- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

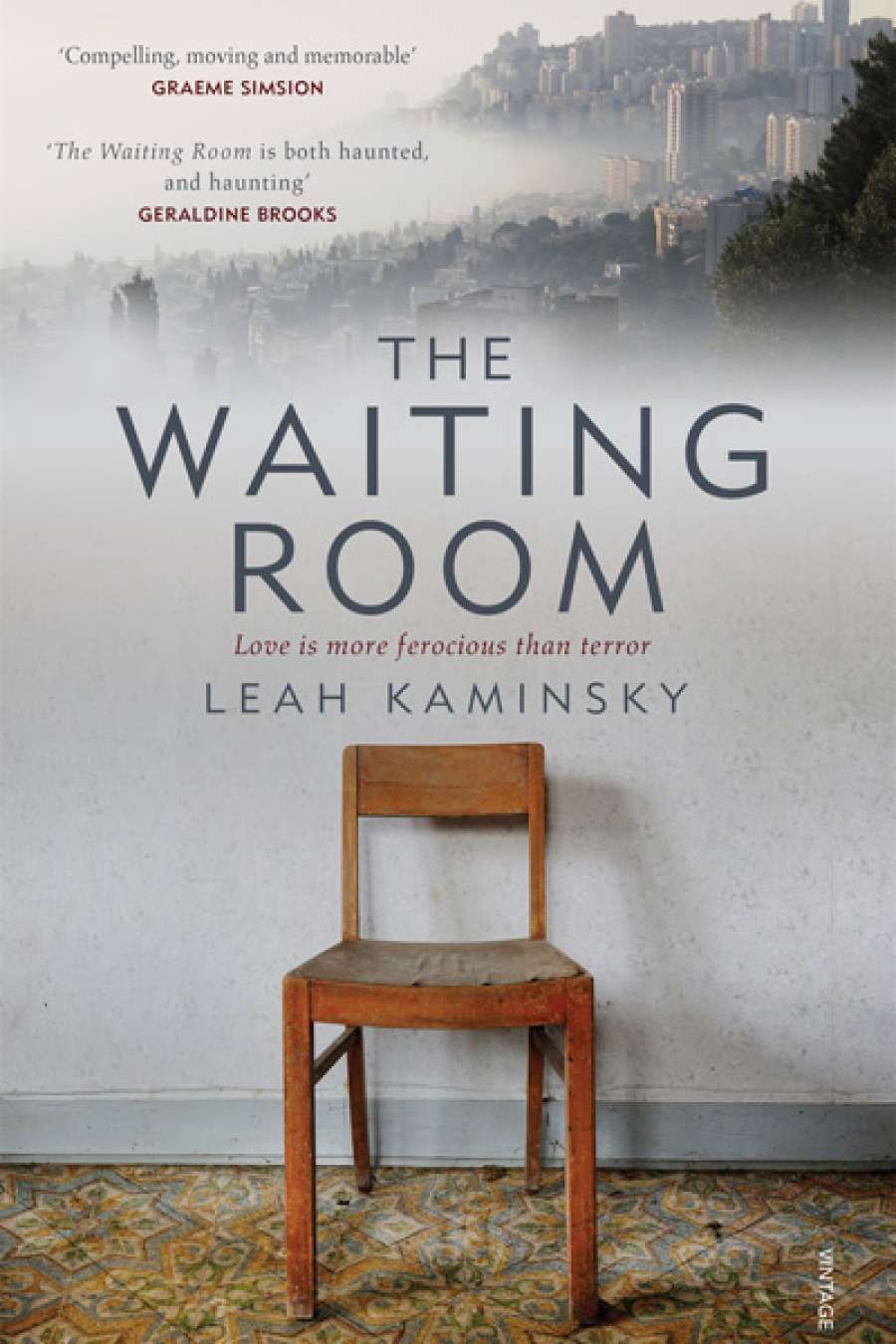

- Custom Article Title: Naama Amram reviews 'The Waiting Room' by Leah Kaminsky

- Book 1 Title: The Waiting Room

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $32.99 pb, 304 pp, 9780857986221

Kaminsky's well-drawn central character is an Australian family doctor living in Israel's port city of Haifa with her husband, Eitan, and their six-year-old son, Shlomi. The daughter of Holocaust survivors, Dina had grown up in Caulfield, a Jewish enclave of Melbourne, in the shadow of her parents' trauma, among whispers of concentration camps and round-ups, torture, and death. Though she has built herself a new life and family, Dina is besieged by the burden of the past and the uncertainty of the future. Living in a country where terror threats are announced as casually as the weather, Dina, pregnant with her second child, faces a dilemma: stay with her husband in Israel – where she is seen as an Aussie galutnik 'Diaspora Jew', never fully accepted as a 'true Israeli' – or walk away from their fraying marriage and return to the safe, quiet shores of Australia?

Dina's two worlds – that of her parents' horrific past and that of her demanding present – are inseparable in the narrative as Kaminsky deftly explores the mechanisms of remembering as well as remembrance. Set in 2001, the story opens with the gruesome scene of a bombing and retraces the morning leading up to it. Dina's actions on one fateful day are interspersed with her thoughts, flashbacks, nightmares, and conversations with the persistent ghost of her mother, a survivor of Bergen-Belsen. Following Dina with a perpetual cigarette in her hand and the haunting mantra that 'nowhere is safe', the mother's ghost carries much of the story's emotional weight. Under her gaze, Dina's world becomes claustrophobic, suffocating, encircled by the eyes of the restless dead. Though Dina is a doctor, she is, in some ways, the patient – reluctantly waiting. She is always rushing – away from something? Towards something? A shoemaker at the shuk tells her, 'A woman with child should not rush.' A baker tells her 'you can't rush your future'.

'Kaminsky ... displays superb descriptive skill, with scenes and portraits that are sharply observed, well-researched, and vividly evoked'

Kaminsky, also a writer of short fiction, poetry, and creative non-fiction, displays superb descriptive skill, with scenes and portraits that are sharply observed, well-researched, and vividly evoked. She convincingly captures details of language and culture – Eitan tongue-clicking to mean 'no thanks', a baker gathering the fingers and thumb together 'like the petals of a tulip' to mean 'wait', a reverse-latte coffee style called 'upside down' – that give a uniquely Israeli flavour to the telling. And yet Dina lives her life 'neither here, nor there', staring at the bulbul birds and woodpeckers among carob and pine trees while a part of her 'is looking out onto magpies and lorikeets sitting high up in the old wattle tree back home'.

Leah Kaminsky

Leah Kaminsky

Kaminsky represents the diversity of Haifa through a multicultural cast of patients that fill Dr Dina Ronen's waiting room. Mrs Susskind is Dina's European-Jewish neighbour, a disturbed elderly woman who spouts abuse at everyone, not least her Filipina carer and a Muslim tradesman. Soussane is a Christian Arab woman praying to have a son to redeem herself in the eyes of her husband. Gentle Tahirih is a Baha'i widow who had fled horrific persecution in Iran. Evgeni is a Jewish Russian migrant who, despite his education as a ship engineer, now sweeps the streets of Haifa. Dina counters her patients' misery by offering compassion (Latin for to suffer with) in a generous spirit, to the point of 'compassion fatigue'. Yet she, too, is not immune to the deep fears that feed prejudice, and later finds herself ashamed of having accused an innocent man of terrorism.

Though the novel could be dissected in political terms, its project is personal, as a work that seeks to understand the self. But, of course, the personal is political, and readers' own views of the region's conflict will shape the way in which they receive the book. At a time when the world is facing waves of refugees escaping persecution, this powerful study of the terrible legacy of trauma is a reminder that we must stand up against prejudice in all its forms.

Can compassion transcend one's deepest-rooted fears? Can one live with the past without sacrificing the future? Vulnerable and uncertain, can one find the strength to endure, to wait?

'Ask the patient,' my grandmother would say.

Comments powered by CComment