- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Colin Nettelbeck reviews 'After the Circus' by Patrick Modiano

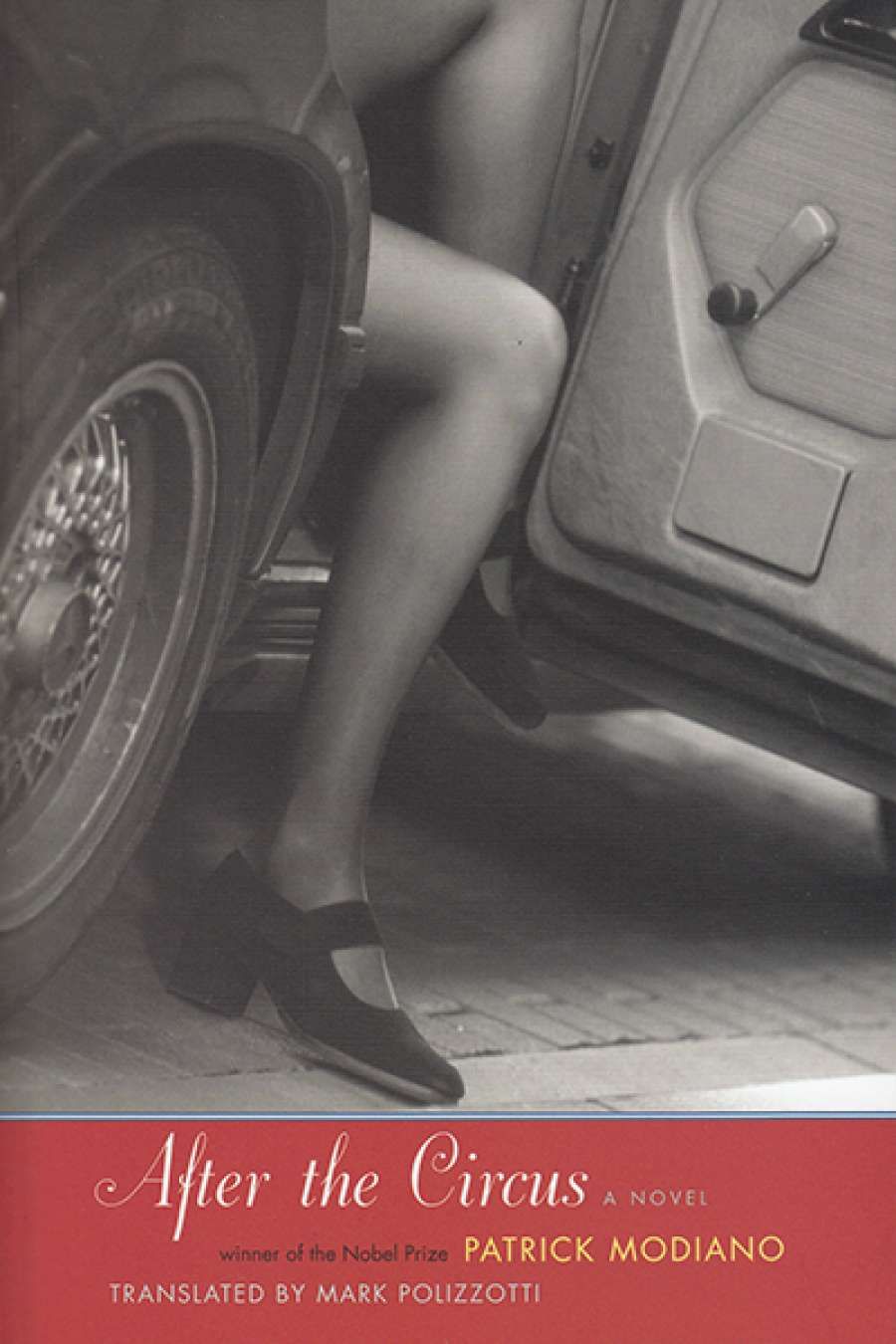

- Book 1 Title: AFTER THE CIRCUS

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press (Footprint) $28.95 pb, 197 pp, 9780300215892

In its portrayal of the nocturnal and the autumnal, After the Circus is a good companion for the Modiano translations recently published by Text Publishing – Little Jewel (Penny Hueston) and Paris Nocturne (Phoebe Weston-Evans). There, too, we find the blurring of identities, similar kinds of unresolved quests (determined but ultimately futile), the self-deprecating irony, the same sense of being left, after the reading, with an ambiguous glossy surface that, like a Rothko painting, will only yield its deeper truths to a careful effort of contemplation.

Patrick Modiano in 2014 (photograph by Frankie Fouganthin, via Wikimedia Commons)Modiano's work is becoming more widely known in the English-speaking world, thanks to the burst of high-quality translations that have followed his 2014 Nobel Prize (those of Polizzotti, Hueston, and Weston-Evans among them). There persists a danger that his oeuvre, which has grown organically since the publication of La Place de l'Etoile in 1968, may remain misunderstood: entering the opus through a middle- period work like After the Circus is a bit like reading Proust's The Captive without knowing Combray or Swann's Way – definitely not a meaningless experience, but one in which many of the keys to understanding and continuity are missing.

Patrick Modiano in 2014 (photograph by Frankie Fouganthin, via Wikimedia Commons)Modiano's work is becoming more widely known in the English-speaking world, thanks to the burst of high-quality translations that have followed his 2014 Nobel Prize (those of Polizzotti, Hueston, and Weston-Evans among them). There persists a danger that his oeuvre, which has grown organically since the publication of La Place de l'Etoile in 1968, may remain misunderstood: entering the opus through a middle- period work like After the Circus is a bit like reading Proust's The Captive without knowing Combray or Swann's Way – definitely not a meaningless experience, but one in which many of the keys to understanding and continuity are missing.

Take, for example, the historical context of the novel. Set in the 1960s, but written at the beginning of the 1990s, it bridges two particularly gloomy periods of France's recent history: the messy end of the Algerian War (and with it not just the dissipation of France's identity as a global colonial power, but the beginning of large-scale Islamic immigration); and the start of the public trials of former Vichy officials for crimes against humanity, which eventually led to President Chirac's famous 1995 acknowledgment of France's responsibility for the deportation of 75,000 Jews during World War II. This background is only occasionally explicit in the text, and readers unfamiliar with it might not notice it at all, other than as a kind of ominous space that looms behind the characters' thoughts and actions as the story unfolds. Those who know Modiano, however, are likely to be alert to the glancing allusions scattered through the work, partly for the fun of a game that the author sets up as a kind of tease, and partly because there are almost always hidden meanings which, once revealed, add density and depth not evident in the narrative lines. The name 'Bousquet', which has brought the narrator to the attention of the police, surely refers to René Bousquet, the powerful French chief of police in Nazi-occupied Paris, who, at the time of the writing of After the Circus, had been indicted for his role in the infamous round-up of Parisian Jews in July 1942 – only to be assassinated in suspicious circumstances just before the trial. Bousquet's closeness to François Mitterrand, who was nearing the end of his second presidential term when After the Circus appeared, has never been fully elucidated, but the intimations of top-level corruption and obfuscation are impossible to avoid. In the novel, this whole episode is reduced to an apparently throwaway name, but Bousquet's story, like that of the narrator's parents, forms part of a shadowy socio-political synapse related to the French experience and memory of the World War II dark years and their sequel, all of which has been treated more openly by Modiano in his earlier work.

René Bousquet (third to right) at a French-German Besprechung in Marseille, 1943 (photo courtesy of Bundesarchiv, Bild, via Wikimedia Commons

René Bousquet (third to right) at a French-German Besprechung in Marseille, 1943 (photo courtesy of Bundesarchiv, Bild, via Wikimedia Commons

Modiano's recourse to echoes is not a mere device. It corresponds to a tragic vision of a world – not limited to its French setting – that seems to be running out of time. His constant turning to the memory of youth is not mere nostalgia, either: it is a way of seeking the energy to fulfil his belief that a writer's dignity and duty lie in telling the story to the very end, with all the art he can bring to it.

Comments powered by CComment