- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthology

- Custom Article Title: David McCooey reviews 'Falling and Flying' edited by Judith Beveridge and Susan Ogle

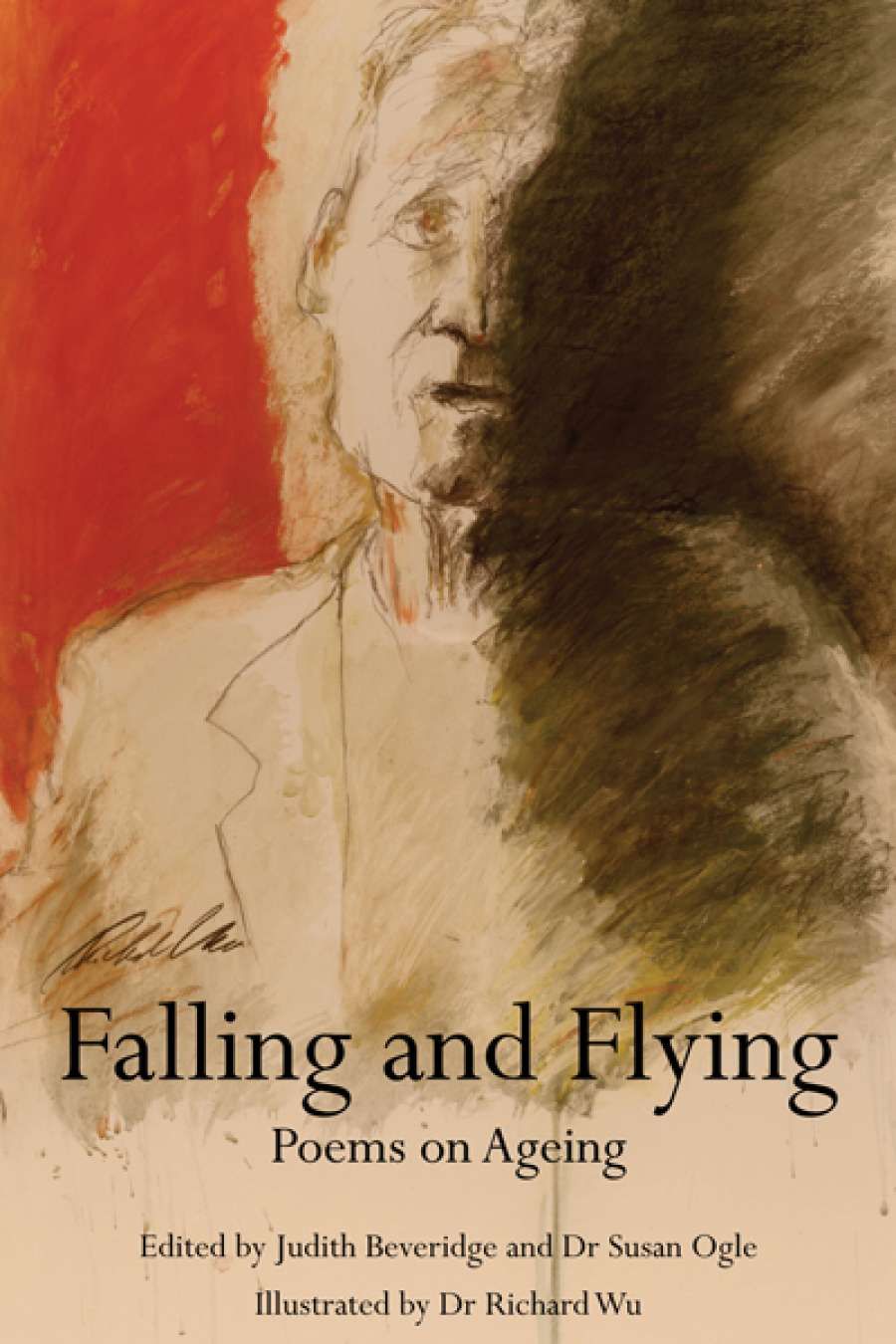

- Book 1 Title: Falling and Flying

- Book 1 Subtitle: Poems on Ageing

- Book 1 Biblio: Brandl & Schlesinger, $29.95, 206 pp, 9781921556876

This is an ambitious but laudable goal. The idea – still prevalent today – that 'art' should be inherently non-instrumentalist is part of a long hangover from nineteenth-century aestheticism, and merely one form of poetics among many. It is impossible to predict, of course, what practical effect giving Falling and Flying to a gerontologist or a nursing student would have, but anything designed to help health professionals see clients or patients as complex human subjects (or, indeed, to help medical professionals recognise the diversity of 'the human') cannot be a bad thing.

Given the complexity of their theme (when does one become old? why does senescence occur? how do generations interrelate?), the editors helpfully organise their anthology thematically, from works about the processes of ageing, to portraits of ageing parents, elegies, and other forms of 'memory work' (including nostalgia). The anthology ends not with death, but with poems on 'Love and Joy in Advancing Age', which provide a hopeful change in tone, allowing the anthology to end on a vision of life-affirming sexuality and positive change.

Falling and Flying is indeed dominated by poets of the baby boomer generation, such as Kevin Brophy (whose 'The Sublime' is a standout poem in the collection), Dorothy Porter, and Diane Fahey, but there are younger poets too (such as Sarah Holland-Batt), while the inclusion of older writers, such as Chris Wallace-Crabbe and Jennifer Strauss, and late poets such as Rosemary Dobson and Gwen Harwood, shows that the interwar generation has or had much to say on the subject. The poems by Wallace-Crabbe, Strauss, and Dobson are key works in the collection, and a reminder that to age is to survive those who predecease us. Asking where the dead have gone, Wallace-Crabbe's 'There' answers that they are 'Somewhere ahead of us / in a meadow like the square root of minus one – / infinite pastoral, pure interstice – / where two objects can browse in the same point.' Strauss, in 'Tending the Graves', memorably images the dead as occupying a realm that is radically negative: 'They are so engrossed by death they refuse even to haunt us.'

Judith Beveridge

Judith Beveridge

While Falling and Flying is largely elegiac, the collection shows an impressive range of tones, styles, and forms. Interestingly, and perhaps coincidentally, the poems on happiness seem to attract the greatest range of registers, from the notably abstract (such as Charlotte Clutterbuck's use of mathematical language in 'Tricky Arithmetic') to the apparently relaxed and demotic. The latter is seen in Geoffrey Lehmann's 'Self-Portrait at 62', one of my favourite poems in the collection. But range can be seen throughout the anthology in individual poems such as Bronwyn Lea's 'Women of a Certain Age' (which illustrates Lea's mastery over tonal nuance); Paul Kane's powerful elegy 'For My Father Dying'; Andy Kissane's 'Visiting Melbourne' (which shows that affect and formal ingenuity are not incommensurate); and Adam Aitken's 'Notre Dame de Rouvière' ('Now life's your castle with one warm room'). Some of the poems don't light my fire (talking of warm rooms), but anthologies don't exist for one reader only.

In the light of this, it is perhaps egregious to complain about omissions, but a number did present themselves to me. The avowed wish to 'highlight doctor–poets' (such as Michelle Cahill, and Jennifer Harrison) makes the absence of Peter Goldsworthy, surely one of our best-known doctor–poets, a surprising omission. Tom Shapcott, who has written memorable poems on old age in recent years, is a similarly notable absence. Of course, one cannot be sure why individual poets are not included. Perhaps more striking is the lack of Aboriginal poets, especially given the importance of elders in indigenous cultures.

However elegiac and bleak Falling and Flying might sometimes be, it is ultimately a testament to the life-affirming elements of ageing and poetry. As Lehmann writes, 'Aged 62, I like what I do, / and remember an earlier body map.'

Ageing, as Beveridge and Ogle demonstrate, is marked not only by loss and fear, but also creativity, knowledge, ambivalence, and paradox. Becoming old can offer a new kind of appetite. As Vera Newsom writes, 'The young are too young to understand desire': 'Young we love, grasp, consume. Old, we savour. / And the taste sends us wild.'

Comments powered by CComment