- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Media

- Custom Article Title: Susan Sheridan reviews 'Australian Women War Reporters' by Jeannine Baker

- Book 1 Title: Australian Women War Reporters

- Book 1 Subtitle: Boer War to Vietnam

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $39.99 pb, 269 pp, 9781742234519

Such critical reportage rarely emerged from the battlefields of the Great War in Europe. Sydney journalist Louise Mack, for example, wrote sensationalist stories for Lord Northcliffe's London papers about her experiences in Antwerp in 1914, where she claimed to have escaped the Germans by disguising herself first as a mute hotel maid and then as a peasant woman.

By the start of World War II, there were more women journalists in the profession, many like Connie Robertson of the Sydney Morning Herald and Iris Dexter of Woman magazine eager to escape confinement to the women's pages and to report on the war. But even if their editors agreed to send them abroad, the Department of Information, responsible for both war correspondents and publicity censorship, was hostile to women journalists. In 1942, accreditation for women correspondents was instituted, but they were only permitted to report on the women's auxiliary services within Australia.

The old story – lack of suitable 'facilities' (toilets and showers) – was the usual reason given for refusing women journalists, and even official war artists like Nora Heysen, access to operational areas. While officials of both the British and Australian forces stood firm against an invasion of women correspondents, the Americans were more accommodating. Lorraine Stumm, an enterprising Australian who had worked for the Daily Mirror in London, successfully offered her services to become the only woman war correspondent working from General Douglas MacArthur's Brisbane office. But the Australian authorities refused her permission to go to Darwin to report on the British Spitfire pilots there because 'it would be impossible for her to share the male correspondents' mess'; and they were outraged when MacArthur allowed her to accompany male correspondents to New Guinea, where she was quartered with the nurses.

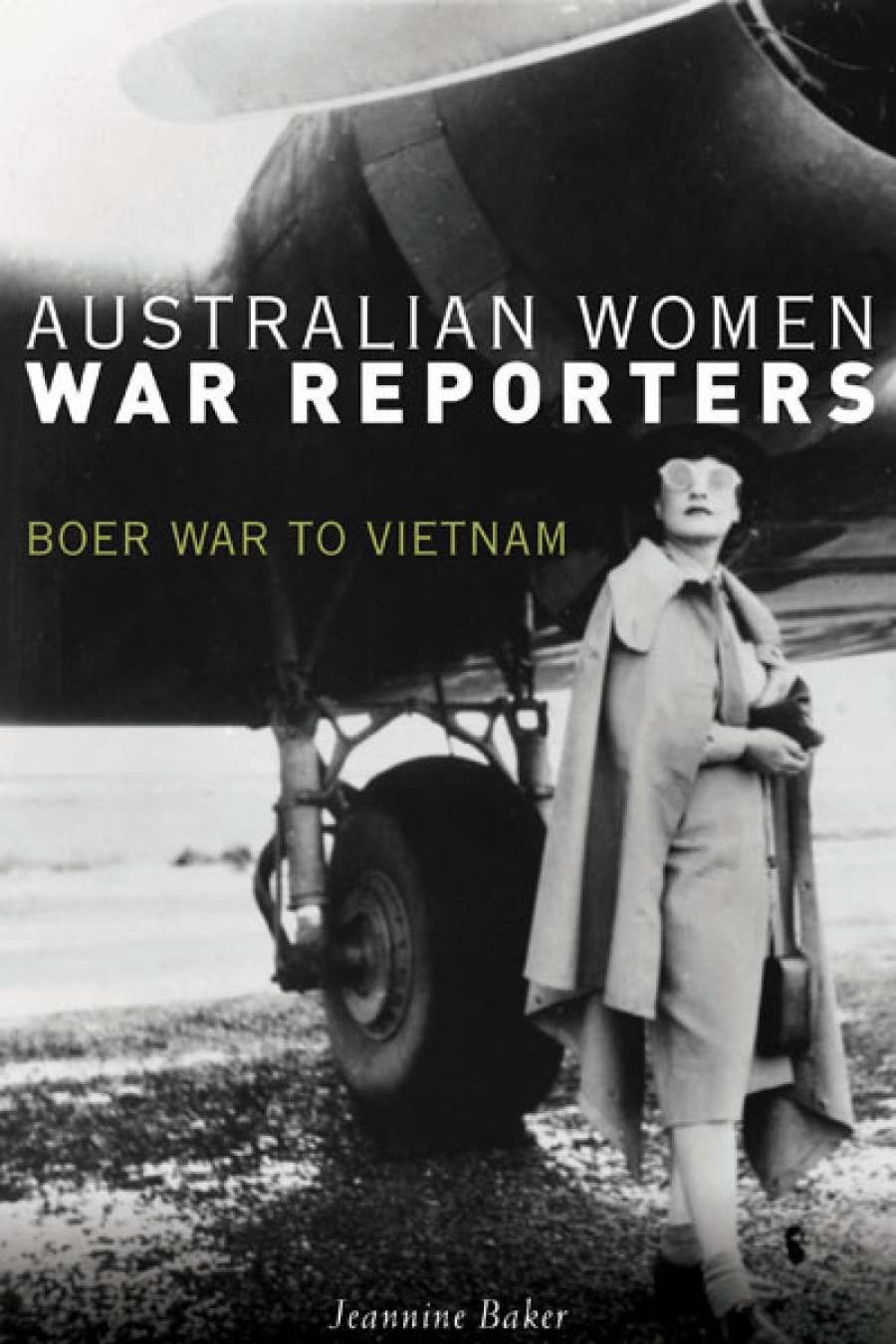

Journalist Iris Dexter standing beneath the starboard engine of a Douglas C-47 aircraft, during the War Correspondents' Tour, 1943 (photograph by Barbara Joan Isaacson)

Journalist Iris Dexter standing beneath the starboard engine of a Douglas C-47 aircraft, during the War Correspondents' Tour, 1943 (photograph by Barbara Joan Isaacson)

The US army was generally more willing to consider equality of treatment of men and women reporters, and indeed when the United States entered the war in Europe equality of treatment for women was written into the regulations. From early in the war, Australians Margaret Gilruth, Elizabeth Riddell (writing for the Sydney Daily Mirror), and Anne Matheson (Australian Women's Weekly) had covered the British home front, filing stories about evacuation, rationing, immigration, and bomb shelters, clashing with the censors on occasion when they wanted to write of the 'war-weariness' of Londoners. When later they were able to gain accreditation with US forces their range was vastly expanded. Matheson, for example, covered the aftermath of D-Day and flew with the US Ninth Airborne squadron as they crossed the Rhine. She reported from the destroyed cities of Cologne and Nuremburg and from the Buchenwald concentration camp.

'Baker presents a gallery of impressive women who reported war news despite the obstacles put in their way by military authorities and press traditions alike'

The end of the Pacific War in August 1945 meant that war correspondents became foreign correspondents, yet while they were less controlled by military authorities the women among them were still subject to the belief that they should keep to the domestic margins, as was seen in Dorothy Drain's stories for the Women's Weekly in 1946 on the Allied Occupation of Japan. Yet in her later chapters Baker develops the crucial argument that ideas about how to report war changed radically. Since the end of World War II it was no longer considered to be only the 'woman's angle' to focus on people's experience, especially the experience of civilians who suffer.

The final chapter, 'Cold War Conflicts ... And Beyond', charts many changes in war and war reporting, and features many women whose names are familiar to us today: Monica Attard, Ginny Stein, Sally Sara. In these more recent conflicts the foreign correspondent becomes, of necessity, a war reporter, like Attard in Russia during the breakup of the Soviet Union, reporting on civil wars in the republics. In these circumstances, journalists are no longer protected but may be targeted as combatants; as well, there are the untold stories of sexual assault – untold because the women know they will be seen as vulnerable, and discriminated against. And it is now recognised that war reporters can suffer, men and women both, from post-traumatic stress disorder: Sally Sara's experience of this condition on her return from Afghanistan convinced her that it resulted from bearing witness to scenes that were 'not just physically confronting [but] morally wrong'.

Comments powered by CComment