- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Economics

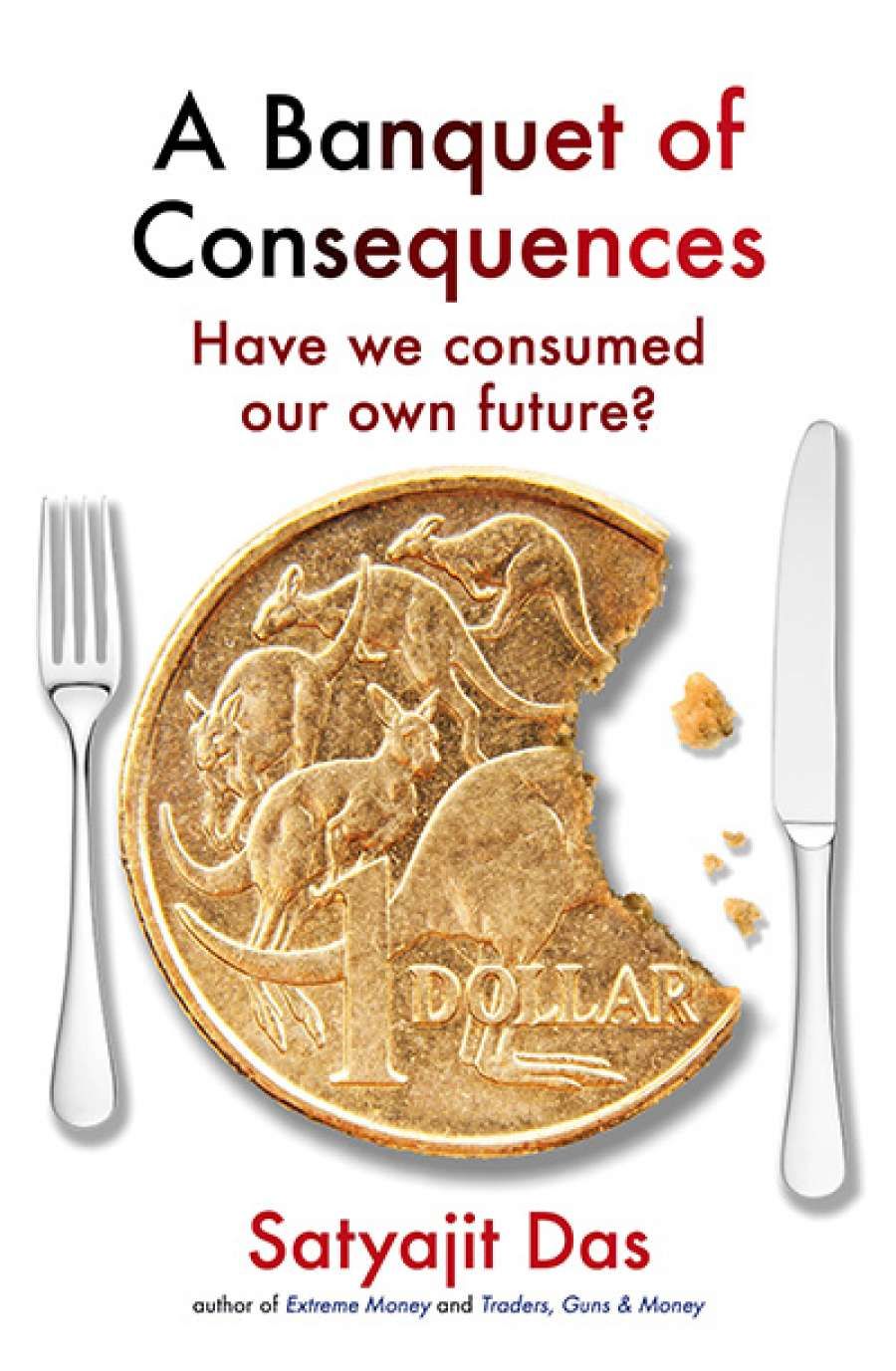

- Custom Article Title: Reuben Finighan reviews 'A Banquet of Consequences: Have we consumed our own future?' by Satyajit Das

- Book 1 Title: A Banquet of Consequences

- Book 1 Subtitle: Have we consumed our own future?

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking $34.99 pb, 352 pp, 9780670079056

Satyajit Das (photograph by Thomas Gallane Photography)Das is aware of this history and notes the challenges facing economists who would play Nostradamus. The phenomenon of modern economic growth is a huge global experiment of unfathomable complexity, and we mere mortals must be content with educated guesses as to how it might end. Humility, therefore, is an asset to the serious macroeconomic commentator. Yet Das quickly forgets that he, too, is a mortal, and as soon as he is done mocking those economists bogged in the mire of hubris he charges headlong into it. A Banquet of Consequences brooks no uncertainty. The first pages set the tone by channelling George Orwell: 'In a time of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.' Das, thus, is to be our revolutionary. In a world of saccharine lies, where even academics are corrupted, he will tell the truth about where the global experiment is taking us.

Satyajit Das (photograph by Thomas Gallane Photography)Das is aware of this history and notes the challenges facing economists who would play Nostradamus. The phenomenon of modern economic growth is a huge global experiment of unfathomable complexity, and we mere mortals must be content with educated guesses as to how it might end. Humility, therefore, is an asset to the serious macroeconomic commentator. Yet Das quickly forgets that he, too, is a mortal, and as soon as he is done mocking those economists bogged in the mire of hubris he charges headlong into it. A Banquet of Consequences brooks no uncertainty. The first pages set the tone by channelling George Orwell: 'In a time of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.' Das, thus, is to be our revolutionary. In a world of saccharine lies, where even academics are corrupted, he will tell the truth about where the global experiment is taking us.

His vision is a dark one. We should abandon all hope that macroeconomic policies can save us and embrace a sharp reduction in economic activity. In Das's frugal future, communal living will be the norm, air conditioning banned, air travel heavily restricted, electricity 'rationed' and so on – an austerity much harsher than that currently visited upon Greece.

To justify such asceticism, delivered with such bombast, Das needs to show that he sees something that others have overlooked. Das needs to prove that this era is different, that it is not just another case of 'boom and bust', and that the limits to growth have finally been reached.

Is this time different? To make the case, A Banquet of Consequences details the global economic trends that are shaping our era. His vision is wide and compelling. Soaring inequality is described with an awareness of its profound human impact. Recent macroeconomic puzzles, like slowed productivity growth and the long trend towards low interest rates, are given their due. Das explores the many reasons to worry that the BRICS – the large emerging economies of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa – will be stuck in the 'middle income trap' that prevents many emerging economies from catching up with the West.

BRICS heads of state and government at the 2014 G20 summit (photograph by kremlin.ru, via Wikimedia Commons)

BRICS heads of state and government at the 2014 G20 summit (photograph by kremlin.ru, via Wikimedia Commons)

These trends alone, however, are insufficient to support Das's austere policy prescriptions. To make his case, he needs to overcome some much more influential voices than himself – to name a few, Nobel laureate Paul Krugman, former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, and UK central banker Andrew Haldane. The problem is that these macroeconomic luminaries begin with the same economic trends as Das, but their analyses are deeper, and they propose the exact opposite remedy.

Possibly recognising the scale of the challenge, Das avoids them. He acknowledges that Summers advocates increased public investment rather than the austerity that he would prefer, but brushes this off with an aphorism: 'Problems in economics are always the same; it's the answers that are different.' This sheds no light, but allows him to return to railing against debt. Too often when the analytic going gets tough, out comes another dubious aphorism, or a quotation from a middling financier or German playwright, to serve as an escape hatch. This makes for a frustrating read. A Banquet of Consequences could easily have been a better book if Das had moderated its ambition. Das's summary of recent trends is not deep, but it is effective. His macroeconomic analysis, however, is not sophisticated enough to support the conclusions, and his revolutionary truth becomes the falsehood that undermines the book.

Perhaps Das's pessimistic intuitions are sound, even if his analysis is not. Perhaps this time is different. But this book does not shed light on the matter. We will have to wait and see how the experiment plays out.

Comments powered by CComment