- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

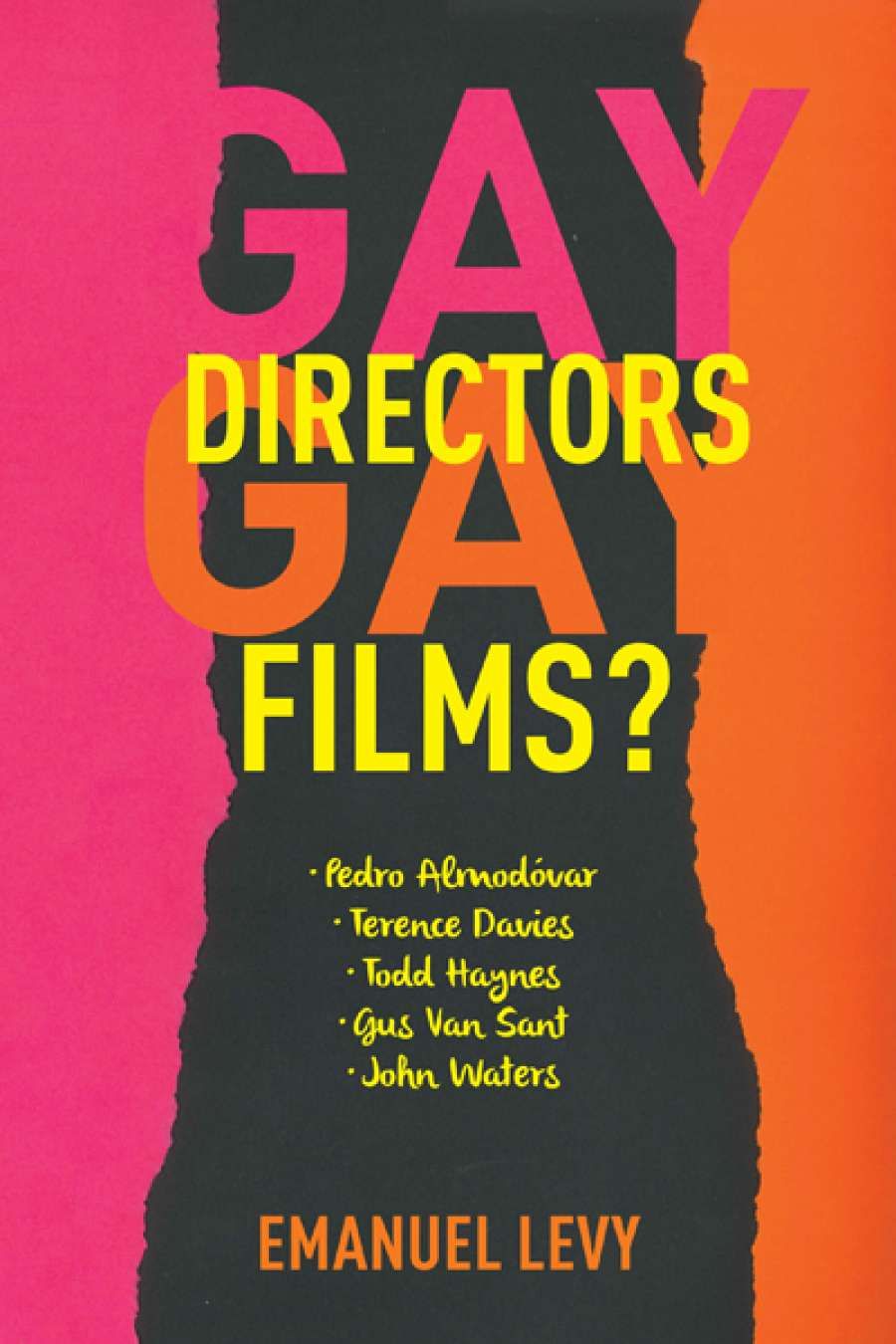

- Custom Article Title: Dion Kagan reviews 'Gay Directors, Gay Films? Pedro Almodóvar, Terence Davies, Todd Haynes, Gus Van Sant, John Waters' by Emanuel Levy

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Gay Directors, Gay Films?

- Book 1 Subtitle: Pedro Almodóvar, Terence Davies, Todd Haynes, Gus Van Sant, John Waters

- Book 1 Biblio: Columbia University Press (Footprint) $52.95 pb, 392 pp, 9780231152778

I put the cordon sanitaire around 'gay' because of my persistent sense that Levy's own critical evaluations pointed to 'queer' as the more appropriate term. Levy rejects 'queer', first as too politically radical and then as merely a 'hipper, cooler' term for 'gay'. He points out that, with the exception of Todd Haynes, all his subjects started their careers before the advent of queer theory. Fair enough, but throughout Gay Directors he is at pains to reiterate that the films play with categories of gender, sexuality, and desire in precisely the manner of post-1980s queer thought and politics. He seems to want it both ways.

Spain's enfant terrible Pedro Almodóvar opens the book and is the obvious favourite. Almodóvar's career is divided into four phases: 'Flamboyant Bad Boy' (quirky, insouciant), 'Mature Melodramas' (emotional), 'Masterpieces' (coherent melodramas), and 'Elegant Stylist' (too baroque and self-referential for Levy). All About My Mother (1999) and the autobiographical Bad Education (2004) are masterworks. No surprises here. Almodóvar apparently believes in the impossibility of enduring romantic love – a fascinating but unexplored thesis.

Pedro Almodóvar (photograph by Roberto Gordo Saez)Terence Davies, 'poet of the ordinary' and 'arguably Britain's greatest living filmmaker', is next up. Like all five auteurs, he fixates on tormented outsiders: The House of Mirth's (2000) Lily Bart, and Hester Collyer in The Deep Blue Sea (2012). A 'subjective memoirist', Davies' films are an 'exorcism' of the director's tortured Catholic working-class upbringing in the 1950s. Levy postulates that, although Davies has never acknowledged the influence of Marcel Proust, the ghosts of memory haunting his films suggests a 'Proustian philosophy'. This interesting idea isn't elaborated either.

Pedro Almodóvar (photograph by Roberto Gordo Saez)Terence Davies, 'poet of the ordinary' and 'arguably Britain's greatest living filmmaker', is next up. Like all five auteurs, he fixates on tormented outsiders: The House of Mirth's (2000) Lily Bart, and Hester Collyer in The Deep Blue Sea (2012). A 'subjective memoirist', Davies' films are an 'exorcism' of the director's tortured Catholic working-class upbringing in the 1950s. Levy postulates that, although Davies has never acknowledged the influence of Marcel Proust, the ghosts of memory haunting his films suggests a 'Proustian philosophy'. This interesting idea isn't elaborated either.

The next three auteurs are the Americans, and at least two of them are more satisfyingly drawn. Haynes is the most intellectual, with his early output influenced by the deconstructive impulses of the New Queer Cinema. Levy explains the relationship of his critical breakthrough film, Safe (1995), to the contexts of AIDs and therapy culture. Haynes is the cult filmmaker for the queer intellectual capable of recognising traces of Wilde and Genet. However, the reasons for Haynes's shift from deconstructive anti-realism to the lush Hollywood style of his later, adapted works – Far From Heaven (2002), Mildred Pierce (2011), and Carol (2015) – are unexplained.

Speaking of inexplicable adaptations, Levy has nothing unique to say about Gus Van Sant's critically loathed but intriguing career blip, the shot-by-shot remake of Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho (1998), one (queer) auteur's flop homage to another's (notoriously homophobic) masterwork. Van Sant, the 'poet of lost and alienated youth', is the most elusive of Levy's subjects. This is where the premise of 'the auteur', a director with a distinctive way of looking at the world starts to derail. Levy lists interesting themes (alienation, self-estrangement, transience) and presents curious paradoxes ('spontaneous yet iconoclastic'; 'intuitive but also very precise and decisive') but doesn't account for the weirdness of Van Sant's vision. As for gayness, Van Sant has made inscrutable comments on gay culture and identity and again, instead of imaginatively interpreting them, Levy simply concludes that 'the director has declined to problematize gay identity and sexuality in his films'.

Levy seems fond of John Waters's trash cinema, and the chapter on Waters is the most vivid portrait of the artist and the most holistic account of the way in which shifts in the culture have tamed the extremities of the director's work. Since the formerly shocking has become socially palatable, the golden age of trash that Waters spearheaded went into decline. Perhaps in general 'gay directors' and 'gay films', whatever these may be, are something of an anachronism? Levy doesn't speculate about this.

John Waters (photograph by Strevo, via Wikimedia Commons)He does, however, list commonalities in the book's conclusion. These include challenging societal taboos, representing marginal identities, innovative aesthetics, and an oscillation between the arthouse and the mainstream. Most of the quintet (except Van Sant) have a 'predilection for prominent and sympathetic female protagonists'. All have profited from the rise of queer and independent film festivals, and all seem to have been influenced by 'the damned poets' Rimbaud and Genet.

John Waters (photograph by Strevo, via Wikimedia Commons)He does, however, list commonalities in the book's conclusion. These include challenging societal taboos, representing marginal identities, innovative aesthetics, and an oscillation between the arthouse and the mainstream. Most of the quintet (except Van Sant) have a 'predilection for prominent and sympathetic female protagonists'. All have profited from the rise of queer and independent film festivals, and all seem to have been influenced by 'the damned poets' Rimbaud and Genet.

But what of gayness? What do these crossovers indicate about this sexual category and its particular cultures? With its question mark, Levy's title promises something about 'a distinctly gay gaze and a uniquely gay sensibility', which are 'intriguing' notions, as he writes, and properly aesthetic and historical ones. After all the detailing, it is as if Levy was too exhausted to say what these correspondences might actually mean.

Gay Directors, a comprehensive account of five remarkable careers in film, is burdened by its exhaustiveness. The net effect is a kind of critical sterility, which is odd coming from a veteran critic. Some university presses increasingly favour 'crossover' books that speak to broader audiences. This one may exemplify the inherent risk in this: books that don't speak satisfyingly to anyone.

Comments powered by CComment