- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Suzanne Falkiner reviews 'Outback Penguin: Richard Lane's Barwell diaries' edited by Elizabeth Lane et al.

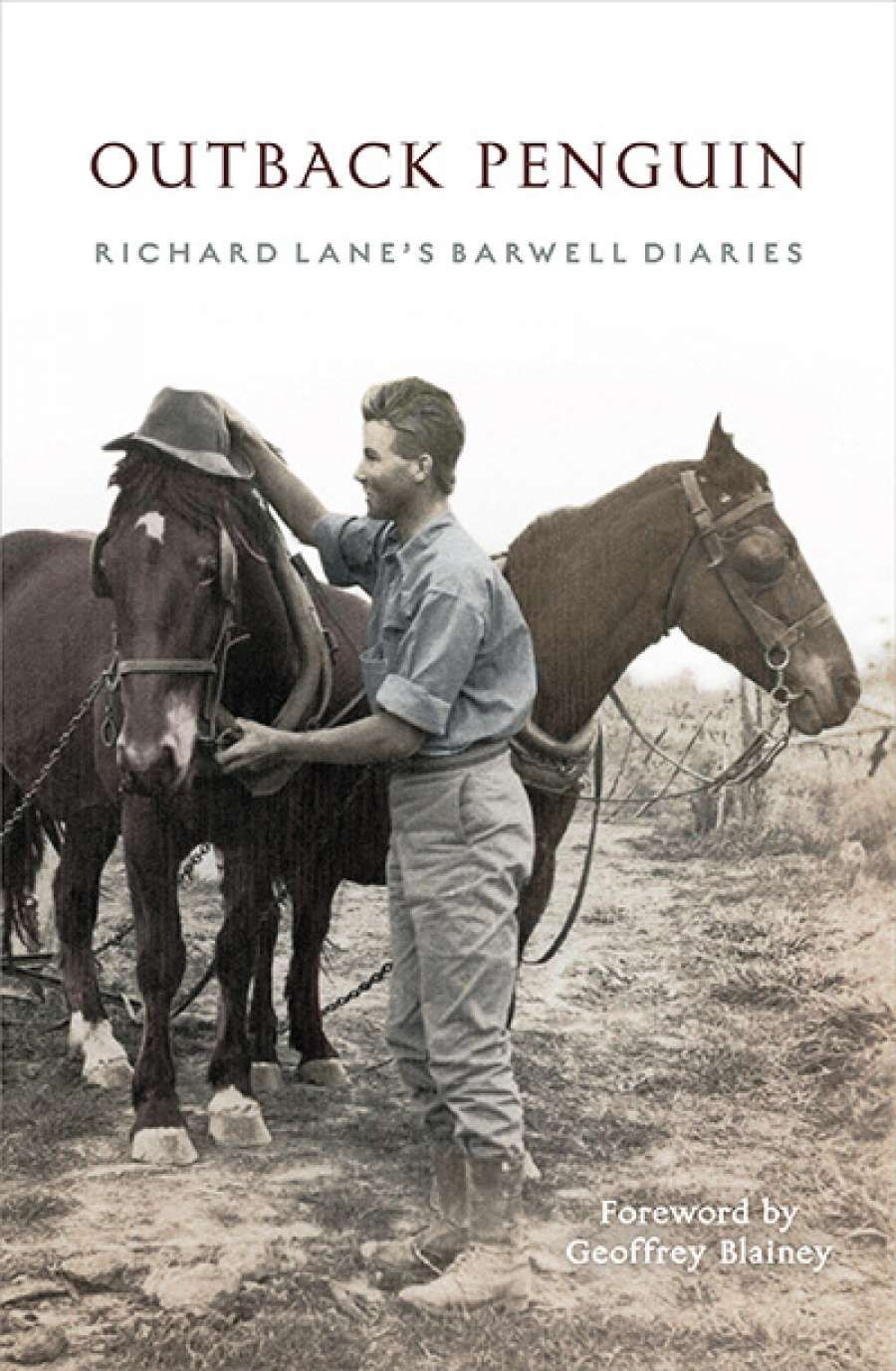

- Book 1 Title: Outback Penguin

- Book 1 Subtitle: Richard Lane’s Barwell Diaries

- Book 1 Biblio: The Lane Press (Black Inc.), $49.99 hb, 448 pp, 9781863958172

Betty and Richard Lane visiting Renmark on their honeymoon in July 1948Once in South Australia, during periods of isolation and homesickness, this one-sided conversation becomes a solace for loneliness and a relief from the monotony and exhaustion of farm work. Much must be read between the lines, as Lane does not wish to distress his beloved family. His first posting, on a twenty-two-acre soldier-settlement block near Renmark, where he is obliged to live in squalid conditions and work from sunrise until well after dark, lasts three months; then he asks to be released. His second position is more amenable, but in the lead-up to the Depression it costs South Australian grape-growers more to harvest their dried fruit than the market returns. His new employer, though kindly, absents himself for weeks, leaving his young apprentice in charge; Richard must cook and clean for himself while running the farm single-handedly.

Betty and Richard Lane visiting Renmark on their honeymoon in July 1948Once in South Australia, during periods of isolation and homesickness, this one-sided conversation becomes a solace for loneliness and a relief from the monotony and exhaustion of farm work. Much must be read between the lines, as Lane does not wish to distress his beloved family. His first posting, on a twenty-two-acre soldier-settlement block near Renmark, where he is obliged to live in squalid conditions and work from sunrise until well after dark, lasts three months; then he asks to be released. His second position is more amenable, but in the lead-up to the Depression it costs South Australian grape-growers more to harvest their dried fruit than the market returns. His new employer, though kindly, absents himself for weeks, leaving his young apprentice in charge; Richard must cook and clean for himself while running the farm single-handedly.

Innocent and good-hearted, prepared to think well of people even despite the evidence, by his own account Richard has little interest in girls, or grog, but he has a marked fascination with motor vehicles, of which he develops an almost encyclopedic knowledge. With an aptitude for their workings, he quickly develops the skills of a bush mechanic, inventively mending tyres on an old Ford with fencing wire and 'gaiters' (or reinforced patches), for his impoverished boss, who prefers to patch a leaking tyre twelve times over several days before conceding the need for a new one. When Withers is unable to pay his wages, a new vocational detour beckons – as usual, with no financial reward – when he branches out into 'track' driving, or conveying paying passengers by car the 170 miles on bush tracks between Renmark and Adelaide. Having lost his accumulated savings in this venture, he heads for Sydney by coastal steamer to visit new friends at a more prosperous rural property, Millamolong, near Bathurst. This in turn leads to a new job, as sole jackaroo on a run-down sheep station at Coonabarabran.

Penguin and the Lane Brothers (published by Black Inc.)Framed by Geoffrey Blainey's foreword and a workmanlike introduction by Elizabeth Lane, the writer's daughter, the book is a valuable social history of small farming in the period, but for many readers it will be of most interest as a portrait of the adult Richard Lane. As Stuart Kells has outlined more fully in Penguin and the Lane Brothers (2015), his well-researched account of the true story behind the Penguin publishing legend, Richard was the second of the three Williams brothers who collectively changed their name to Lane and founded Penguin Books in Britain. Richard Lane would later move back to Australia with his Australian wife and take over the management of Penguin Australia after Geoffrey Dutton, Max Harris, and Brian Stonier had jumped ship, partly in frustration at the perfidy and obstruction of Richard's older brother, Allen.

Penguin and the Lane Brothers (published by Black Inc.)Framed by Geoffrey Blainey's foreword and a workmanlike introduction by Elizabeth Lane, the writer's daughter, the book is a valuable social history of small farming in the period, but for many readers it will be of most interest as a portrait of the adult Richard Lane. As Stuart Kells has outlined more fully in Penguin and the Lane Brothers (2015), his well-researched account of the true story behind the Penguin publishing legend, Richard was the second of the three Williams brothers who collectively changed their name to Lane and founded Penguin Books in Britain. Richard Lane would later move back to Australia with his Australian wife and take over the management of Penguin Australia after Geoffrey Dutton, Max Harris, and Brian Stonier had jumped ship, partly in frustration at the perfidy and obstruction of Richard's older brother, Allen.

In the latter part of the diary, Richard comments to his family about his jottings: 'I could go on for hours, but what I write is of no interest to anyone save yourselves ... if only I could writes something that would interest someone who did not know me, I would start tomorrow.' There are moments when the reader finds herself agreeing with this self-assessment. Laborious descriptions of car trips, sunsets, lists of prices for local commodities, and the author's reflections on the fact that he has nothing worthwhile to write about, weigh heavily.

Like a cinematic scene shot in real time, the editors have evidently decided to cut or abbreviate nothing in this chronological sequence of primary documents, which includes correspondence with Barwell scheme officials. In addition, the text is littered with unglossed names and sparsely noted events that, with no further background, mean little to the virgin reader. Occasional footnotes, or detailed linking paragraphs, might have assisted here.

Yet, in some ways, this unclutteredness is the book's strength. We become aware of history taking place through a life as it is lived; and of the boredom, cultural impoverishment, and frequent futility of indentured labour on untenable rural holdings. Outside the scope of this book, within a few years the Barwell scheme would be subjected to a government inquiry into the mistreatment of its boy migrants.

Richard – no shirker of manual hard work, no matter how thankless – eventually concludes (as have most of those around him already) that his heart is not in small farming. Rescued by a gift of £20 from Allen, he buys a passage home in February 1926, travelling steerage on a French ship the Ville de Strasburg, on which the atmosphere is louche but the food inestimably better. This last diary section, which displays a marked improvement in his descriptive powers, provides some unintended comedy: there is Richard's quaint dismay at being surrounded by 'Froggies, Dagos, Japs and Indians – a rotten crowd' and the odd female passenger who is 'not ... as good as she might be'. He is, he also notes with quiet satisfaction, the only passenger in Third Class who wears a collar and tie.

Comments powered by CComment