- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Food

- Custom Article Title: Christopher Menz reviews 'Food in Art: From Prehistory to the Renaissance' by Gillian Riley

- Book 1 Title: The Edible Monument: The Art of Food for Festivals book

- Book 1 Biblio: Getty Research Institute, $62 hb, 190 pp, 9781606064542

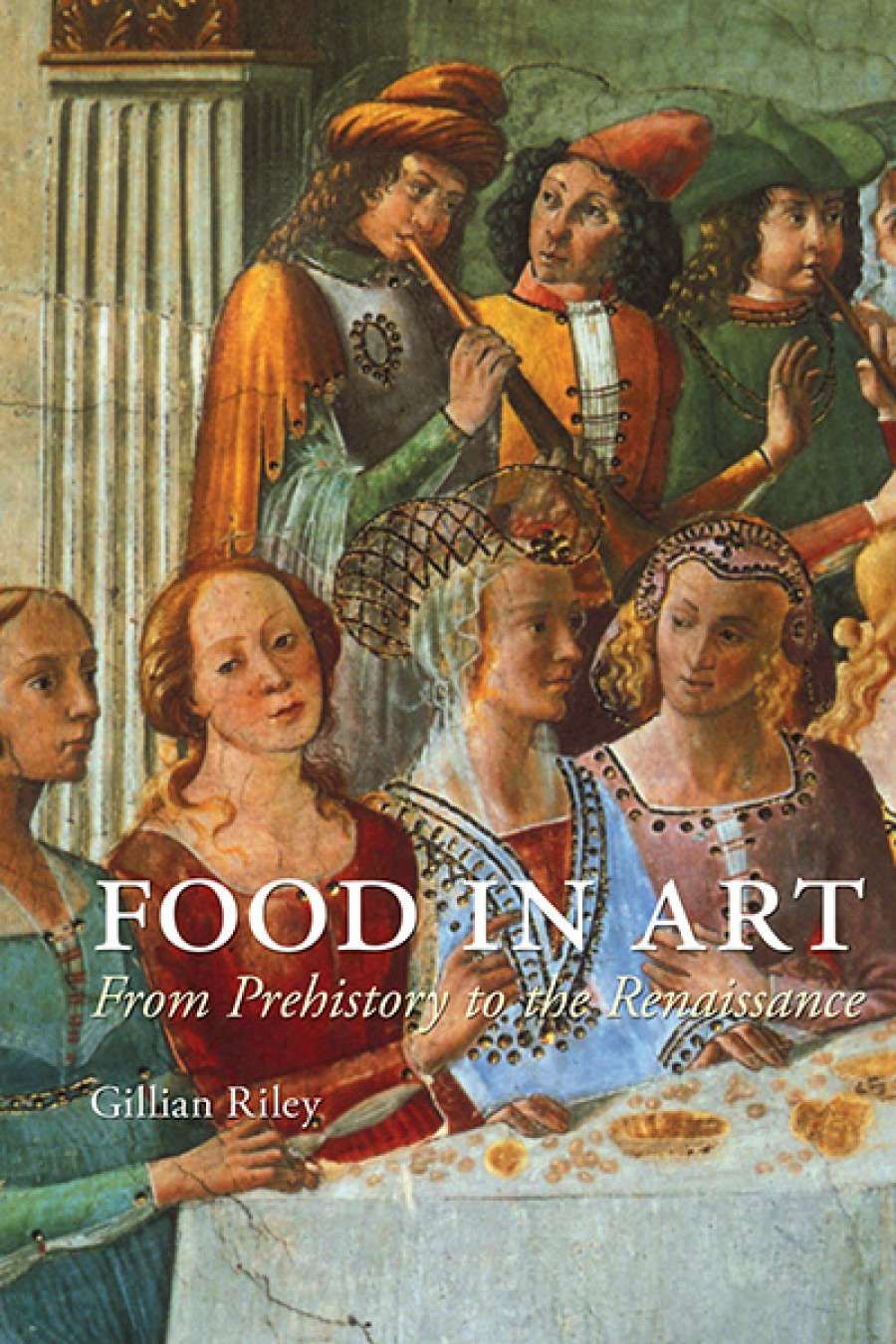

- Book 2 Title: Food in Art: From Prehistory to the Renaissance

- Book 2 Biblio: Reaktion Books, $69.99 hb, 319 pp, 9781780233628

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

From the Renaissance to the eighteenth century, the most important court and civic rituals involved elaborate ceremonies, often centred on food presented in fantastical ways. Not only was the food at banquets edible; so was much of the elaborate artistic table decorations. This art is almost entirely lost to us, but it is worth remembering that many of the small eighteenth-century porcelain figurines that are now collectors' items were themselves originally produced as table decorations. They in turn derived from decorative table sculptures made of sugar, known in Italian as trionfi.

One of the most remarkable Italian historical food events was the Cuccagna festival, which relates to the Land of Cockaigne, a mythical place of easy labour and endless food. They were popular in Italy from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, and were frequently associated with Carnival. Highly decorative and mostly edible monuments in the form of arches, battle scenes, and tableaux were set up in public spaces in the city. After viewing by courtiers and at the right signal, the populace 'sacked' the monuments and took away what they could eat.

Luilekkerland (The Land of Cockaigne)by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1567) (Alte Pinakothek via Wikimedia Commons)

Luilekkerland (The Land of Cockaigne)by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1567) (Alte Pinakothek via Wikimedia Commons)

Nowadays, we are more familiar with the idea of the grand ceremonial banquet to celebrate important events. Several of the more significant festivals were recorded and illustrated in sumptuous publications. Not surprisingly, some of the grandest occurred in Louis XIV's gardens at Versailles. The festival books by André Félibien document and illustrate these theatrical events that were designed to delight all the senses. Lasting several days, these complex rituals must have been exhausting. One of the more subdued sections of the 1668 festival, a celebration the Treaty of Aix-la Chapelle, is described by Marcia Reed: 'Each table had a different food theme: a mountain with cavern in which guests saw all types of frozen meats; a palace façade constructed of marzipan and sugar paste; pyramids coated in cuttlefish confections; and one with innumerable vases full of liqueurs.'

Marcia Reed, the editor and chief contributor, is assisted by others: Joseph Imorde contributes a fascinating essay entitled 'Edible Prestige'; Charissa Bremer-David explores eighteenth-century French serving dishes; and the pre-eminent food historian, Anne Willan, looks in more detail at the food, cooks, and presentation. The Edible Monument is published to the Getty's normal superb standards, and is beautifully illustrated.

In her volume Food in Art: From Prehistory to the Renaissance (Reaktion Books, $69.99 hb, 319 pp, 9781780233628), Gillian Riley goes directly to visual sources, using images to show food from prehistory to the Renaissance, an ambitious span. She covers ancient Middle East and Mediterranean civilisations in some detail before embarking on the richer resources of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Riley, eschewing literal readings, is sensibly cautious in interpreting images and provides thoughtful practical and symbolic interpretations. She also brings her extensive knowledge of cookery to the task, having published extensively on Italian food. Riley exploits a rich variety of images, many not well known, to illustrate the narrative. There is much more to enjoy than the predictable still lives and kitchen scenes: in addition to these are marvellous images from ancient Egypt and Rome and fascinating ones from the medieval early Renaissance periods.

Old Woman Frying Eggs by Diego Velázquez (1618) (Scottish National Gallery, via Wikimedia Commons)Given the necessary focus on works selected from European and North American collections, it is refreshing to see one work from an Australian institution: Giuseppe Recco and Luca Giordano's vast The riches of the rea (1684) from the Art Gallery of South Australia. Visitors to the Art Gallery of New South Wales over summer also had the opportunity to enjoy Diego Velázquez's superb painting, Old woman frying eggs (c.1618), on loan from the National Gallery of Scotland. It is to be hoped the second edition will name the collections in the picture captions.

Old Woman Frying Eggs by Diego Velázquez (1618) (Scottish National Gallery, via Wikimedia Commons)Given the necessary focus on works selected from European and North American collections, it is refreshing to see one work from an Australian institution: Giuseppe Recco and Luca Giordano's vast The riches of the rea (1684) from the Art Gallery of South Australia. Visitors to the Art Gallery of New South Wales over summer also had the opportunity to enjoy Diego Velázquez's superb painting, Old woman frying eggs (c.1618), on loan from the National Gallery of Scotland. It is to be hoped the second edition will name the collections in the picture captions.

Food in Art covers a great deal of territory and draws many strands together in an engaging and entertaining manner. Not all the dishes illustrated are edible: the illustration of the medieval credenza (buffet) is in a painting entitled Banquet of Herod, in which the central feature is a kneeling Salome presenting John the Baptist's head on a platter.

Comments powered by CComment