- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: True Crime

- Custom Article Title: David Nichols reviews 'Pentridge: Behind the Bluestone Walls' by Don Osborne

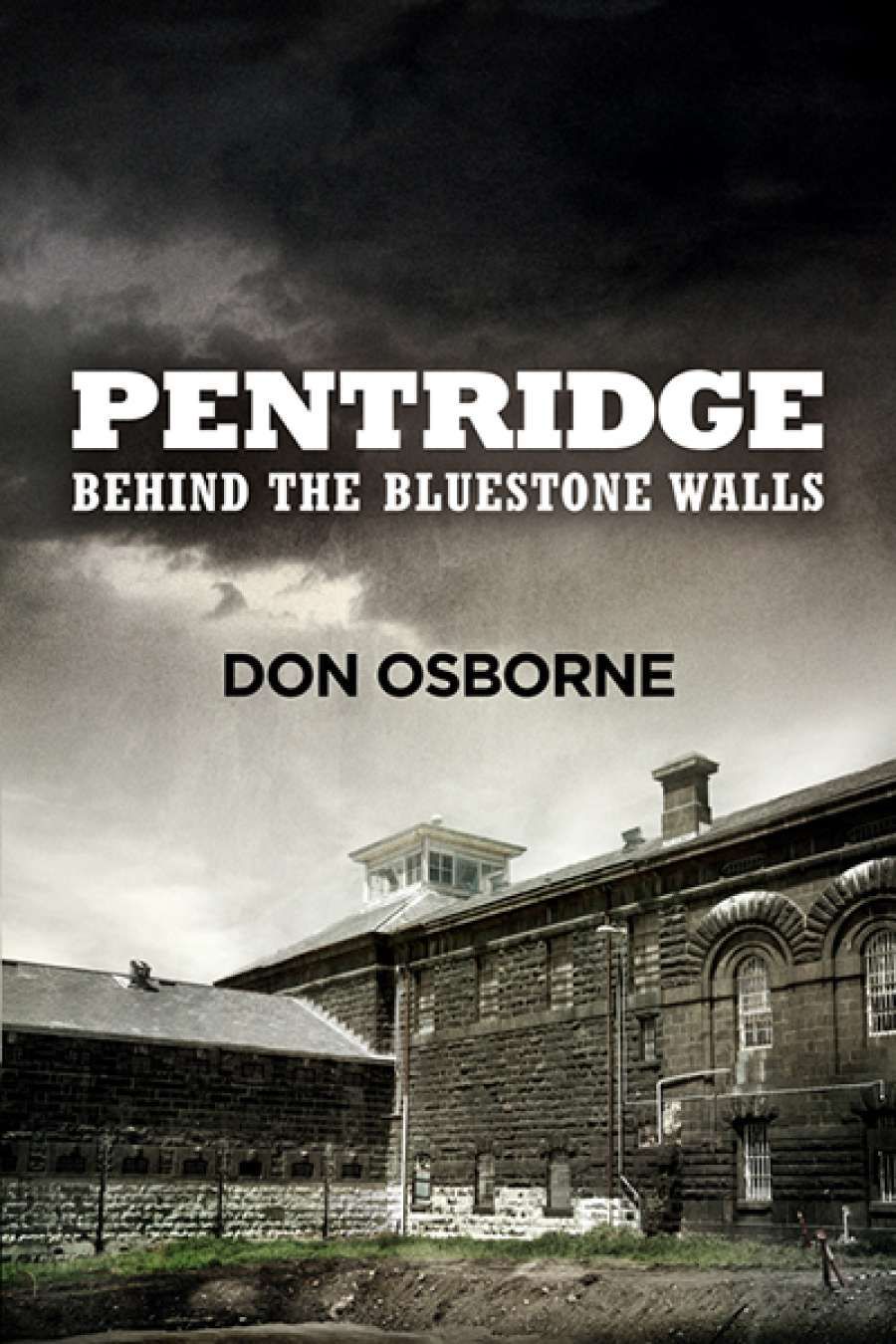

- Book 1 Title: Pentridge: Behind the Bluestone Walls

- Book 1 Biblio: Echo Publishing, $32.95 pb, 336 pp, 9781760068547

While it does contain insights, it has to be said that Osborne's book is uneven. He was an education officer at Pentridge, and the chapters in which he details his experience and observations of the prison, its staff and inmates, are the most rewarding. The relationships and dynamics between 'officers' and prisoners are what he is most qualified to talk about, yet having made some very starkly illustrative comments on these matters, he turns from his own recollections of his time at Pentridge, which occupy only about a sixth of the book. Much of the remainder of Pentridge features potted biographies of the biggest 'name' criminals who came through the prison's population. Some are organised crime figures – contract killers and the like – but most are unbalanced and sociopathic men, often incarcerated for horrific murders. Osborne ticks these criminals off one by one, but does not discuss in any significant detail their subsequent lives at Pentridge.

Much of the material herein comes close to common knowledge – the discussion, for instance, of the Ronald Ryan case in the 1960s – and can surely be easily located online, should one be of a mind to sniff it out, or in other books. Osborne's sources are largely secondary. He is even content – curiously for someone with a keen mind – to regard a novel about the 'brownout' murderer Leonski as valid source material.

![]() Pentridge Prison Panopticon Ruin 2015 (photograph by Michael J Fromholtz, via Wikimedia Commons)

Pentridge Prison Panopticon Ruin 2015 (photograph by Michael J Fromholtz, via Wikimedia Commons)

Elsewhere, we are presented with approaches that do not enhance the material (let alone the lives of trauma and despair). Osborne, in general a careful writer, draws no direct connection between his subjects' troubled domestic environments and their offences, though the implications are plain. Other portions of the book feature further non sequiturs. That murderer Robert Tait 'engaged in homosexual activities' as a young marine is presented with no framing or discussion, leading the reader to wonder at implied connections between this essentially unremarkable detail, Tait's transvestism, and his perpetration of domestic violence on his (unnamed) wife.

Peter Doyle's book City of Shadows (2005) is a haunting collection of police photographs less for anything grisly (though it has that) and more for the ad hoc nature of the homes and streets that were as unprepared for the unblinking eye of a photographer as they were for anyone's death. Similarly, Osborne's Pentridge tales are detached pen-portraits of slices of lives gone wrong: disturbed men blundering through the landscape, uncontrollable, their offences always appearing, in hindsight, a foregone conclusion given the psychological damage so many of them suffered in early life. Whether we learn anything from going over this ground (again) is unclear; Osborne's insight is only fleeting and, in the biographical factoid section of his book, almost non-existent.

Don Osborne

Don Osborne

Much of the Pentridge site today is a high-density housing development of large-windowed apartment blocks. Meandering leafy streets perplex anyone trying to track the old site beneath the new estate – which was, of course, the whole idea – although much of the high bluestone wall is still in place. The remnant prison buildings themselves are a wicked heritage problem; like the mental asylums of mid-nineteenth-century Victoria, they are too iconic to demolish, but aside from the redoubtable Willsmere, now high-end residential apartments, hard to do anything else with.

There is a similarity between this book and Pentridge Village. Pentridge is still visible as you drive north along Sydney Road through Coburg (the suburb changed its name in 1870 to escape the stigma of the prison) but it is a cipher; only the empathic experience a cold shiver at the sight. Osborne's book is also an entertaining trip down a blood-splattered memory lane, where the name of the prison is a cipher catch-all for a cavalcade of associated sordid concepts. The fascination, such as it is, still feels a little dirty.

Comments powered by CComment