- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

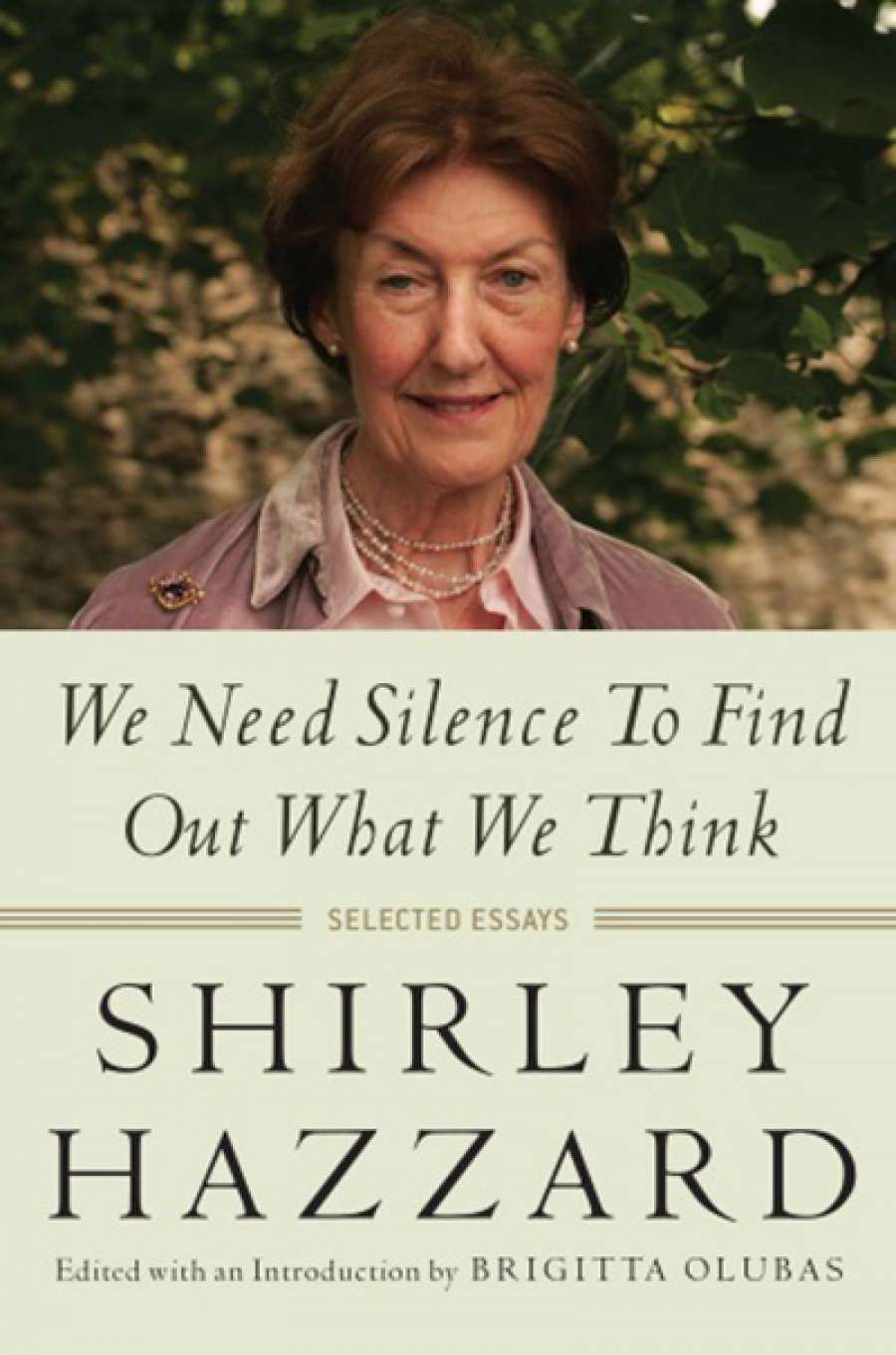

- Custom Article Title: Brian Matthews reviews 'We Need Silence to Find Out What What We Think: Selected Essays' by Shirley Hazzard

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: We Need Silence to Find Out What We Think: Selected Essays

- Book 1 Biblio: Columbia University Press (Footprint), $57.95 hb, 248 pp, 9780231173261

The latter proposes that through art 'we can respond ideally to truth as we cannot in life'. To elaborate, she looks 'outside literature for a moment to draw on the view of a painter, Veronese, who in 1572 was called before the Holy Office to explain why, in a painting of the Last Supper, he had included figures of loiterers, passers-by, people scratching themselves, deformed people ...' Veronese's explanation was, 'I thought these things might happen.'

Hazzard's comment on this simple, apparently guileless suggestion is, 'Despite the convoluted theories expended on the novelist's material, its essence is in those words.' She glosses this rather gnomic proposition by quoting from Auden's poem 'The Novelist', in which he asks that the novelist must 'among the Just / Be just, among the Filthy, filthy too, / And in his own weak person, if he can / Must suffer dull all the wrongs of Man.' It is characteristic of Hazzard's effortlessly referential prose that you find yourself encouraged to add another Auden poem to the argument, the 'Musée des Beaux Arts', in which the poet muses on how 'suffering ... takes place / While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along ... [how] In Breughel's Icarus, for instance: ... everything turns away / Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may / Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry, / But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone / As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green / Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen / Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky, / Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.'

An early copy of Landscape with The Fall of Icarus, Pieter Brueghel the Elder (1526/1530–1569) Royal Museums of Fine Arts, Belgium, via Wikimedia Commons.

An early copy of Landscape with The Fall of Icarus, Pieter Brueghel the Elder (1526/1530–1569) Royal Museums of Fine Arts, Belgium, via Wikimedia Commons.

Like Veronese insisting that the rough and tumble of ordinary life cannot be suspended in deference to some removed and lofty conception of art, Auden likewise is fascinated by life's relentless continuity regardless of human affairs – an observation especially telling for anyone who has suffered profound loss and grief. Hazzard's own referencing, the subtly and beautifully expressed movement of her mind and imagination, prompts further broadening and parallels in the reader.

'The Lonely Word' is centrally concerned with loss, in particular the fourth of Auden's four categories of loss: 'The disappearance of the public realm as the sphere of revelatory personal deeds.' In Hazzard's reading,

... loss, for which in the domain of the arts nothing fundamental has been substituted ... has ever been a constant, in literature as in life. Every civilized person is familiar with Virgil's beautiful invocation of the tears that underlie human transience – tears that Juvenal considered the noblest of human attributes. But the dimensions, character, and acceleration of loss in the contemporary world have created a context of loss amounting to a black hole of the spirit. In the poetry of Montale, loss is a dominant preoccupation – loss of a cat, a shoehorn, a landscape, an attitude, of solitude, of silence. Even his famous simile of the faith that burned like a stubborn log in a fire is something consuming itself – literally to ashes. Beyond this, it can be said that at times the poems of Montale approach a veritable celebration of loss.

The coolly conducted movement in this passage, from the 'idea' of loss to the Virgilian invocation and Juvenal's approbation, are preparations for a sudden but still controlled shift to the quality of modern loss imaged in the thoroughly contemporary reference to the black hole. After that, the pace of this reflection is maintained by the Montale list in which trivialities usher in the massive and consequential, and Hazzard salutes Montale's 'approach to a veritable celebration of loss' in a paragraph that is itself, quietly and subtly, also a celebration of loss. It is only on reflection that one feels the need mildly to note that, thirty-odd years on, the public arena for personal deeds has not disappeared. It is different, remorselessly public in a way that was unimaginable before the arrival of social media, maddening to many in its self-regard, but not inimical to art – not so far as we have seen, anyway.

Shirley Hazzard in 2007 (photograph by Christopher Peterson)The sheer accomplishment of the writing is part of its persuasiveness. Hazard does not insist on the reality of inevitable loss, yet somehow it seems assured. The slightly apocalyptic note here glimmers elsewhere, perhaps most notably in 'Papyrology at Naples', in the concluding paragraph of which she reminds us that 'the concept of written language was not common to all ancient cultures, and trends of our own era indicate how it might die out or revert, as in past ages, to a skill practised by an accomplished few'. In her moving and luminous 'Introduction to Iris Origo's Leopardi: A Study in Solitude', Hazzard's elegant disenchantment with modern city life appears in the guise of a description of Leopardi's prescience: 'He perceived the trend toward volume, velocity, novelty, abstraction; the blunting of insight and intuition, the incapacity for wholeness, the denial of mortality: an infatuation with system that would generate its new chaos.' In a section called 'Public Themes', the United Nations organisation, as she describes it based on her own experience, is the 'new chaos'.

Shirley Hazzard in 2007 (photograph by Christopher Peterson)The sheer accomplishment of the writing is part of its persuasiveness. Hazard does not insist on the reality of inevitable loss, yet somehow it seems assured. The slightly apocalyptic note here glimmers elsewhere, perhaps most notably in 'Papyrology at Naples', in the concluding paragraph of which she reminds us that 'the concept of written language was not common to all ancient cultures, and trends of our own era indicate how it might die out or revert, as in past ages, to a skill practised by an accomplished few'. In her moving and luminous 'Introduction to Iris Origo's Leopardi: A Study in Solitude', Hazzard's elegant disenchantment with modern city life appears in the guise of a description of Leopardi's prescience: 'He perceived the trend toward volume, velocity, novelty, abstraction; the blunting of insight and intuition, the incapacity for wholeness, the denial of mortality: an infatuation with system that would generate its new chaos.' In a section called 'Public Themes', the United Nations organisation, as she describes it based on her own experience, is the 'new chaos'.

Inevitably in such a collection, there is both some repetitiveness – one surprisingly substantial repetition of material from the title essay occurs in 'The Defense of Candor' – and variable depth. Reviews of work by Muriel Spark, Jean Rhys, and Barbara Pym, despite characteristic Hazzardian pointedness and deliberation, seem to be a dutiful nod to inclusiveness, as do the final two pieces, the '2003 National Book Award Acceptance Speech' and especially the 'New York Society Library Discussion, September 2012'. Hazzard scholar, and editor of this collection, Brigitta Olubas, thinks highly of these, but they seem to me to offer not so much a 'dying fall' as a voice trailing off – though perhaps, with nice symmetry, they are fading into that silence we need 'to find out what we think'.

In any case, the concluding pages shine with the brilliant 'Canton More Far' – a portrait of adolescent self-absorption reminiscent of J.D. Salinger's 'De Daumier Smith's Blue Period' – and 'Papyrology at Naples', describing with scholarly affection the Seventeenth International Congress of Papyrology in Naples and noting that, despite a crisis caused by the Getty Museum, papyrologists 'As a body ... seem slow to wrath'. For all the density and range of the title essay and 'The Lonely Word', Hazzard's ironic memoir mode, with its quiet humour and relaxed pace, seems especially to suit her. From We Need Silence to Find Out What We Think, Shirley Hazzard emerges, to paraphrase Olubas, as eloquent, thoughtful, civil, and intellectually generous.

Comments powered by CComment