- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Photography

- Custom Article Title: Helen Ennis reviews 'Lives of the Great Photographers' by Juliet Hacking

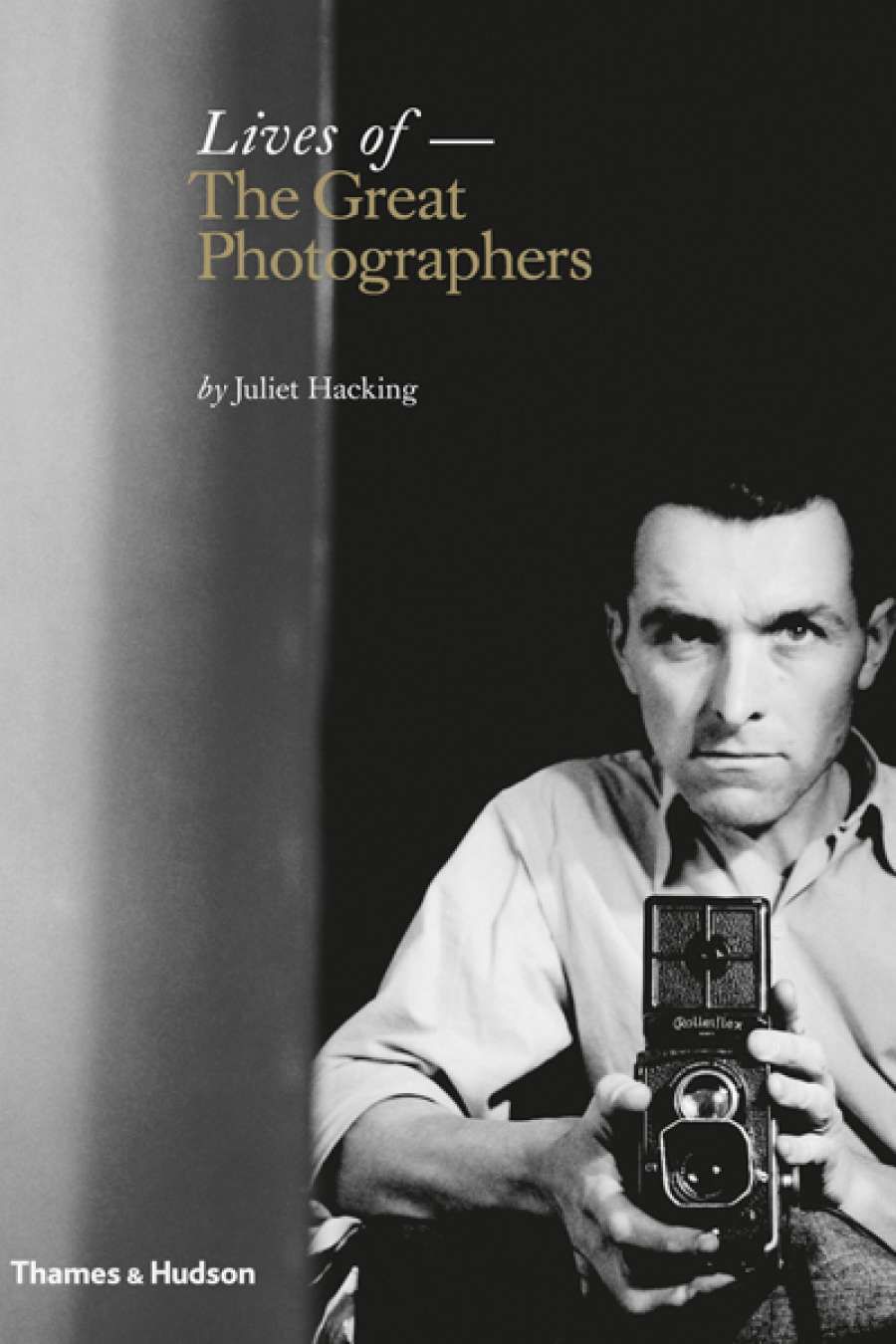

- Book 1 Title: Lives of the Great Photographers

- Book 1 Biblio: Thames & Hudson, $60 hb, 304 pp, 9780500544440

The essays on the thirty-eight photographers are very readable, but the ground covered is hardly original. Hacking isn't apologetic about choosing photographers from the last 180 years who have 'passed into posterity', or about confining the selection to the Western canon and, even more specifically, to 'an English-speaking photo-historical tradition that privileges England, France and the United States'. This narrow focus is at odds with a contemporary emphasis on developing world histories of photography that incorporate photographers from countries, for example in Asia, that have long been excluded from conventional historical accounts. The photographers Hacking selected hail from the heroic years of photography – mainly nineteenth-century pioneers and twentieth-century modernists. There is only a brief nod to the latter half of the twentieth century, with Arbus, Mapplethorpe, and Roy DeCarava being the most recent protagonists. Eight women's lives are represented, Madame Yevonde being probably the least well known. While the goal has clearly been even-handedness, with attention to nationality, gender, period, and so on, it is undermined by Hacking's decision to omit some photographers on the basis that they are currently receiving serious attention elsewhere. This assumes that readers know who these photographers might be and have access to the new material on them.

Oscar Graubner, Margaret Bourke-White atop the Chrysler Building, New York, 1934

Oscar Graubner, Margaret Bourke-White atop the Chrysler Building, New York, 1934

In the essays, each a few pages long, Hacking provides an abbreviated life story. She pays particular attention to the photographer's family background, education and training, political views and professional and commercial activities. Sometimes she elaborates on the secondary biographical literature and shifts in perspective that have arisen over time. This is useful in the case of the much-written-about Arbus; Hacking introduces more context and argues that the focus on psychobiography is limiting as Arbus's work can be productively related to the New Journalism of the period which dealt with the less palatable aspects of modern American life.

Some essays are flat, and their subjects remain one-dimensional; Henri Cartier-Bresson and August Sander are among those who don't come to life. Others offer snippets that beg for more elaboration; we are told, for example, that there is little available on Irving Penn's life, but not why this is so. Other photographers do rise from the page due to the inclusion of revealing details about character and temperament and the offering of interesting psychological insights. Ansel Adams was an only child motivated, Hacking suggests, by a desire to please his parents, while Julia Margaret Cameron was overly eager to make herself useful in order to secure access to her most famous sitters. In general terms, it is the lives of women that Hacking writes about most effectively.

As one might expect regarding the lives of creative individuals, there are some highly entertaining facts and anecdotes, but they are unlikely to expand our understanding of the photographs themselves. Arbus, who came from a privileged background, was tutored by a French governess in her early years; the adventurous Bourke-White supposedly kept two alligators on the terrace of her studio; Bill Brandt favoured ménages à trois in his domestic arrangements; Richard Avedon was jailed for civil disobedience after being arrested during a demonstration against the Vietnam War. The account of Walker Evans is especially lively because it is seemingly at odds with the tenor of his classical photographic vocabulary; he was an inveterate womaniser and drinker who famously stated: 'I've never been faithful to anything but my negatives.'

Lives of the Great Photographers is a beautifully produced book, well designed and with perfect proportions. The selection of photographs is excellent, both in relation to the biographical and autobiographical portraiture and the examples chosen to represent each photographer's oeuvre. The latter selection is on the light side – generally only one or two per photographer – but the book's attractiveness and readability are such that further investigation into photographers and photography is likely to be piqued.

Comments powered by CComment