- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Russian History

- Custom Article Title: Mark Edele reviews 'On Stalin's Team' by Sheila Fitzpatrick

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

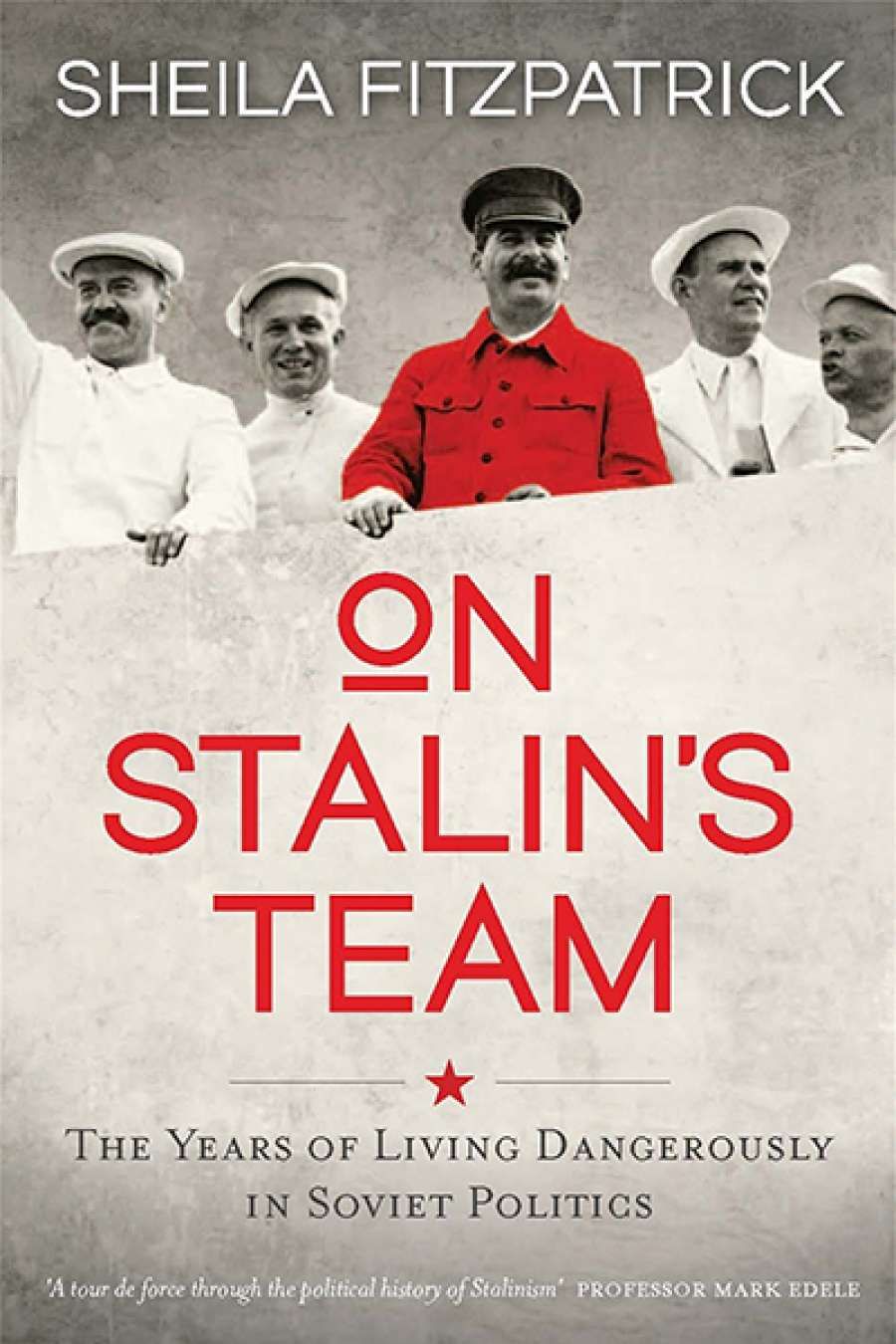

- Book 1 Title: On Stalin’s Team: The Years of Living Dangerously in Soviet Politics

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $59.99 hb, 375 pp, 9780522868913

Fitzpatrick's choice of topic might surprise, given her reputation as an exponent of 'history from below.' Her oeuvre brought social history analysis to the study of the Soviet Union. This approach was never confined to one particular subject. It could be focused on supporters of the regime as well as on its victims. Indeed, her first monograph – The Commissariat of Enlightenement (1970) – can be classified as political history. Her landmark Education and Social Mobility in the Soviet Union (1979) also intersected social with political history. It pointed out that an entire cohort of Soviet citizens had benefited from policies designed to replace the old 'bourgeois specialists' with new cadres from the working class, who became committed clients of Stalinism. The theme of loyalty to the leader re-emerges in On Stalin's Team, this time from the vantage point of his inner circle. It is not likely to trigger the same kind of outrage as in the 1970s and 1980s, when Martin Malia or Richard Pipes read it as 'revisionist' advocacy for Stalinism, an attempt to legitimise a totalitarian regime.

Fitzpatrick baffled such critics with her bestselling The Russian Revolution (1982), which integrated Stalin's revolution from above (1928–32), and from the 1994 second edition even the Great Terror (1937–38), thereby opposing Marxist scholars, who separated the Leninist revolution from its Stalinist offspring. This was indeed an 'unrevisionist' account, as a noticeably confused Pipes wrote in a 1993 piece attempting to discredit social history yet again for the already convinced readers of The National Interest. Then, in her ironically named 1994 monograph Stalin's Peasants, Fitzpatrick demonstrated that hers was a neutral method, which could study the victims of the regime as much as its beneficiaries.

Stalin, Voroshilov, Mikoyan, and Molotov on the Lenin Mausoleum on the eighteenth anniversary of the Revolution, 1935 (RIA Novosti)

Stalin, Voroshilov, Mikoyan, and Molotov on the Lenin Mausoleum on the eighteenth anniversary of the Revolution, 1935 (RIA Novosti)

On Stalin's Team, then, is both a return to an earlier interest in those who supported Stalin and a continuation of her unrevisionist revisionism. It also answers a new set of critics. By the 1990s, scholars inspired by new cultural history and the linguistic turn began to focus on Fitzpatrick's old topic of loyalty, but grounded not in social mobility but in ideas. Self-indoctrination led to regime support, they argued, not the self-interest of social climbers, as in Fitzpatrick's work. A parallel criticism decried the fact that Fitzpatrick's Everyday Stalinism (1999) focused on ordinary city folk and their struggles to survive. Did the political élite not also have an everyday life? Did Fitzpatrick again 'leave the politics out'?

Kirov, Stalin, Kuibyshev, Ordzhonikidze in front row, with Kaganovich, Kalinin, and Mikoyan (obscured) behind, 1934 (RGASPI)What better way to counter such critics than to write the history of everyday life of the dictator's political associates. Unrevisionist as usual, Fitzpatrick agrees with much of the established historiography. There is no question that Stalin and his men were animated by communist ideology. There is no argument against the fact that Stalin's revolution of the early 1930s and the Great Terror later in the decade emanated from above. Stalin started the terror and ended it.

Kirov, Stalin, Kuibyshev, Ordzhonikidze in front row, with Kaganovich, Kalinin, and Mikoyan (obscured) behind, 1934 (RGASPI)What better way to counter such critics than to write the history of everyday life of the dictator's political associates. Unrevisionist as usual, Fitzpatrick agrees with much of the established historiography. There is no question that Stalin and his men were animated by communist ideology. There is no argument against the fact that Stalin's revolution of the early 1930s and the Great Terror later in the decade emanated from above. Stalin started the terror and ended it.

Elsewhere, the book pushes perceived wisdom in new directions. The most original of these interpretations concerns what happened to the team in the final years of the dictator's life and after his death. Fitzpatrick builds here on recent research on the late Stalin and early post-Stalin years. Much of this literature has traced the origins of what we usually see as 'Khrushchev's reforms' back to the 1940s and early 1950s, when inside the Soviet system a variety of plans for radical change were hatched but shelved because the dictator was not interested. Fitzpatrick shows that even Stalin's team shared the view that the system needed reform. In particular, his associates recognised that the sprawling Gulag was both expensive and socially destructive; they wanted to dial back the level of terror. They were appalled by the anti-Semitic campaign that Stalin had unleashed in what looked like the beginnings of a new purge of the political leadership. This consensus explains why, after Stalin's death in 1953, reforms were instituted so quickly and so comprehensively.

This point is crucial for a wider interpretation of the role of Stalinism in the longer sweep of Soviet and post-Soviet history: The team indeed survived Stalin, and it broke apart only when Khrushchev, in 1957, once again arrogated the position of undisputed leader. Historians, political scientists, and pundits often speculate that authoritarian one-man-leadership is the natural state of affairs in 'Russia': a clear line from the Romanovs to Putin. Periods of collective leadership are aberrations, moments when the system got destabilised before it returned to its equilibrium. Fitzpatrick turns this reading on its head. As far as the Soviet Union is concerned, one can legitimately argue the reverse: clearly, in the mind of many of the participants, it was collective leadership that was normal, not dictatorship. The periods where one man ruled without much consultation of and even in opposition to the wider circle of leaders are episodes; more often, collective leadership prevailed.

On Stalin's Team, then, has a lot to offer to historians as well as the general public. It can be read as a stand-alone introduction to the political history of the Soviet Union in the crucial years between the 1920s and the 1950s. In either case, this exhaustively researched and engagingly written study will take them into a strange and frightening world: the world of Stalin's team, poised to 'live dangerously in Soviet politics.'

Comments powered by CComment