- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Custom Article Title: Peter Goldsworthy reviews 'Chorale at the Crossing' by Peter Porter

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

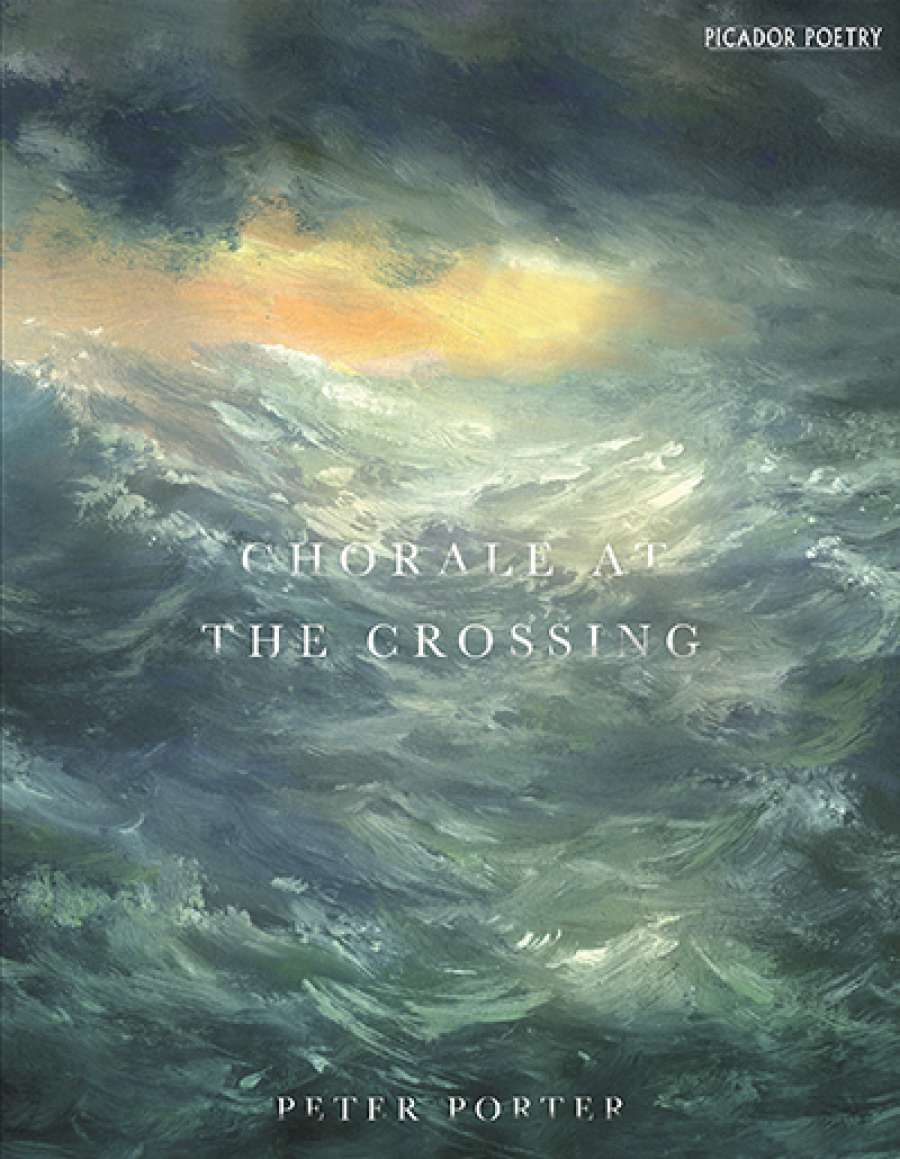

- Book 1 Title: Chorale at the Crossing

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $24.99 pb, 67 pp, 9781509801695

I first came across Porter's work in the wonderful Penguin Modern Poets series when I arrived in Adelaide in 1969, a medical student and seventeen-year old self-styled Angry Young Poet. Given the times, I was more taken with the Beat romance of Penguin Modern Poets 5 (Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, Corso) than with Penguin Modern Poets 2 (Porter, Amis, Moraes) – and more taken with my own world-shaking poems than any of theirs. When, along with a couple of other Angry Young Poets (and an Angry middle-aged Penguin, Max Harris), I miraculously got to read with Ginsberg, and Ferlinghetti two years later, I was so up myself I thought they were the lucky ones.

Peter Porter (photograph by Norman McBeath, courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, Canberra)Some things in the Penguin Porter got through my swollen head, if only because they spoke to adolescent self-absorption: their melancholy, their sexual yearning, their alienation. And that preoccupation with death. As he puts it in one of the 'new' posthumous poems: 'To wonder about the Afterlife / is natural up to Keats's age.'

Peter Porter (photograph by Norman McBeath, courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, Canberra)Some things in the Penguin Porter got through my swollen head, if only because they spoke to adolescent self-absorption: their melancholy, their sexual yearning, their alienation. And that preoccupation with death. As he puts it in one of the 'new' posthumous poems: 'To wonder about the Afterlife / is natural up to Keats's age.'

Oddly, I was less interested in the poems that recalled his Australian childhood than his London poems: the sense of an outsider coming to terms with a metropolis. A black swan of trespass on alien waters? In his heart he felt that way perhaps, but in his head he was already a white swan of Europe. He knew more about European culture than any mere European, and his poems would soon – if not yet - set out to prove it.

Rereading those early poems now (the Penguin selection was taken from his first book, Once Bitten, Twice Bitten [1961], one of the great book titles) the simpler, Australian poems strike me as the more powerful, emotionally – the title poem, for one, and especially 'Ghosts', which summons back his mother (and father). So he was a piebald swan after-all, with a webbed foot trespassing in both hemispheres? It was to be a continuing, and enormously creative tension, in his work.

Porter's poems (mostly) became more cryptic after that first book, both in their allusive, knight's-move connectivity, and in their vast erudition. Those cryptic crosswords once had me looking up things in books, these days it's Google – but it's still an education. His conversations were the same. He was no know-all; just someone who knew everything. You'd want him on your team at a quiz night, although you'd need someone else to cover the sports questions.

Porter is still at it from the grave, in this last book. (But is it the last? Let us hope the immense Porter archive, now transferred to the National Library of Australia, yields further riches.) It is worth checking Google Images before reading 'Dorothea Tanning: Eine Kleine Nachtmusik at the Tate Modern', if only because the title doesn't refer to Mozart, but to Tanning's stunning painting. Google Translate also helps: French, German, and Italian phrases still pepper the poems. Do we need to know that the title of the poem 'Du Holde Kunst' are the opening words of Schubert's famous An die Musik? Porter's more intellectually complex paean to music can probably stand alone, but since the poem also contains the last words from the song – also in German – it helps.

Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (1943) by Dorothea Tanning (courtesy of Tate Collection, London, via www.dorotheatanning.org)

Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (1943) by Dorothea Tanning (courtesy of Tate Collection, London, via www.dorotheatanning.org)

Porter had joked about this in earlier poems – 'the stale erudition / that so enrages your critics', and 'these quotations will keep nobody warm' from 'Ode to Afternoon', a stunning poem from Living in a Calm Country (1975) – and he returns to the theme in this final book:

I'm writing this poem hoping to placate

One of my more forensic critics who

Considers the titles of my poems ridiculous.

So he writes in 'The Singverein of Abstinence', adding, after a stanza beat, the punchline: 'Though perhaps not more so than their contents.'

And 'Singverein'? Both the forensic critic and the forensic fan will probably need to enlist Google. Glee club might be the best, or at least most ironic, translation of that 'German noun, a trope / derived from music' given the poem's sexual lamentations, which include a sideswipe at Ted Hughes – 'The famous black and darting Crow / which pecks its way through every female passage'. Porter never forgave Hughes for his treatment of Assia Wevill (Porter's close friend and Hughes's partner after Sylvia Plath), who killed herself and their daughter in 1969.

Porter's first wife, Jannice, took her own life in 1974. After a long afternoon (and evening) lunch at one of his favourite watering holes in London, he once intimated that he felt Sylvia Plath's and Wevill's suicides had perhaps made it less difficult for Jannice to make the same choice. How much grief can one lifetime accommodate? This terrible loss is at the heart of his magnificent collection The Cost of Seriousness (1978) and its justly celebrated pieces such as 'The Delegate' and 'An Exequy'. The key poem for me in that collection is 'A Lecture by my Books', which prefigures his move into an even more oblique, allusive poetry from that point on, not so much because it is oblique itself, in its displacement of the poet's own suicidal impulses, as for the profound struggle with the limits of language which it represents.

Porter returns to this in the title poem of Chorale at the Crossing, wrestling with the inadequacy – indeed, irrelevance – of poetry to grief:

I have come no closer to my goal

of doing without words, that

pain may be notated in some real way.

Many of these last poems refract earlier ones, and can be read usefully in their light. 'Your Considerate Stone' is crammed full of, well, stones – tombstones, dolmens, Easter Island statues, Grabmals (look it up; Porter can't resist a German obscurity) and even gallstones: 'And if your heart's / a hardened gallstone, it might claim / consideration of its species' quality / the hardest of hard things inherited.' 'The world your stone, the word as stone' speaks to one of his most unforgettable poems: 'What I Have Written I Have Written' and its 'little stone of unhappiness / which I keep with me'.

'The past is my present tense' Porter writes in 'The Castaway is Washed Ashore', another poem in which he returns to the deaths of his mother and his first wife, using the simple metaphor of the loss of both 'ships' in which he travelled, and – a recurrent theme – the construction of those various consolations that helped him survive.

Love was chief among them. Love of his children, grandchildren, friends; love for his second wife, Christine. The least indirect of these last works is addressed to her, another safe ship: 'I have caught a late boat and see you / against the rail.' This is a beautiful love poem. Its recipient has answered it, in a way, in a perceptive postscript to the book, talking of her late husband's continuing struggle 'with the idea of home', and the sense 'of not quite belonging.' Or, as he puts it himself, in another poem, and a different context:

To be alone is every person's gift,

Though crying in the night is a reminder

That Happy Valleys are Repression's Rift.

Christine Porter, a psychoanalyst, might echo that. She singles out the final poem in the book, 'Hermit Crab', and its simple, central metaphor. 'I have no new shell to retreat to' the poem begins, as our castaway-cum-soft-shell-crab seeks the shelter of shells not ships:

Without a home, one made of current comforts

And loving faces, forgetting

Becomes impossible.

The poet's mother was his first comfort, the 'mother-of-pearl' of his first shell, as Christine suggests, but another was always the 'glorious nacre' of human knowledge: music, painting, science, history. And poetry, of course, his among it. Is there extra comfort in the notion that our art at least outlives us? Robert Browning hoped so, but wasn't too sure. Like Browning, Porter liked to inhabit other minds in his poems; many are acts of ventriloquism. His witty update of 'A Toccatina of Galuppi's' is done in the same octametric rhyming tercets as Browning's poem of the same name, but is even more pessimistic:

What hangs in minor keys and major lingers in the mind like lead.

'Those suspensions, those solutions – must we die?' and then we're dead.

In the Ca' Rezzonico, one Robert Browning climbs to bed.

The Ca'Rezzonico? Time for Google Maps? Maybe not; equally often we can go with the context of the poem. I somehow managed to learn more from my acquaintanceship with Porter than with Ginsberg, but could have done better. Certainly, I wish I had talked less and listened more. Luckily, his voice goes on teaching us from the other side of the Crossing. Or to mix his own metaphors, the voice of the hermit crab can still be heard whenever we hold one his books to our ears.

Here's one to finish. Peter Porter was always generous to visitors in London, numerous Australian poets among them. Some are farewelled here with amusing clerihews, including the editor of this magazine, but since I started this review with death I might end with a clerihew about sex:

Havelock Ellis

said, 'Listen, Fellers

sex can derail yer

even in Australia.'

Up to Keats's age, that's just about all ye know on earth – if not all ye need to know. Peter Porter can help out with the rest.

Comments powered by CComment