- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Ian Dickson reviews 'James Merrill' by Langdon Hammer

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: James Merrill

- Book 1 Subtitle: Life and Art

- Book 1 Biblio: Knopf, US$40 hb, 944 pp, 9780375413339

James Merrill was the third child of Charles Merrill, co-founder of Merrill, Lynch & Co. and developer of the Safeway chain of stores, and the only child of Charles's second wife, Hellen. From his father he inherited his prodigious work ethic, his ambition, and his sex drive. Their relationship was a complex one. James had to fight his way out from under his father's immense shadow, while Charles, though not really understanding either his son's way of life or his writing, at least got to revel in James's increasing success and renown. In the end they achieved a wary mutual respect. In Sandover, James goes further and has his father declare from beyond the grave that '(h)e loved his wives, his other children, me'.

Merrill's relationship with his mother was more intimate and more fraught. Hellen Ingram Merrill was a southern belle with all the manipulative charm, bigotry, and desperate desire to keep up appearances that the stereotype entails. A major confrontation between them occurred when Merrill put her in the position of having to mix socially with an African American couple. Her pride in his literary success was tempered by her unease about his carnal life. As he puts it in an imaginary conversation with her: '(f)rom the age of nineteen I've been made to feel (first and foremost by you, dearest) my difference from the rest of the world, a difference laudable and literary at noon, shocking and sexual at midnight.'

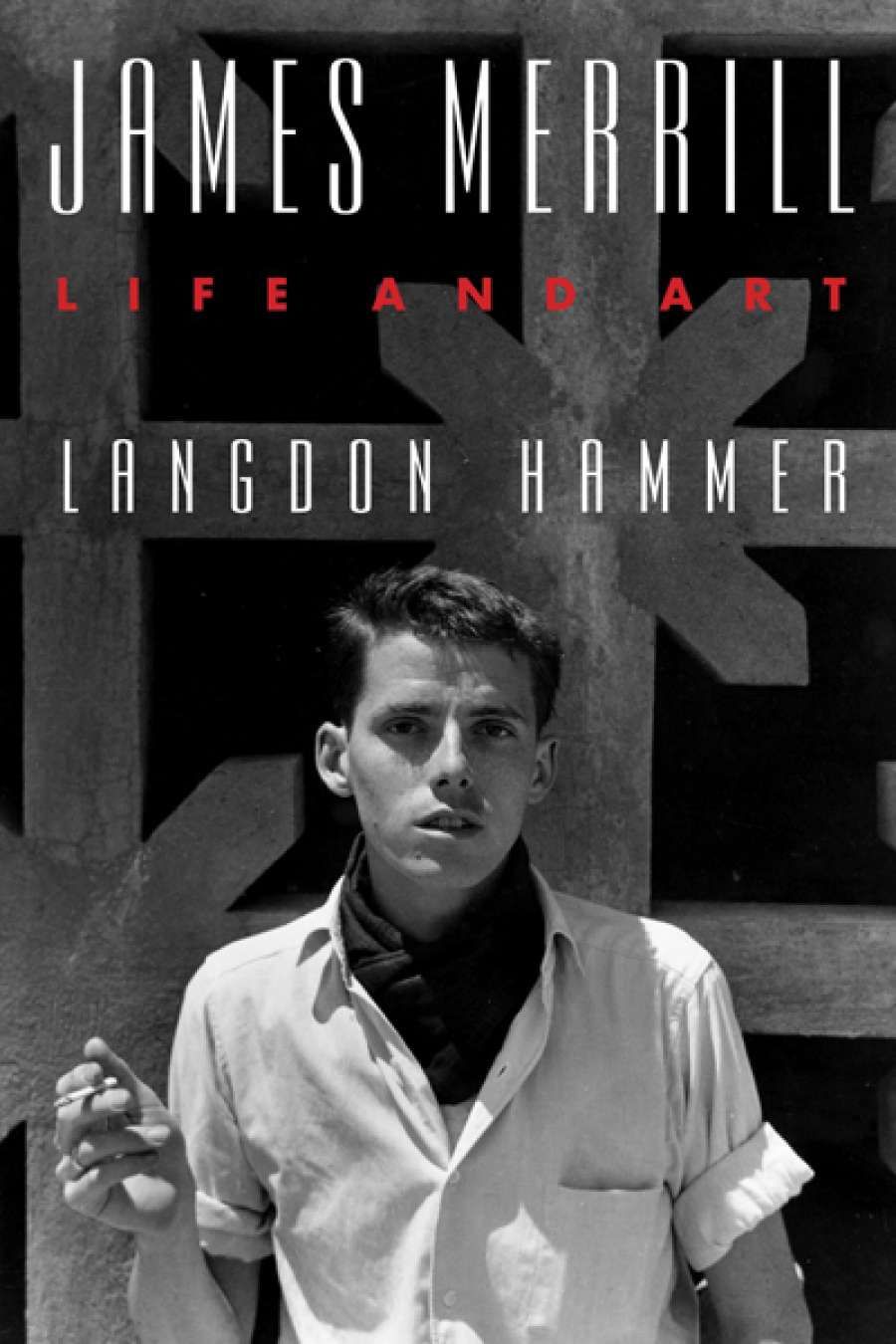

James Merrill (right)

James Merrill (right)

In his memoir, A Different Person (1993), Merrill describes how at the age of eleven his 'happy, sheltered' childhood ended when his father left his mother for another woman. In a time of emotional confusion, James was introduced to opera. He immediately responded to the lyric theatre's grandiose passions. When many other gay men of his generation spent their lonely adolescence at the movies yearning to become a Garbo, a Crawford, a Davis, Merrill spent his at the Metropolitan Opera House, thrilling to Brünnhilde's valour or the Marschallin's poised emotional resignation. Opera and the opera house recur throughout his work, sometimes as a metaphor for heaven, sometimes for hell.

Merrill made his break from what his nephew Robin described as 'the Southampton vacuity' by writing his bitter roman à clef, The Seraglio (1957), a devastating attack on his family and their way of living, in which his protagonist, Francis, literally castrates himself in order to remain acceptable to the world in which he was raised.

After a few years of drift and a series of brief, passionate affairs, Merrill met the handsome, affable would-be writer David Jackson. For the next thirty years they bought and renovated houses in Stonington Connecticut, Athens, and Key West, travelled the world, had extramarital affairs, and communed with the dead.

James Merrill and David Jackson, 1973 (Judith Moffett via Wikimedia Commons)

James Merrill and David Jackson, 1973 (Judith Moffett via Wikimedia Commons)

The elephant in the room mentioned earlier is of course the chronicle of their séances which became The Changing Light at Sandover. This vast tripartite poem has puzzled, irritated, and enthralled readers since the first section, The Book of Ephraim, was published as part of the collection Divine Comedies (1976). For some readers it evokes Milton, Blake, and Yeats, while others see it simply as an extravagant folie à deux. Hammer aptly describes it as a 'combination of Dantean seriousness and camp high spirits'. Through various spirit intermediaries, JM and DJ reconnect with dead friends, make new, usually famous, ones, and together with the spectral figures of W.H. Auden and their Greek friend Maria Mitsotaki discover an immense complex cosmology. In an early visit to Japan, Merrill had been deeply shaken by the Hiroshima Peace Museum, and much of the poem is concerned with the destruction mankind wreaks on the earth. As Hammer points out, one of the major themes of the work is in Merrill's words: '(h)ow to rid Earth for Heaven's sake of power / Without both turning to a funeral pyre.' Over the years, in many interviews both Merrill and Jackson were cagey when asked how real they considered the ghostly presences to be. Many of Merrill's friends and readers found it hard to connect the ironic, sceptical author of the lyrics with this monstrous, more than somewhat racist and élitist, spooky work. It must be said, though, that The Book of Ephraim contains some of Merrill's greatest poetry.

As they aged, the strain caused by Merrill's success and Jackson's lack of it pushed them apart, and Merrill found consolation with the much younger actor Peter Hooten, support that became more necessary as Merrill succumbed to HIV.

If Merrill's body was failing him, his talent certainly wasn't. 'Christmas Tree' is one of his last and most beautiful poems. Cut down and knowing it has only a short time to live, the tree relishes the care with which it is decorated and the joy it gives to the family who have received it:

Dusk room aglow

For the last time

With candlelight.

Faces love lit,

Gifts underfoot.

Still to be so poised, so

Receptive. Still to recall, to praise.

Merrill's life could be considered an aimless, self-indulgent saga were it not for the work that he fashioned from it, which gave it point and depth. Hammer states, 'for Merrill, truth's only touchstone was personal experience as sifted by sensibility and expressed in style'. His superb biography shows how the mundane constantly fed into the poems and was transfigured by them. A jigsaw puzzle, a record label, a jacket became the bases for the masterpieces 'Lost in Translation', 'The Victor Dog' and 'Self-Portrait in Tyvek ™ Windbreaker'. What in another biography might appear to be unnecessary details, here Hammer shows us the clay from which the poems are formed. His biography confounds the naysayers and cements Merrill's place at the forefront of American poets of the second half of the twentieth century.

Comments powered by CComment