- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

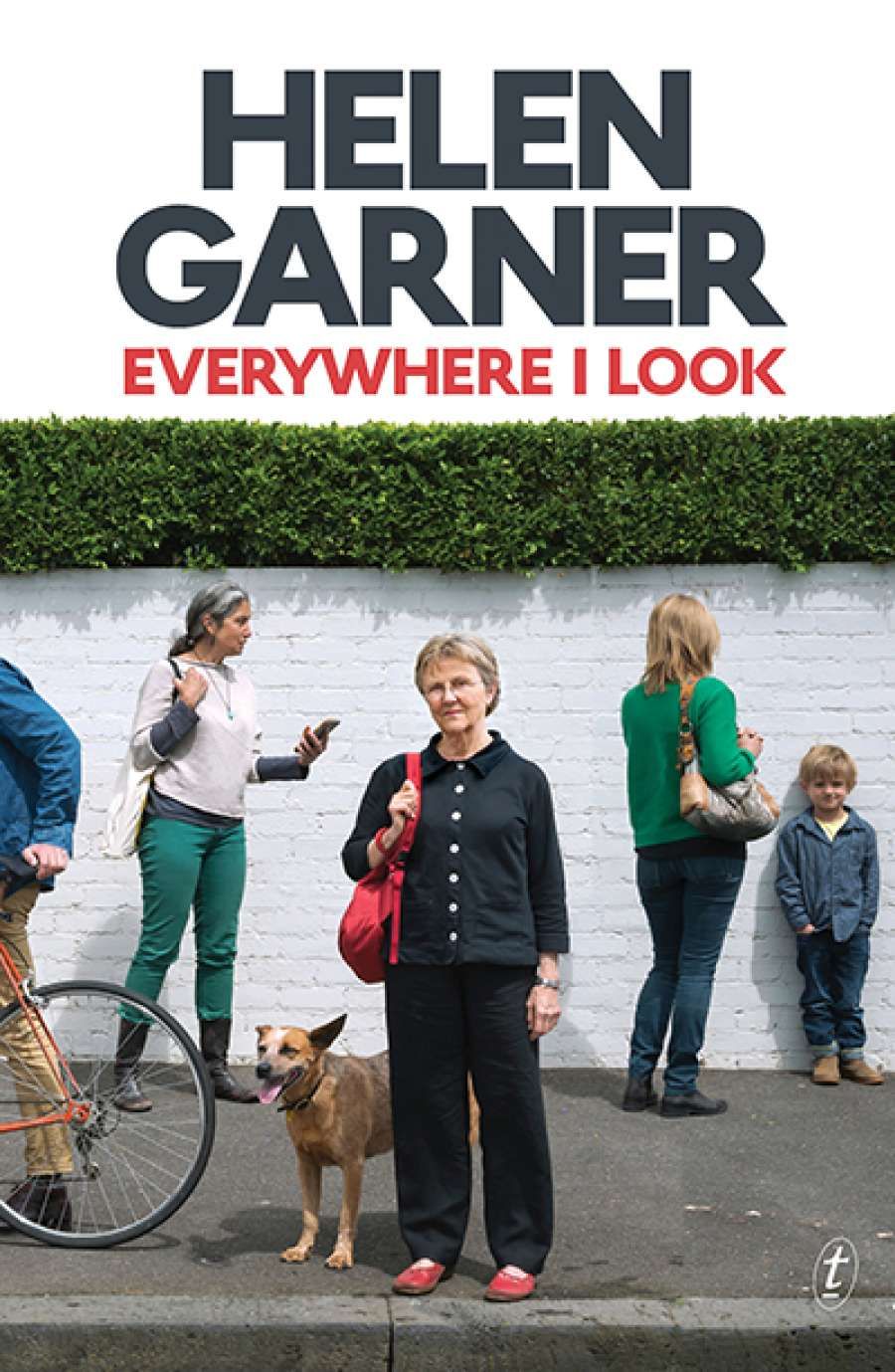

- Custom Article Title: Jill Jones reviews 'Everywhere I Look' by Helen Garner

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Everywhere I Look

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing $29.99 pb, 229 pp, 9781925355369

While Everywhere I Look may seem like a loose assembly of reviews, diaristic fragments, essays, short articles published over many years, it feels as though it has been selected and ordered carefully. This almost indexical quality, and its curated sense of a series of engagements with place, people, and objects, presents a way of writing autobiography which seems unintentional, yet coherent all the same. While some of the essays embrace the fragmentary as a device, particularly in the third section on the writer's life, the pieces end up conversing back and forth through the book, and there are a number of recurring characters, friends and family members, which build this casual, unified sense.

Garner has always been interested in the permutations of love and relationship, and the self within in civic and community life. Much of her writing, especially the non-fiction, is an examination of why these things are so difficult but also why they matter. Thus, Garner in this book, as in many of her previous ones, is fairly tough on many people – strangers and friends, but also herself.

At times, any reader may find herself puzzled by Garner's apparent contradictions of grace and wrath, or disagree with her almost offhand cruelty. Perhaps this is an Australian trait, or what she terms, in a different context in this book, her 'puritanical savagery'? For instance, she doesn't pull off the passing comment that a gay friend in late 1970s Paris was 'busily catching AIDS', simply because he was always out in bars or cruising. It's flippant and offensive.

Still, the ethical controversies her work can engender have been canvassed many times. At this point in her career, most readers will be familiar with, and have their opinions about, Garner's heightened form of subjectivity, and sometimes less than judicious framing of people, motives, and events.

In this collection, the thing that strikes me most forcefully is the rendering of the bodied self in the everyday, such as the touching physicality of her relationships with her grandchildren and the essential requirements of a kitchen table. But I don't want to infer that this book is simply about the quotidian. It encompasses all the great themes – love, death, the weather – through various measures and trajectories, including relationships with other writers and a revisiting of the law and crime.

The first part of the book, 'White Paint and Calico', sets the scene for the book, as a reassessment of suburbia; in a sense, a confessional. She writes: 'I am ashamed now of my bohemian contempt for the suburbs of my childhood.' She writes of her new neighbourhood, where neighbours act together against officious policing; they look out for each other. Central to this are important objects and places, including that kitchen table, the backyard, all evoking a certain kind of Australian existence, a kind of practical, communal approach to daily living.

The book also raises some interesting questions about art-making, especially writing. Garner's prose may appear to be plain-spoken, crisp, approachable. She certainly has a sublime knack for description which admits a tangible sense of place, so you know what the table, the backyard, the city street looks like and what the weather is at the time. You are as much there as Garner appears to be. But that is the point, it is about appearance. While she may criticise Barbara Baynton in one review ('You can feel her sometimes putting on side, striking writerly poses, indulging in misty poeticisms'), you may ask, 'But isn't all writing artifice?' The plain speaking embrace of the quotidian is no less an aesthetic than the European high style she feels uncomfortable with when talking with her writer friend Jacob Rosenberg, who leant on 'philosophical generalisation, ... who worshipped at European cultural shrines'.

Helen GarnerGarner's writing moves easily from description or narrative right into the metaphorical. Take this sentence: 'The little round table floated on its expanse of floor like an autumn leaf on a lake.' This is mostly figurative writing; it could almost be turned into two or three lines of a poem.

Helen GarnerGarner's writing moves easily from description or narrative right into the metaphorical. Take this sentence: 'The little round table floated on its expanse of floor like an autumn leaf on a lake.' This is mostly figurative writing; it could almost be turned into two or three lines of a poem.

In another article, a review of the film United 93 by Paul Greengrass, she remarks: 'I have a rule of thumb for judging the value of a piece of art. Does it give me energy, or take energy away?' This could also sum up what she offers readers. If Garner's primary context is everyday life, she gives this energy by combining clarity with the, dare I say it, lyrical. You don't have to agree with her opinions or judgements, but you are in a field of energy, of absolute engagement. In this vital way, Helen Garner in this latest work adds to our thinking about writing, how it is done, and for what purpose.

Comments powered by CComment