- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Michael Morley reviews 'Nicholas Nabokov: A Life in Freedom and Music' by Vincent Giroud

- Book 1 Title: Nicolas Nabokov: A Life in Freedom and Music

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, $47.95 hb, 577 pp, 9780199399895

But such an exhaustive (and exhausting) approach does raise a number of methodological questions relating both to the author's procedure and his sense of priorities. At more than 560 pages of eye-watering close type, this study is longer than, for example, Elizabeth Kendall's dual biography of Balanchine and Lidia Ivanova, which clocks in at a mere 250; competes with Paul Kildea's more readable and informative biography of Benjamin Britten (just over 600 pages without index); and exceeds both Richard Buckle's and Bernard Taper's Balanchine biographies by almost 100 pages.

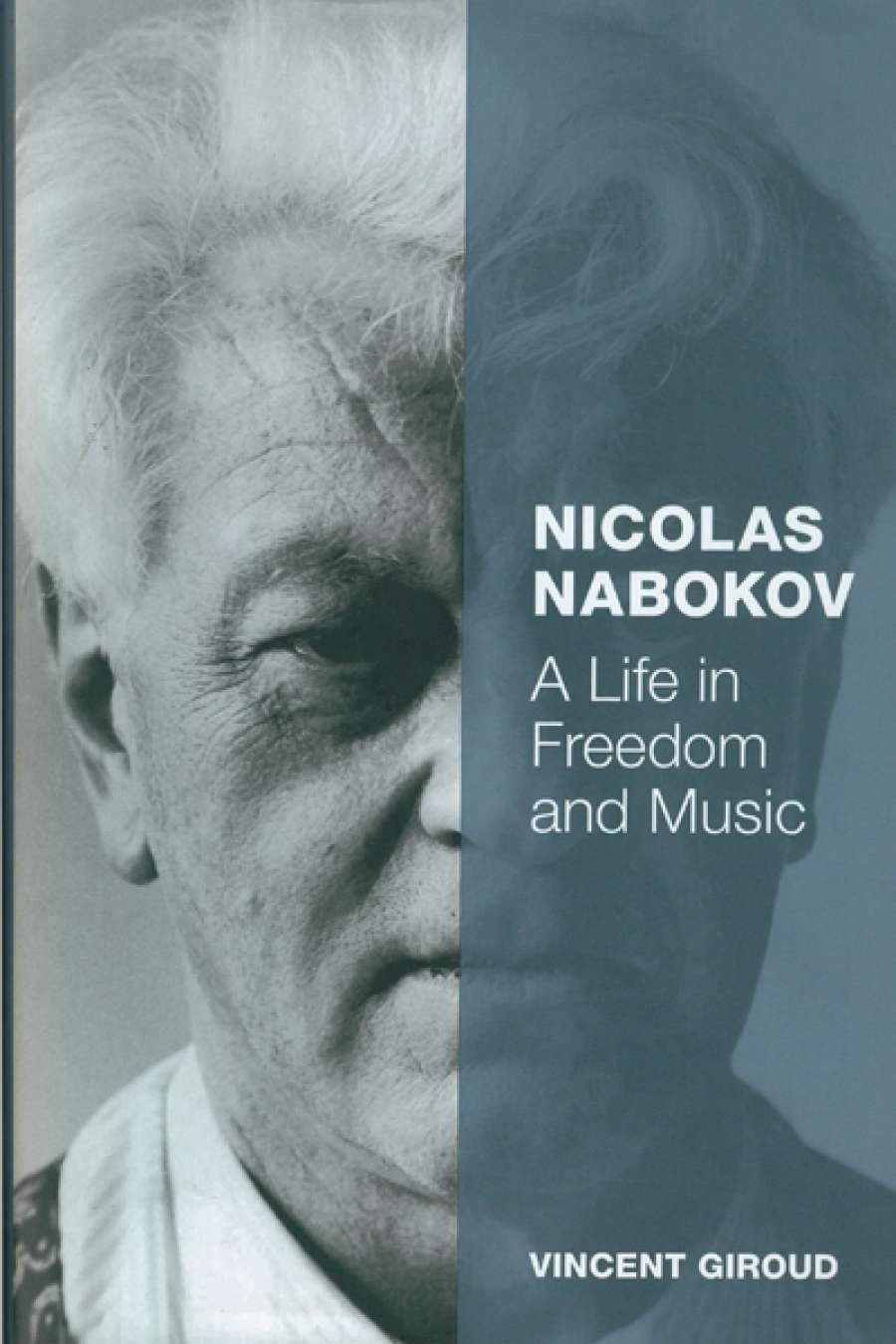

To be sure: Nabokov's roles as cultural adviser, music academic, critic, commentator and composer deserve attention and an attempt to place him in a contemporary and wider context. But when two not untypical pages have him, in the spring of 1940, enjoying the hospitality of Francis Biddle, the recently appointed US solicitor general and his wife 'the poet Katherine Garrison Chapin ... the sister of Marguerite Caetani, whom Nabokov knew from his years in Paris'; being 'charmed' first by 'quiet and tidy Annapolis' and immediately thereafter by Scott Buchanan, who 'had majored in Greek and mathematics at Amherst College and subsequently read philosophy as a Rhodes Scholar at Balliol College Oxford' before teaching at the University of Virginia, using ideas formed 'in association with his fellow philosophers Mortimer Adler and Richard McKeon'; and finally meeting with a figure who 'was determining in his future postwar career' – a young American diplomat with, in Nabokov's own words, a 'noble face with all its parts in perfect proportion to each other, well cut, or rather stonehewn, the way I imagined early Roman Republican consuls', one can perhaps be pardoned for momentarily laying the book aside and humming the odd bar from 'Widecombe Fair'. Nicolas Nabokov with his cousin Vladimir, 1975 (photograph by Dominique Nabokov)

Nicolas Nabokov with his cousin Vladimir, 1975 (photograph by Dominique Nabokov)

If Nabokov had one exceptional talent it surely had to be for what is now called networking: the term could have replaced Dmitrievich as his middle name. But Giroud surely does his subject a major disservice in being seemingly unable to capture the one quality to which so many of the other major figures in these pages constantly refer – his charm. This was not just empty charm, but charm allied to a whole range of interests: dance – Russian, European and American; the visual arts; literature; the theatre; and above all, music.

The major problem with what will undoubtedly remain the major sourcework for Nabokov aficionados for years to come is that, throughout its length, it is not just a case of the reader having difficulty in seeing the wood for the trees, but of frequently not even making these out amid the shrubbery, herbaceous beds, rock gardens, and overgrown orchards that populate the work's pages.

Tougher guidance at Oxford University Press would have given these pages greater shape and flair: too often the reader has the impression that facts, names, locations, and menus have been thrown at the pages in the hope that they will both stick and reconfigure themselves as argument or coherent portrait.

That said, for the patient reader, there are chapters in the book that do spell out Nabokov's important role in actually making things happen. The figure that Stravinsky nicknamed 'culture generalissimo' was responsible, inter alia, for a major festival in Paris in 1952 devoted to Masterpieces of the Twentieth Century and encompassing a wide range of music, dance, theatre, literature, and the visual arts. Occupying centre stage were works by Berg, Britten, Stravinsky, Copland, Thomson, Ives, Schoenberg, and Boulez; while the art exhibitions were also intended, like the musical side of the festival, 'to make the point that ... [they], in the twentieth century, had flourished especially when benefiting from a climate of cultural freedom.'

It is at this point that the major issue in which Nabokov was to find himself embroiled has to be addressed: his role in the Congress for Cultural Freedom and its now established links with the CIA. Giroud is emphatic that Nabokov was not aware of the connection or the channelling of funds: other critics (to whom he does, in fairness, refer) were and are, not so certain. If, as Nabokov himself stated at the time, he found the central figure of Melvin Lasky 'an American equivalent of the apparatchik', one is surely justified in wondering whether he was simply turning a half closed eye or was genuinely unaware of Lasky's connections.

Alex Ross, for one, is unconvinced, pointing out in The Rest Is Noise (2012) that funding for the event 'was said to have come from the Fairfield Foundation ... In fact, Fairfield was a front, its financing arranged entirely by the CIA.' (Ross is also rather more critical than Giroud of the Festival itself, characterising it as 'elaborate, expensive and incoherent' and citing Boulez, who later criticised Nabokov for creating 'a folklore of mediocrity', while sarcastically recommending that a future festival 'celebrate the twentieth-century condom')

And yet, one has to admire someone who can suggest to Stravinsky that, for his 1964 Berlin Festival, he might 'consider making an orchestral arrangement or rather a transformation for voice and orchestra (in the way you did so beautifully with Bach) for two, three, or four Negro Spirituals'; who was a strong and persistent advocate of what he saw as unjustly neglected works (such as Les Noces and The Flood or Darius Milhaud's Oresteia trilogy); and whose Berlin Festival is remembered by cultural historians as 'the most exciting international gathering of black artists in memory.'

For a sense of Nabokov's own personality, as well as of the warmth and esteem in which he was held by his fellow-musicians, the interested observer is better served by the Canadian television footage of a fifteen-minute conversation with Stravinsky from 1963 (available on YouTube) in which the long-time friends and sparring partners demonstrate bonhomie and wit in three languages, together with the qualities singled out by Isaiah Berlin.

Comments powered by CComment