by the protection of Sovietologist George Kennan. But when, through his good offices in the 1980s, the CIA offered her a covert pension, she quixotically turned it down despite considerable financial hardship ('I have never been anyone's spy').

Clearly, Svetlana – born Svetlana Stalina, before changing her name to her idealised mother's Alliluyeva in 1957 and later, in America, becoming Lana Peters – was a woman of contradictions, which are well captured in Rosemary Sullivan's sympathetic and deeply researched biography. Modest and apparently shy, she could be suddenly imperious in the best Stalin manner. A lifelong romantic, she had a rich but generally disastrous love life.

Her first love affair at sixteen, with a much older Jewish celebrity journalist and film-writer, was angrily broken up by Stalin, and her lover served five years in a Gulag. On the rebound, she married another Jewish intellectual of whom Stalin disapproved (the father of her son, Iosif). After that broke up, she married Yury Zhdanov, son of one of her father's closest political associates, and they had a daughter, Katerina, but that marriage was another mistake and didn't even please her father as much as she had hoped. A cousin back from Gulag after the death of his mother and father (Stalin's friend and brother-in-law Svanidze) in the Purges was next on the list, followed by a passionate love affair with a Jewish poet and a briefer affair with Andrei Sinyavsky, the literary scholar whose conviction for anti-Soviet propaganda became a cause célèbre in the mid-1960s. Brajesh Singh, a much older man Svetlana met while he was in the Soviet Union for medical treatment, would have become her fourth husband if the marriage had not been forbidden by the new Brezhnev–Kosygin regime after the fall of 'Uncle Nikita' Khrushchev.

As this list indicates, the men Svetlana was prone to fall in love with were intellectuals, preferably of a literary bent. This pattern continued in the United States, where an affair with Russian-born Louis Fischer, a famous (and, in Sullivan's presentation, famously predatory) foreign correspondent caused her much grief. Reading Sullivan's book, I was startled to find that my own doctoral adviser in Oxford, the literary scholar Max Hayward, was also in her sights in the summer of 1968, when they were working together on the English translation of her memoirs (he fled back to Oxford, even more distracted and depressed than usual when we met again for supervisions in the autumn). As one of Hayward's friends said acidly, Svetlana really should have been able to see that 'he wasn't marriageable material'. But that was part of Svetlana's tragedy: she never could see that, and, once she discovered a spiritual affinity for a man, tended to jump immediately to thoughts of marriage. The American she did marry as her fourth husband, Wesley Peters, was a member of a kind of cult community dominated by Olgivanna, widow of the architect Frank Lloyd Wright, who is portrayed by Sullivan as a manipulating woman who valued Svetlana only for her celebrity and stage-managed the short-lived marriage.

Joseph Stalin with daughter Svetlana, 1935 (photograph by Eugene Zelenko, via Wikimedia Commons)

Joseph Stalin with daughter Svetlana, 1935 (photograph by Eugene Zelenko, via Wikimedia Commons)

Svetlana herself was a true Russian intellectual, passionate about literature, uninterested in money and possessions, expecting total commitment from her friends. She never ceased to miss the close, supportive community of Russian intellectuals she had experienced in Moscow as a young literary scholar in the years of the Thaw. Sullivan treats Svetlana's intelligentsia persona as a fluke, given her origins, but on this I would tend to disagree. It was one of the paradoxes of Stalinism that the children of Stalin's Politburo tended to avoid politics like the plague, and many of them, with their culture-valuing parents' blessing, went into the humanities or pure science. At Moscow State University, Svetlana Stalina studied history and American studies, along with the other two Kremlin Svetlanas (daughters of Vyacheslav Molotov and the disgraced Nikolai Bukharin), while her sometime boyfriend Sergo Beria (son of security policeman Lavrenty) studied physics, and her future husband, Yuri Zhdanov, took degrees in both chemistry and philosophy. In her American life, Svetlana, like many another Soviet intellectual, regarded herself as a writer, but this was a vocation rather than a career choice. As she struggled to provide for herself and her American daughter (by Peters), the one thing that never occurred to her was to try to get a job.

Comments powered by CComment