- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

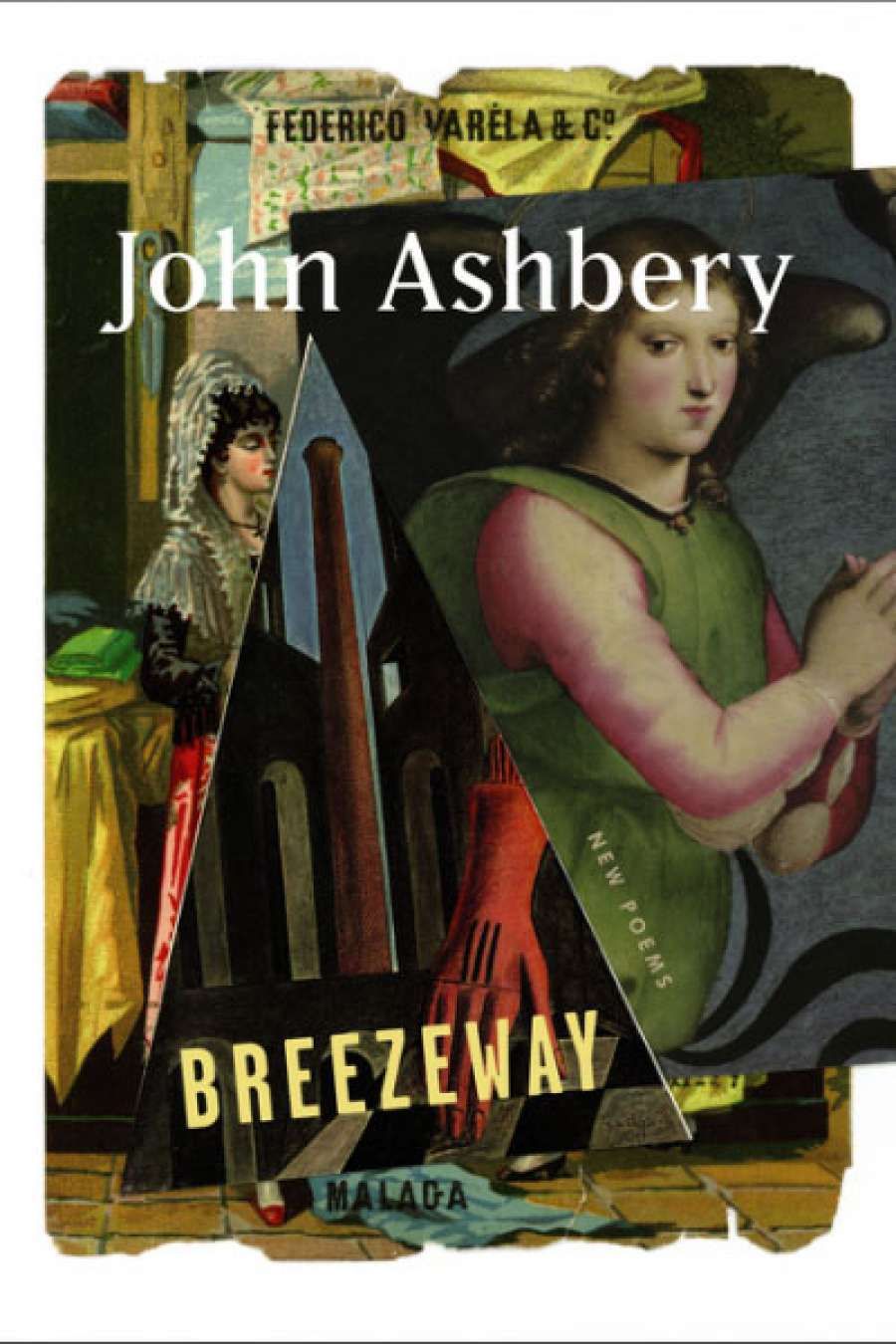

- Custom Article Title: Gig Ryan reviews 'Breezeway' by John Ashbery

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Breezeway

- Book 1 Biblio: Carcanet Press, $22.95 pb, 121 pp, 9781784101152

Given Ashbery's hundreds of expansive poems written over sixty years, it is instructive to note that along with Rimbaud, Whitman, Stevens, Stein, Auden, Eliot, Moore, Bishop, and the less obvious Thomas Lovell Beddoes and John Wheelwright, Ashbery (born in 1927) was much influenced by the novels of Proust and his contemporary Raymond Roussel, as well as by de Chirico's little-known novel, Hebdomeros (1929), all written in protracted, clause-layered sentences. Ashbery has also recently published an acclaimed translation of Rimbaud's Illuminations (2013), Collected French Translations: Prose (2014), and Collected French Translations: Poetry (2015).

Breezeway maintains humour with titles such as 'The Goofiad', but there is occasional pessimism among its slithering moods. While his last book, Quick Question (2013), partly appraised his lifetime achievements, here voices interrupt and question as ever, but there is a gnawing bleakness in these new contemplations of mortality.

We have to live out our precise experimentation.

Otherwise there's no dying for anybody,

no crisp rewards.

('Breezeway')

O higher than the grave,

always aware, under the occasion,

what kind of peace I don't know.

We're not gonna be here anymore.

It may not be the same thing: ghost-published.

Liquidational. Then I wrote my Minuet in G.

Help you guys. The kind of messages we read

on the surfaces of certain clouds.

('Leaf, Resting')

'Traversing art, music, history, television, Ashbery reinvents consciousness in the late twentieth century'

These short poems are no less various than earlier works that derange and delight ('You found yourself / inside a huge pen / or panopticon', Flow Chart, 1991), but these poems imagine decline and departure, referring to doctors, hospitals, patients ('When do they turn them over?', 'Thereat'), medical treatments ('A mouse can show what works / even if no one knows why, he said.', 'East February'), as well as nostalgia in the recurring 'foxtrot'. It is now usual to see Ashbery's work as self-referential, with Shadow Train (1981), for example, depicting and resisting his disciples, but all poetry is self-referential in that its practice enunciates and elucidates itself, just as it assaults yet contains previous poetry. Ashbery discomposes the contemporary (Hillary Clinton's listening tour; online 'likes') into poems that sleekly glide and yet bamboozle, creating the 'pleasant surprise' he modestly describes as his intention (Paris Review, 1983), hence his amused deployment of new clichés – 'Own the blankness ... The place was above all creative' ('Heading Out'). Sleep and waking recur, echoing Shakespeare's The Tempest ('that when I waked / I cried to dream again'), as well as Keats. The last poem, 'A Sweet Disorder', takes its title from Robert Herrick and reprises Keats: 'Pardon my past, because, you know, / it was like all one piece. / It can't have escaped your escaped your attention / that I would argue. / How was it supposed to look? / Do I wake or sleep?'

Poetry is the mind alert, the poet's yearning libation. That Ashbery includes the Kardashians ('Exeunt the Kardashians', 'Seven-Year-Old Auroch Likes This') is no more surprising than John Donne's mention of the recently 'discovered' Peru. Art tracks the age it inhabits, while transforming it. Ashbery once wrote of Gertrude Stein in Poetry Magazine: '[Stein] attempts ... to create a counterfeit of reality more real than reality. And if, on laying the book aside, we feel that it is still impossible to accomplish the impossible, we are also left with the conviction that it is the only thing worth trying to do.' To encase Ashbery in any definitive 'school' is like hammering constellations into place.

Comments powered by CComment