- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Kerryn Goldsworthy reviews 'Mick' by Suzanne Falkiner

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Mick

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Life of Randolph Stow

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $50 hb, 896 pp, 9781742586601

But more complex matters intrude and persist, most vexingly the constant temptation to review the subject and not the book. And what exacerbates this problem here is Falkiner's own quietude and restraint, as though she had absorbed these qualities – life-ideals of Stow's own – by some indirect process of osmosis. She offers a massive amount of direct quotation – from novels, poems, diaries, notes, and letters to and from dozens of Stow's family members, friends, editors, publishers, literary critics, public records, and acquaintances from Stow's working life, and then leaves the reader alone with it. The overriding virtue of this book is Falkiner's steady trust in the intelligence of her readers. She spells very little out, presenting us instead with this carefully curated wealth of textual evidence.

There is consideration and mannerliness in this, towards her subject as much as towards her readers; she keeps impertinent speculation about Stow's spiritual life, his emotional life, and his sexuality to a minimum, quietly setting down such evidence as exists in his own words and in those of the people who knew him best. For a biographer, Falkiner has great consideration for other people's privacy, and the toggling between disclosure and respect is a delicate balance that she maintains throughout the book. An astonishing amount of patient mosaic work and attention to detail has gone into the selection and arrangement of these sources in order to produce a clear, if dauntingly detailed, chronological account of Stow's life. Falkiner's style is literate but lucid, low-key and unassuming. As a compellingly readable feat of painstaking Australian literary scholarship, this book should take its place alongside David Marr's Patrick White: A Life (1991), Hazel Rowley's Christina Stead: A Biography (1993), and Nadia Wheatley's The Life and Myth of Charmian Clift (2001).

Stow's own carefully guarded sense of privacy is evoked by Falkiner in a number of ways, often through her careful choice of quotation. A friend of his youth, the painter Patrick Maxwell, recalls that

I always had the feeling that he lived in a huge subterranean world, rich in treasure into which others were not invited. He came out often – bearing gifts or maps and postcards, stories and fables – but that world was too precious and vulnerable to admit others. He kept it a deliberate mystery.

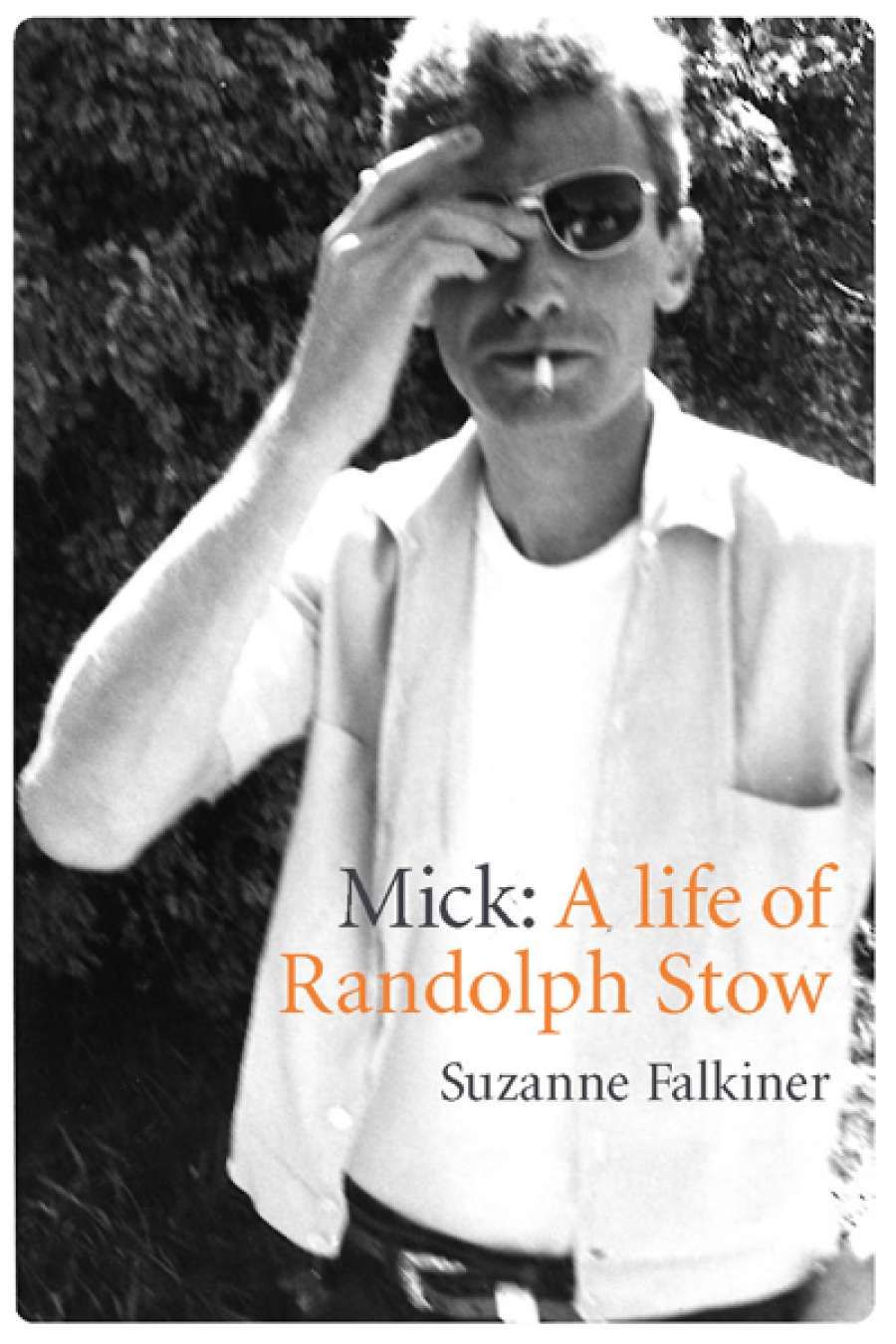

The mystery seems to extend even to his appearance, which was striking but elusive: slight and dark, with eyes almost alarming in their blueness yet remembered by one friend as 'almost silver'. In the evocative and mysterious cover photograph, Stow's eyes are entirely hidden by his sunglasses; the two painted portraits that appear in the book's illustrations seem to be making an actual feature of facelessness. One of the clearest pictures of Stow's physical appearance is provided by a characteristically vivid and forthright account from the poet and playwright Dorothy Hewett, remembering Stow as he was in his late twenties, at literary gatherings in Perth: 'He had this beautiful face and he was very stylish. I remember him turning up once at a party wearing knee-high leather boots – unheard of in those days. He looked fabulous. He never said anything. Just stood around and pissed off.' Even here – beautiful face and fairy-tale boots notwithstanding – the punchline about Stow is that he said nothing, and then disappeared.

The sense of a solid core of self is likewise absent from the history of his name: christened Julian Randolph Stow, he was almost immediately nicknamed 'Micky', subsequently shortened to 'Mick'. Although his mother was still referring to him as 'Julian' in letters to the headmaster of his private school in Perth, he seems to have been Mick to almost everyone from infancy, except when the locals, in the English towns that he made his home in the second half of his life, retroactivated 'Mick' to 'Michael' and called him that.

Portrait of Randolph Stow, Essex, U.K., 1985, by Alec Bolton (National Library of Australia)

Portrait of Randolph Stow, Essex, U.K., 1985, by Alec Bolton (National Library of Australia)

Falkiner leaves the complex matter of Stow's sexual life for a friend of his to sum up: 'I suspect he didn't feel comfortable with his own sexuality entirely. I think there was some torment going on there, particularly with his family, and that made him the writer he was, and the person he was.' Not entirely clear about his own sexual orientation when young, Stow claimed later and bitterly that 'Gossip made me a homosexual before I was one.' Although it's clear that he was usually sexually active, Falkiner, with characteristic restraint, recounts only one such experience in any detail, and there, as elsewhere, she leaves it to Stow to recall: a happy interlude in his late twenties, while living in Scotland, with the frank, witty, and charismatic Australian writer Russell Braddon. 'After Braddon's arrival in Scourie, Mick confided exuberantly ... they hadn't got out of bed for five days.'

This story of his life begins slowly; as Falkiner goes up through the narrative gears, there is a lot about Stow's parents and their antecedents. Even by page seventy we are still not quite to the end of his schooldays, and our eyes are a little glazed from report cards. But there is more to this than simple, grinding reportage, for Stow's intellectual precocity and lifelong interest in genealogy were two of the defining influences of his life, and it is absolutely worth a biographer's while to look closely at the roots of both.

Between mid-April 1958 and mid-November 1959, a couple of weeks short of his twenty-fourth birthday, the following things happened – in chronological order – to Stow. In April 1958, he was awarded the Australian Literature Society's Gold Medal for his first collection of poems, Act One: Poems (1957). In September he survived, by chance, a serious attempt at suicide. In April 1959, he won the Miles Franklin Literary Award for his third published novel, To The Islands (1958). In May he arrived, as a Cadet Patrol Officer, in the Trobriand Islands. In August he received the news that his father had died back in Geraldton. And in November 1959, in a state of physical debility and psychological turmoil – overdetermined in both aspects – he made another suicide attempt, again serious, and again survived by chance.

Stow was repatriated to Australia to recover, and spent the next few years in adventurous travel, but eventually settled down in the south-east of England from where his Stow ancestors had come. For ever after, he saw this moment of breakdown as the turning point in his life and work. Of his eight novels for adults, the one that followed his breakdown was the heavily autobiographical The Merry-Go-Round in the Sea (1965) – Stow had published five literary novels before his thirtieth birthday – and then the twinned or companion narratives Visitants (1979) and The Girl Green as Elderflower (1980), which explore different aspects of his breakdown and recovery by translating them into narratives with a far greater breadth of reference than the circumstances of his own life.

The diagnosis of clinical depression comes as no surprise, especially as his father was almost certainly a fellow-sufferer, and Stow's descriptions of it will resonate with anyone who knows the condition: 'I don't know where the misery comes from. Blackness falls from the air. It's like that,' he wrote to Bill Grono; and, elsewhere and shatteringly, 'that planet (ah, Christ) of black ice'.

Scholars in the field of Australian literary studies have kept Stow's reputation alive. As his biographer, Falkiner chooses to leave the literary analysis to others, giving details about the production of Stow's writing as it reflected his daily life, and relating the writing to the life only where it seems appropriate. But occasionally she will simply offer a poem or a passage of prose to the reader as a window onto Stow's mind, as with the end of the chapter that deals with Stow's breakdown in 1959. 'Stow's own account of events is best conveyed in his poem "Kàpisím! O Kiriwina",' she writes, ending the chapter with the poem.

As in so many other places, Falkiner trusts her readers to think and feel for themselves, and one line in particular from this poem tells alert readers everything they need to know about that moment: 'The sudden storm drove my boat from all known islands.' But fortunately, an image from his old age in the port of Harwich provides a kind of balancing moment for this desolation: a fragile old man feeding the swans. 'When he appeared on the sea-wall they would swim towards him, and at low tide they came from the water to eat from his hands.'

Comments powered by CComment